Late Bloomer: “Late Renoir” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

“I think I’m beginning to know something about painting,” Pierre-Auguste Renoir said on the day he died as he turned away from a still life he’d been working on and handed his brushes to his assistant. Although wracked by the ravages of rheumatoid arthritis, Renoir painted prolifically to the end of his life in 1919. Late Renoir, an exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, examines the last three decades of Renoir’s oeuvre and demonstrates just how much the master had learned near life’s close. In those final years, surrounded by his growing family, Renoir bloomed into a deeper, more thoughtful, more joyous artist who reveled in the beauty of painting and escaped the pain of age into the joy of ageless art. “The pain subsides,” Renoir responded to questions concerning his painting with arthritis, “but the beauty remains.”

By 1890, Renoir had already become a famous artist. Unwilling to rest on those laurels, Renoir pushed his art to the boundaries of beauty. Part of that pushing forward consisted of a backwards glance towards art history. Renoir grew up in the shadow of the Louvre and haunted its halls throughout his life. In his catalogue essay, John House links Renoir’s late work to the art of Vermeer, Raphael, Veronese, Titian, Watteau, and Fragonard. All of these artists share a sense of classicism that appealed to Renoir as he looked to inject a timelessness into the abundant sense of beauty already overflowing in his art.

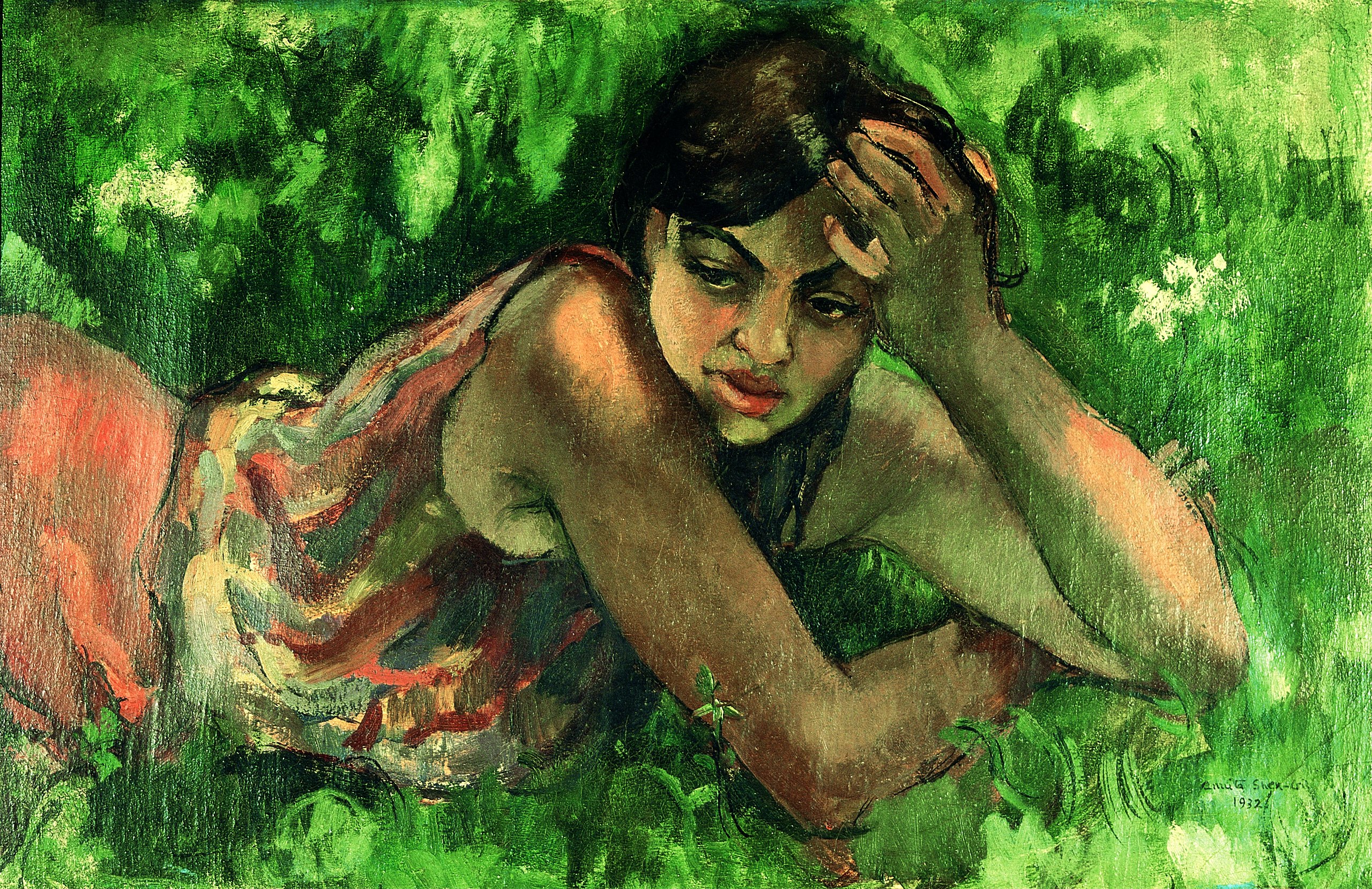

Renoir studied these artists and achieved effects of rendering human flesh that built upon their techniques but updated them as well. The luminosity of the skin of many of Renoir’s nudes in this exhibition stuns the senses. These women are literally glowing with life. Renoir loved to paint the women in his household, including those who cared for his young sons. The affection he felt for these young women lives on in the beauty of his painting.

Perhaps the greatest revelation of the exhibition is the focus on Renoir as sculptor. “Renoir the Sculptor?” Emmanuelle Heran titles her essay in the catalogue, echoing the question on most minds of how someone incapable of sculpting with his own hands could be a sculptor. Renoir “created” sculptures through the hands of a young sculptor named Richard Guino, who translated Renoir’s ideas into clay. These nude figures add a whole new dimension to Renoir’s lovely ladies of the late period. “For [Renoir],” Heran writes, “sculptural practice was the chance to conduct more in-depth