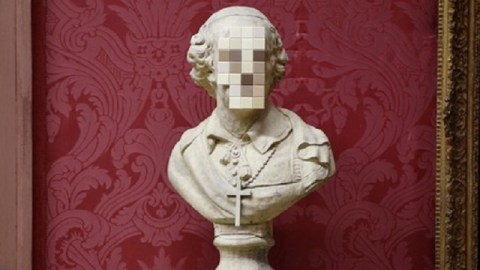

How Banksy Stole Christmas

With all apologies to the memory of Theodor Geisel, it’s not the Grinch stealing Christmas this year—it’s Banksy! In Cardinal Sin (above), Banksy takes a replica of an 18th century stone bust of a forgotten Catholic clergyman and defaces it by “de-facing” it and replacing the visage with a series of tiles. Timing the revelation for just before Christmas and choosing to “indefinitely” loan the piece to Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery, Banksy steals all the warm, fuzzy feelings of the holiday and forces us to face the chilling reality of the Catholic Church’s worldwide sex abuse scandal. Is this a valid religious-political statement or shameless self promotion—Banksy being Banksy even if it means ruining Christmas. You’re a mean one, Mr. B.

“The statue?” Banksy explained in a written statement. “I guess you could call it a Christmas present. At this time of the year, it’s easy to forget the true meaning of Christianity—the lies, the corruption, the abuse.” It’s hard to think of a darker view of Christianity and the Catholic Church than Banksy’s. But he’s not alone. As a Catholic who grew up in a Philadelphia parish mired in decades of sexual abuse of young boys by priests, I can see how such a negative opinion can become overwhelming. The Catholic Church has a long way to go to make things right. Cardinal Sin reminds us of how far they need to go. Banksy’s faux pixilation by bathroom tile mimics the video pixilation used to protect identities, but in this case creates a faceless, damning everyman (everypriest?). The generalization’s unfair, of course, but understandable because of the nature and magnitude of the crimes and the cover-up.

Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery is an apt home for Cardinal Sin for two reasons. Firstly, Liverpool and Ireland still suffer greatly from their local sexual abuse scandals and the mishandling by the Church. Secondly, the gallery owns a beautiful collection of Christian art from the glory days of the Catholic Church. Cardinal Sin sits just a turn of the head away from Rubens‘ The Virgin and Child with St Elizabeth and the Child Baptist is the most well-known piece in the gallery. Banksy leaves the dangling cross and lavish drapery of the defaced bust intact as damning signs of the past power of the Catholic Church steeped in greed and corruption. Banksy asks us to draw parallels from the present to this romanticized past and to question the basics of the faith, including Christmas, even in the commercialized form we know it as today.

Enter The Guardian’s Johnathan Jones. In a recent post, Jones decried Cardinal Sin as “mak[ing] such an obvious point that it does not reach the depths that real art does. It does not touch the viscera, the soul, or the remoter parts of the brain.” Jones credits Banksy for respecting the Old Masters and bringing attention to the Walker’s collection, but, in the end, still finds the new piece more boring than controversial. I’m not sure that Jones reads Banksy correctly. I think Banksy’s affection for Rubens and friends lies more in how he can use (or abuse) them than in aesthetic pleasure. I also think that Jones is unfairly reading Banksy’s statement piece. If obviousness is an art crime, then David’s neo-classical love letters to the French Revolution fail, too. How subtle are the screaming faces of Picasso’s Guernica? I’m not suggesting that Cardinal Sin will find a similar place in the canon as David and Picasso’s political art, but I do believe that it shouldn’t be disqualified for being as clear as those artists were.

Before we begin praying for Banksy’s heart to grow three sizes larger so he’ll take Cardinal Sin back and save Christmas, let’s take a moment and give him the benefit of a doubt. Forget for a moment Banksy the brand and imagine Banksy the social commentator. The Catholic Church and Christianity are not the sex abuse scandal and those who facilitated it and continue to deny it. Cardinal Sin, by making people think of worldly power versus sacred truths, might actually save Christmas—the celebration of life in the form of a tiny child of hope—in the end. Like the Whos in Whoville, we may gather around Cardinal Sin and sing, “Welcome, Christmas, while we stand/ Heart to heart,… and hand in hand.”