How Howard Pyle Gave Our Heroes a Face

Peer into any young American boy’s imagination, and you’ll likely find knights, soldiers, and pirates roaming about. That fact is a true today as it was a century ago. One big reason for the enduring appeal of those figures is the art of Howard Pyle, the undisputed king of the Golden Age of American Illustration between the 1880s and the end of World War I. Marking the centennial of Pyle’s death, Howard Pyle: American Master Rediscovered at the Delaware Art Museum through March 4, 2012 will enlighten everyone who just asked “Howard who?” From American history books to Pirates of the Caribbean, the work of Howard Pyle continues to captivate us, despite his relatively forgotten place in American art history. Like pirates unearthing buried treasure, the organizers of Howard Pyle: American Master Rediscovered dig up the roots of American visual culture and recover Pyle’s power for a new generation.

“In almost any given month between 1877 and 1911, hundreds of thousands of Americans saw [Pyle’s] published pictures,” writes Delaware Art Museum curator Heather Campbell Coyle in the catalog. Yet, despite that widespread exposure, today only collectors, scholars, and working illustrators know Pyle, whose name rarely makes the pantheon of art survey classes—not for a lack of talent, but simply as part of the general critical disregard for illustration as one of the fine arts. With greater appreciation of the dynamics of visual culture—a mash-up of high, low, and middle brow—illustration is finally getting some respect as a vital source of public art literacy and appreciation.

Both a indefatigable illustrator and charismatic teacher, Pyle’s influence on American illustration was both broad and deep and even extended beyond his death in the work of his students. In an essay on “Pyle as a Picture Maker,” James Gurney explains how Pyle emphasized to his students the need to “live” in the picture. If you want to paint Washington’s troops shivering at Valley Forge, for example, Pyle believed that you need to know what it’s like to be that cold yourself. “Pyle liked to think of picture ideas in elemental terms,” Gurney contents. “It was vital that the picture express a single idea.” That single idea, soaring above technique, usually took the form of heroism.

In the wake of the 1876 Centennial, Americans hungered for a way to picture the days of the American Revolution. To accompany books and magazine articles about the Revolution, Pyle pictured battles and heroes, both famous and common. For every general on horseback, Pyle painted soldiers charging into the fray. As a nerdy nine-year-old growing up in Philadelphia, the epicenter of the Bicentennial, I hungrily consumed historical literature that still leaned heavily on Pyle’s work. Although I didn’t know Pyle’s name, his redcoats and patriots burned into my visual memory for good and became the definitive look of the time for me and many others. Pyle took pride in American history and saw his artistic career as a way of writing a new chapter of that history, specifically a form of American art free of European influence. For Pyle, only illustration could achieve that unique American-ness.

Despite that American dream for art, Pyle made use of European models when necessary, especially when it came to the world of knights and chivalry. Pyle’s own tetralogy of Arthurian works began with sources such as Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, but, as Alan and Barbara Lupack show in the catalog, Pyle “reinterpreted his sources and created ‘pictures,’ both visual and verbal, that were more than just ‘copies’… [to] create an entirely new version of the legends… clearly intended for young readers but one that never patronized them.” Part of that reinterpretation involved “Americanizing, or at least democratizing, the medieval legends,” according to the Lupacks. “Pyle suggests that by conducting themselves properly,” the Lupacks conclude, “his readers can achieve the moral equivalent of knighthood or kingship.” If punctuality is the courtesy of kings, then you, too, can be kingly by virtue of being on time.

Soldiers and knights acted as Pyle’s heroes, but it has been Pyle’s pirates—his antiheroes—that have stood the test of time the best. Anne M. Loechle analyzes Pyle’s pirates in all their paradoxical glory. For Loechle, Pyle’s audience could see pirates as a “fantasy of health” as agricultural America transitioned to office America, as a “fantasy of abundance” during an “era of extremes of poverty and wealth,” or as Robin Hoods taking from the rich (but giving only to themselves). In the end, however, Loechle sees Pyle using “pirate stories as a warning, an example of how the beginnings of moral breakdown can lead to total collapse.” Pirate power persists, however, because of the glamour of the evil—a glamour that translates wonderfully to film in everything from Douglas Fairbanks in The Black Pirate to Johnny Depp in Pirates of the Caribbean.