studies of the monumental nude and its ongoing relationship to nature, and to resolve the tensions between line and contour, depth and volume, surface and light.” Renoir prioritized “the conquest of volume” in his final period, with sculpture serving as the battlefield of that conquest. This element of the exhibition elevates Renoir’s sculpture to the level of the sculpture of Degas, Picasso, and Matisse as the yin to the paintings’ yang.

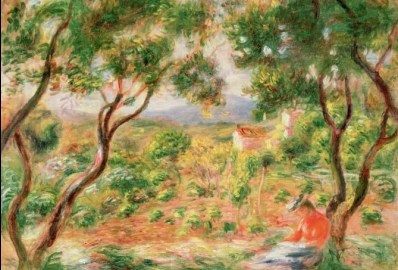

Just as the PMA presented last year Cezanne and Beyond as a way of connecting Cezanne to his descendents, Late Renoir connects Renoir to artists that followed, most importantly Picasso and Matisse, but also Malliol and Bonnard, among others. These connections remain a secondary focus of the exhibition, but they serve as reminders of just how influential Renoir was at the time painting in scenic Nice scenes such as 1908’s The Vineyards at Cagnes(pictured). Matisse made a pilgrimage to meet Renoir and fostered a friendship with the older artist. Picasso bought several works by Renoir and regretted never meeting the artist before it was too late. Jennifer Thompson, the show’s curator at PMA, wonderfully connects Renoir visually with the next generation in a way that bridges the Impressionists with all that followed.

It’s easy to imagine Renoir’s later years as a slow procession of pain. The beauty of the works belies that somewhat, but the real evidence came in the form of film footage of Renoir in his last years placed at the very end of the exhibition. Instead of a man crushed by infirmity, we see one, as curator Joseph Rishel puts it in the audio tour, “happy as a cricket” when placed before a canvas. Doctors gave Renoir the choice of walking or painting when the arthritis got worse, and you’ve never seen a happier wheelchair-bound person in your life. (Part of one of the videos is here.) The joy is simply infectious. It says much about the capacity of the human spirit to transcend the limitations of the flesh. Late Renoir teaches us that it’s never too late to learn even things that you felt you knew completely and that joy is an attitude more than anything else, and attainable against even the longest odds.

[Image:The Vineyards at Cagnes, 1908. Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French, 1841 – 1919). Oil on canvas, 18 1/4 x 21 3/4 inches. Framed: 27 3/8 x 31 1/4 x 4 1/4 inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Colonel and Mrs. E. W. Garbisch.]

[Many thanks to the Philadelphia Museum of Art for providing me with press materials and the catalogue for Late Renoir.]