Orwell and the Refugees

Meet the Living History Near You

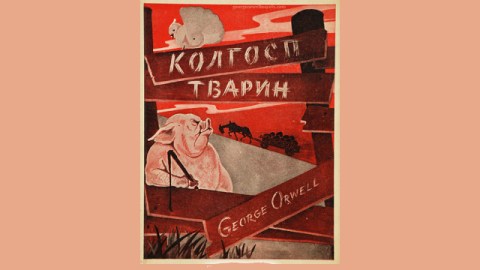

After toiling over researching and writing a screenplay about George Orwell struggling to publish Animal Farm, I was stunned to discover a first edition of Orwell’s masterpiece in my family. Not just any first edition—this book was printed and distributed in Ukrainian by refugees right after World War II, with Orwell’s help. But the most eye-opening discovery for me was that for an entire summer, I lived near Ihor Ševčenko, the political immigrant who, as a young man, masterminded this rare refugee camp edition.

I was a student at the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, which he had co-founded, and remember his white bowl-haircut—like something out of Monty Python and the Holy Grail, his long nose, dark-framed glasses, and his slightly amused expression. To me, he was just another stately professor, and I was more interested in planning my indefinite move to Ukraine to research a screenplay. But that’s the thing about being “straight out of college”—you become obsessed with that “next step.” The man who could have told me everything I needed to know was already right there. And from what I’ve gathered from talking to a few people who knew him best, I missed out on knowing an alien vacationing from another planet.

“He did not belong to this world,” Olga Strakhov, a best friend of “this beautiful mind” told me over lunch in Cambridge. “He spoke ten languages like a native…he was greedy for life.”

Ten languages? I asked Strakhov for a list, just to process this feat. Ševčenko spoke English, German, French, Italian, Modern Greek, Ukrainian, Russian, Polish, Czech, and Turkish like a native, and had perfect reading knowledge of the dead languages Latin, ancient and byzantine Greek, and Old Church Slavonic. Strakhov told me that in his final months, before he passed away in December 2009, at the age of 87, Ševčenko forgot a few basic skills—like how to use the telephone, but his mind retained its masterful fluency of these languages.

In Why Orwell Matters, Christopher Hitchens devotes only a few paragraphs to telling the story of how Ševčenko, then a young refugee, twenty-four-years-old, had attained a copy of Animal Farm, and wrote to Orwell in London, asking authorization to publish a Ukrainian translation of his book: “For several occasions I translated different parts of ‘Animal Farm’ ex abrupto. Soviet refugees were my listeners. The effect was striking. They approved of almost all of your interpretations. They were profoundly affected by such scenes as that of animals singing ‘Beasts of England’ on the hill.” [Ševčenko had learned English by listening to the BBC.]

Ševčenko: Not Your Average Ukrainian Refugee

Ševčenko was not a typical Ukrainian refugee. The people confined to the refugee camps were traumatized masses that included Holocaust survivors, prisoners of war, and forced laborers. Born and raised in Poland by exiled Ukrainian nationalists, Ševčenko spent the war in Prague learning German and Czech while getting his first PhD. There, he married his first wife, Oksana, a Soviet refugee and the daughter of Myxajlo Draj-Kmara, a celebrated Ukrainian poet killed during Stalin’s purges. Ševčenko’s own parents had been leaders fighting against the Bolsheviks for Ukraine’s independence during the Russian Revolution. His love for his country of origin shaped his career. His greatest fame was due to his stunning “detective” work as a renowned scholar, drawing attention to the neglected Kievan Rus—Ukraine’s medieval Viking kingdom. His academic globe-trotting was the stuff of an adventure novel.

Initially, I was curious to know how Ševčenko had gotten in touch with Orwell. Was it just that easy? If he was a refugee stuck in postwar Germany, how did he hear about a book by a fringe writer in England? Joseph Stalin, one of the cruelest, most demonic leaders in world history, was then an Ally, and the Allies ran the refugee camps of occupied Germany and Austria; how did Ševčenko manage to publish an anti-Stalin satire there?

The questions I could have asked and attained colorful answers to during my summer at the Harvard Ukrainian Institute in 2005 nagged at me.

I was grateful to learn from reading Hitchens that Ševčenko printed a few thousand copies of his translation, and only around 2,000 copies were distributed to Ukrainian refugees; U.S. soldiers confiscated the rest and handed them over to Soviet authorities to be destroyed as propaganda. The preface Ševčenko had insisted Orwell write became his only published introduction to Animal Farm, and his most intimate discussion of the book. “It was of the utmost importance to me that people in western Europe should see the Soviet regime for what it really was,” wrote Orwell.

