Why David Hockney Went Back to Nature

“If you want to replenish your visual thinking, you have to go back to nature,” David Hockney says in Bruno Wollheim’s film David Hockney: A Bigger Picture, “because there’s the infinite there, meaning you can’t think it up.” That film captures Hockney painting many of the amazing landscapes that appear in the exhibition David Hockney RA: A Bigger Picture, which appears at the Royal Academy in London through April 9, 2012. Striking a blow for painting in what he calls the “post-photographic age,” Hockney goes back to nature to revitalize his own art and, he hopes, save painting itself from Damien Hirst’s dots and other crimes against civilization.

By now everyone’s heard of Hockney’s proclamation for this exhibition that “[a]ll the works here were made by the artist himself, personally”—a clear shot across the bow of Hirst’s globe-spanning Gagosian dot painting shows, which feature works painted by Hirst’s assistants. The long decline of painting into decrepitude that began with Duchamp and continued with Pop Art may have finally hit rock bottom with the likes of Hirst and his self-professed boredom with painting his “own” paintings. Hockney emphasizes the creative act above all, going so far as to allow himself to be filmed by Wollheim painting in the Yorkshire countryside. When Wollheim filmed Hockney in 2003 for David Hockney: Double Portrait, the artist refused to be filmed painting his double portraits for fear of violating the connection between the subjects or the subjects and himself. Hockney exposes himself to Wollheim’s lens now because the relationship between him and nature is too powerful to be violated, and too powerful not to be shared.

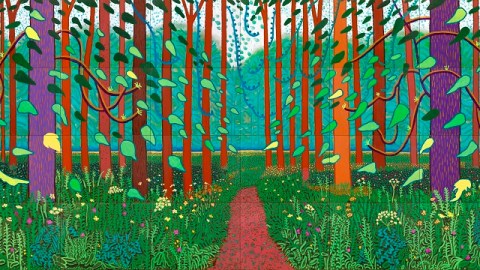

The show warms up with earlier landscapes from Hockney’s career ranging from the 1960s through the 1990s, just to prove that Hockney’s always been a landscapist at heart, whether he’s been in his native England or in his adopted home of California. All of that seems prologue to these works of the last 5 years, especially The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire in 2011 (twenty eleven) (detail shown above), a mammoth landscape (perhaps the largest ever painted out of doors) composed of 32 separate canvases joined together to grace the largest wall of the Royal Academy’s exhibition space. Hockney surrounds that tribute to nature’s largesse with more than 50 large-scale iPad drawings printed on paper that capture nature’s miniature glories.

Seeing these works by Hockney instantly made me think of the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s current exhibition Van Gogh: Up Close (which I reviewed here). The organizers of that show hoped to illustrate Vincent Van Gogh’s power to zoom in on the tiniest details of nature within larger landscapes. Powerfully rendered flowers and blades of grass, tops of trees cropped to focus on the texture of the trunks, high horizons drawing the eye down to earth—both Hockney and Van Gogh use these techniques to get back to nature. Van Gogh went back to nature for consolation and joy. Hockney finds those two benefits as well, plus the added benefit of resurrecting what he believes is the true path in painting. Whereas Van Gogh distrusted the still-young technology of photography as a rival to painting, Hockney believes that painting has left photography in its wake. In his “post-photographic age,” Hockney argues that the human mind and heart guide the artist’s hand to create images no camera can. Hockney embraces technologies such as the iPad because of the immediacy it offers. On a computer screen Hockney can paint fresh flowers each day and share them with friends with the push of a button. In one of the extras to Wollheim’s film David Hockney: A Bigger Picture, Hockney bemoans cyberspace’s “non-dimensional” character as no place for us “three-dimensional people.” Harnessing his own resources as one of the most influential painters of the last 50 years, the resources of today’s digital technology, and the resources of the Royal Academy’s generous galleries, Hockney restores painting to its three-dimensional roots as an extension of our natural environment and our own humanity.

David Hockney RA: A Bigger Picture embellishes the already well-established fact of David Hockney’s premier status in art starting back in the 1960s up to today. While other artists might rest on their laurels, Hockney pushes himself (and us, the viewers) to greater heights. These are landscapes for the 21st century painted by a 20th century artist with a faith in painting that reaches back to the Renaissance. Some artists think more than they feel; others feel more than think. Hockney remains that rare artist who both thinks and feels at the highest level—explaining in words why we need to see the world in a certain way and then allowing us to see and feel it through his eyes. David Hockney’s gone back to nature in a big way. The rest of us should (and need) to follow.

[Image:David Hockney. The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshirein 2011 (twenty eleven) (detail). Oil on 32 canvases (each 91.4 x 121.9 cm), 365.8 x 975.4 cm; one of a 52-part work. Courtesy of the artist. Copyright David Hockney. Photo credit: Jonathan Wilkinson.]

[Many thanks to the Royal Academy for the image above and other press materials for David Hockney RA: A Bigger Picture, which runs through April 9, 2012. Many thanks to Bruno Wollheim for providing review copies of his films David Hockney: Double Portrait and David Hockney: A Bigger Picture.]