How Faulty Risk Perception and Politics Put Us All At Risk

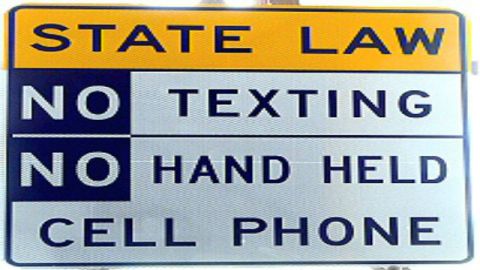

I had a conversation the other day with a friend, an elected official who represents my community’s interests in a legislative body. I called to offer some information that might help her consider proposed legislation to allow only hand-held cell phone use by drivers. Like most of you, I am certainly worried about the way cell phone use distracts drivers. But while that risk scares me, the conversation with my legislator scared me more.

I wanted my legislator to know that laws that allow only hands-free cell phones for drivers don’t work. After such laws took effect in four states, research showed that insurance claims for accidents either stayed the same or rose slightly. That’s right. In one jurisdiction, accidents ROSE!

Why might that be? Two reasons. First, the unique nature of a conversation on a cell phone demands much more mental attention, so more than 90% of the distraction from using a cell phone while you drive is mental, according to research at the University of Utah. Then there’s the psychology of how we perceive risk. When you think you have more control, you feel safer. Governments that ban motorists use of hand-held phones but allow hands-free devices are explicitly stating that hands-free is safer. So drivers using such devices think they’ve done something to reduce the risk…that they’re in more control, and safer…and they drive with less caution, even though their brain is just as addled. The hands-free law feels right, but by ignoring the evidence, it potentially RAISES the risk.

I wanted my legislator to know about that research, and to understand the way risk perception psychology plays a role in our behaviors, so that my area won’t adopt a law that at best won’t work and at worst might things a bit more dangerous. But the response I got was troubling, and far more threatening than the risk of cell phones and driving that I was originally calling about.

My legislator friend, a supporter of the hands-free law, listened carefully. She challenged my evidence, and questioned me carefully, thoughtfully. We had a good conversation, and in the end, she acknowledged there was merit to my case. She conceded that there are reasons to doubt whether a hands-free law would improve public safety. But she said she was still going to support it, despite the evidence, “Because that’s what people want.” THAT is scary!

Why? Isn’t that how things are supposed to work in a democracy? Our representatives are supposed to legislate based on what We The People want, right? Well, yes, and no. Our representatives have to be responsive, yes. Their choices must somehow reflect our feelings and values. But they also have to understand that the perception of risk is inherently emotional and instinctive, and that as a result We The People are sometimes more afraid than the evidence says we need to be, or not as afraid as the facts say we ought to be. That frequently produces public support for policies that protect us from what we’re afraid of more than from what threatens us the most. Sometimes it even produces support for policies that feel right, but actually make the risk worse, as might be the case with laws to allow only hands-free phones for drivers.

Policy makers have to recognize this risk, and do more than just blindly turn our gut fears into law. In the name of the public interest they supposedly serve, they have to be less emotional than we usually are about risk, more careful that their decisions aren’t just politically popular but also reflect fact-based analysis of what will do the public the most good. And they have to have the courage to make decisions that sometimes fly in the face of popular fears when our fears support policies that feel right, but actually raise our risk.

But there are two problems here. First, the same psychological risk perception factors that influence how scary things feel to you and me, impact politicians in the same way. They are, after all, people too. Whether we’re a citizen or a legislator, a law to put both our hands back on the wheel legitimately feels like it will reduce the risk of cell phone us be drivers, by giving us more control. Second, ‘courage’ is not a characteristic common to most politicians, whose jobs depend on giving people/voters what they want. It would take an uncommonly brave politician to tell voters that what they want may be bad for them, and that how they feel about a risk is wrong.

So my representative is about to act in a way that feels right to her personally, and in a way that is good for her job security, even though she knows it’s potentially harmful to public safety. And she’s not the only lawmaker who behaves this way. Most do. And cell phones and driving isn’t the only issue where this happens. This is the way laws are made about environmental issues, or health issues, or terrorism, or crime, or any issues that worry us enough to demand protection that feels right, even though it may do us more harm than good.

Now can you see why my conversation with my representative scared me WAY more than the risk I was calling about in the first place? We want our lawmakers to respect our values, but we also need them to be smart and careful, on our behalf. Lawmaking driven by the emotional nature of risk, and by political expedience – ignoring evidence of what will do us the most good – is a serious risk that should profoundly worry us all.