There wasn’t much my family could tell me, either, about how this rare Ukrainian edition came to be. In 1947, Ševčenko couldn’t have known that he was making literary history, and my uncle couldn’t have known that Kolhosp Tvaryn—Ševčenko’s Animal Farm—would one day be a valuable collector’s item. After escaping the Soviet Union through the hell of the Eastern Front, both sides of my family lived in refugee camps in postwar Germany, or displaced persons (DP) camps, as they were called. My uncle, then a teenager, remembers picking up a copy of Orwell’s book in the canteen of his DP camp in Heidenau, after his teacher, in a school the Ukrainian refugees had organized themselves, insisted everyone read it. Orwell’s book was so meaningful for exposing Soviet evil that my uncle brought it with him when he immigrated to the United States, and he kept it on his library shelf, and decades later, gave it to me. Since he was a teenager when he obtained the book, he says that’s all he remembers.

Searching for the Missing Pieces, and a Time Machine

Luckily, Ševčenko’s close friends are as generous as he reputedly was, and shared some of their stories. Strakhov told me how, in 1945, Ševčenko had supported himself, his wife, and mother-in-law by creating a Ukrainian-English dictionary of a thousand words. He sold this pocket-sized dictionary to the Ukrainian DPs in exchange for cans of Spam they were given by relief organizations.

Soon after, he ran into an old friend who introduced him to an editor of a Polish newspaper that was hiring. Ševčenko’s job for the paper was to scour the British news. In doing so, he became a fan of a funny column in the leftist paper Tribune, called “As I Please,” written by Orwell.

Orwell was very much a blogger before bloggers; “As I Please” was him riffing on just about anything he pleased—from American fashion magazines to Scottish nationalism to venereal diseases. Ševčenko’s editor at the paper and his editor’s mother—an esteemed member of Polish intelligentsia—had both translated essays of Orwell’s for Polish journals, and had the writer’s address in London. Ševčenko, who had already started working on his translation of Animal Farm during his lunch hours and at night, sent Orwell a long heartfelt letter. In it, he explained in flowery English—impressive for picking up the language from the radio—that Soviet refugees were puzzled by the West’s friendly relationship with the Soviet Union and wondered if anyone in the West—to quote his letter—“’knew the truth.’” Ševčenko concluded: “Your book has solved that problem.”

Why Orwell and Ševčenko Matter

Orwell and Ševčenko were two pre-fame giants, and kindred spirits, who found each other at just the right time. After struggling for a year to find a publisher for Animal Farm, Orwell’s wife died in surgery, shortly after they’d adopted their infant son, Richard. Orwell was in declining health, a widower, and suddenly a single parent when Ševčenko’s letter arrived, asking to publish a book he had spent nearly a decade on that was deemed too radical to publish. (T.S. Eliot told him as much in a lecturing rejection letter on behalf of Faber & Faber.) Orwell’s book had given Ševčenko hope, and Ševčenko’s letter had given Orwell hope.

“I have been saying ever since 1945 that the DPs were a godsend opportunity for breaking down the wall between Russia and the West,” Orwell wrote, in 1947, to his friend Arthur Koestler, author of the Soviet dystopian novel Darkness at Noon. In the letter, he appealed to Koestler to give Ševčenko some of his books to translate into Ukrainian for the refugees.

Strakhov told me that Ševčenko didn’t stay in Munich for long; he attained a Polish officer’s uniform through a friend and wore it all the way to the safety of Belgium, undisturbed. At the Université Catholique de Louvain there, he earned a scholarship and started on the path to becoming a world-renowned scholar.

To those who knew Ševčenko, Orwell was just a footnote. His former research assistant, Byron MacDougall, now a Byzantium scholar himself, was almost headed into an insurance job after college when he signed up to work for Ševčenko instead. The post ended up including countless leisurely discussions and dinners together. Having been rejected the year before from graduate programs, he poured his heart out in his application to Brown University in a beautiful essay that begins, “My time with Professor Ševčenko has been the formative experience of my life,” and shares at the end a haunting sentiment, “I felt the new pain of not having known him as a young man.”

During their respective struggles in war ravaged Europe, Orwell and Ševčenko both had great odds against them. Yet they both did meticulous work as though writing for audiences in a just future.

Andrea Chalupa is the author of the 2012 e-book Orwell and the Refugees