Walking through the exhibition and witnessing Pyle’s stylistic versatility, I found myself thinking of Mozart. In the 1780s, Mozart took his talents on the road, touring Europe and writing symphonies wherever he landed, often using local materials in his work. Similarly, Pyle borrowed freely when necessary, but always made it his own. The exhibition’s hanging emphasizes Pyle’s use of Albrecht Durer, Thomas Eakins, Ernest Meissonier, Jean-Leon Gerome, Winslow Homer, Aubrey Beardsley, the Pre-Raphaelites, and other artists well known by the public. “Emerging from a culture of transatlantic artistic exchange, Pyle’s success was abetted by his audience’s appreciation of his adaptation of American and European sources,” Margaretta Frederick explains in her catalog essay on Pyle’s place in his contemporary visual culture.

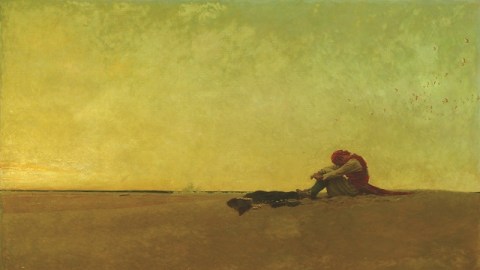

Just as local European audiences found an entryway into Mozart’s symphonies when a familiar tune resonated with them, visually literate audiences seeing Pyle’s The Retreat through the Jerseys would recognize and enjoy the same composition used by Meissonier for Campaign of France. But, where Meissonier shows Napoleon’s slumping troops trudging home dejectedly, Pyle depicts Washington’s battered but not beaten soldiers intently pressing forward. Pyle spoke body language fluently. You don’t need to know the story to know what’s happening in the character’s mind and soul. In Marooned (shown above), the solitary pirate with downcast head doesn’t need to tell you the name of the now tiny pirate ship sailing into the distance. You already know by the wide expanses of sand and sky that he is utterly alone. As David Lubin remarks in his catalog essay on Pyle’s pirates and their big screen afterlife, Pyle’s Marooned presages cinematic shorthand for human isolation such as Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’avventura, David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia, and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Yet, for all these echoes and continuing influences, Pyle remains marooned himself on the island of illustration. Howard Pyle: American Master Rediscoveredmasterfully rescues him from that fate. “Master rediscovered” is an overused term in museum exhibitions today, but this show and catalog live up to the name, just as Pyle’s sadly died over time. Pyle recognized the end of the Golden Age of Illustration coming and began the transition to mural painting. The ultimate American artist, Pyle died in 1911 in Florence (and is buried there) while studied the mural masters of the Italian tradition. What he would have done next is a great “What if?” Perhaps an even greater “What if?” lies in asking what American visual culture would have looked like without Howard Pyle. Howard Pyle: American Master Rediscovered raises such intriguing questions while laying out even more wonderful answers in Pyle’s pictures before you.

[Many thanks to the Delaware Art Museum for the image above and other press materials for Howard Pyle: American Master Rediscovered, which runs through March 4, 2012. Many thanks to the University of Pennsylvania Press for providing me with a review copy of the exhibition catalog. Special thanks to Margaretta S. Frederick, Chief Curator and Curator of the Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial Collection at the Delaware Art Museum, for showing me the exhibition and patiently answering my questions.]

[Image:Marooned, 1909. Howard Pyle (1853–1911). Oil on canvas, 40 x 60 inches. Delaware Art Museum, Museum Purchase, 1912.]