The science behind why our brains make us cooperate (or disagree)

- Neuroscientists identify the parts of the brain that affect our social decision-making.

- Guilt has a large affect on social interactions, find the researchers.

- To find ways to cooperate, people need to let go of fear and anxiety, suggest studies

Why do we decide to work on a project or pursue a goal with someone? Or why do we treat some people like there’s no way we can find any common language? Neuroscience says that the human brain contains underlying causes to all human cooperation and social decision-making.

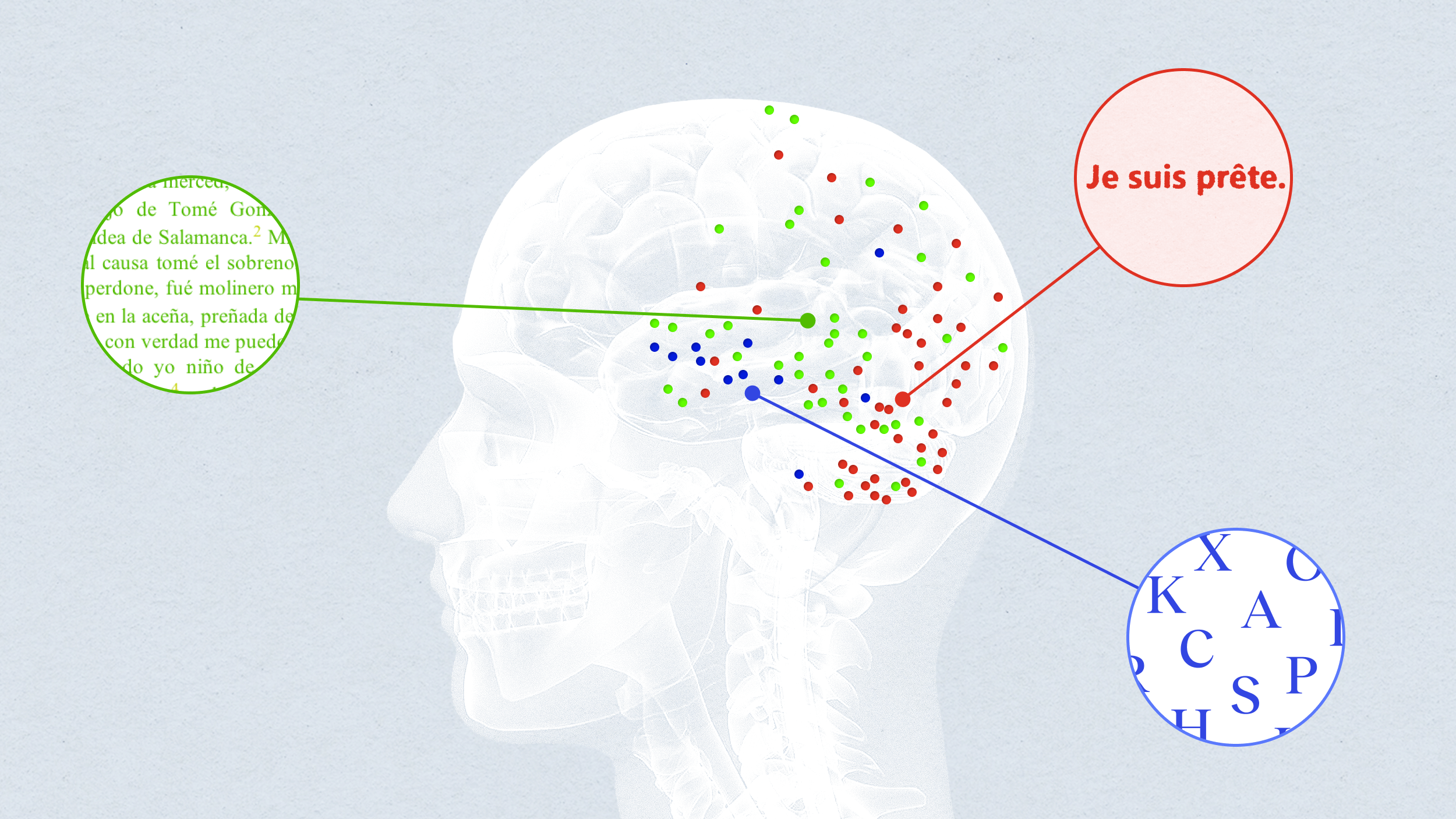

One difficulty in studying human behavior is that it’s hard to record brain activity while the behavior is happening. You don’t see many people outfitted with MRIs as they confront each other in the ebb and flow of daily life. But a new slate of advanced devices allowed neuroscientists a greater peek behind the mind’s curtain. Studies presented at the 2017 annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience offered a variety of explanations for our behavior with respect to others.

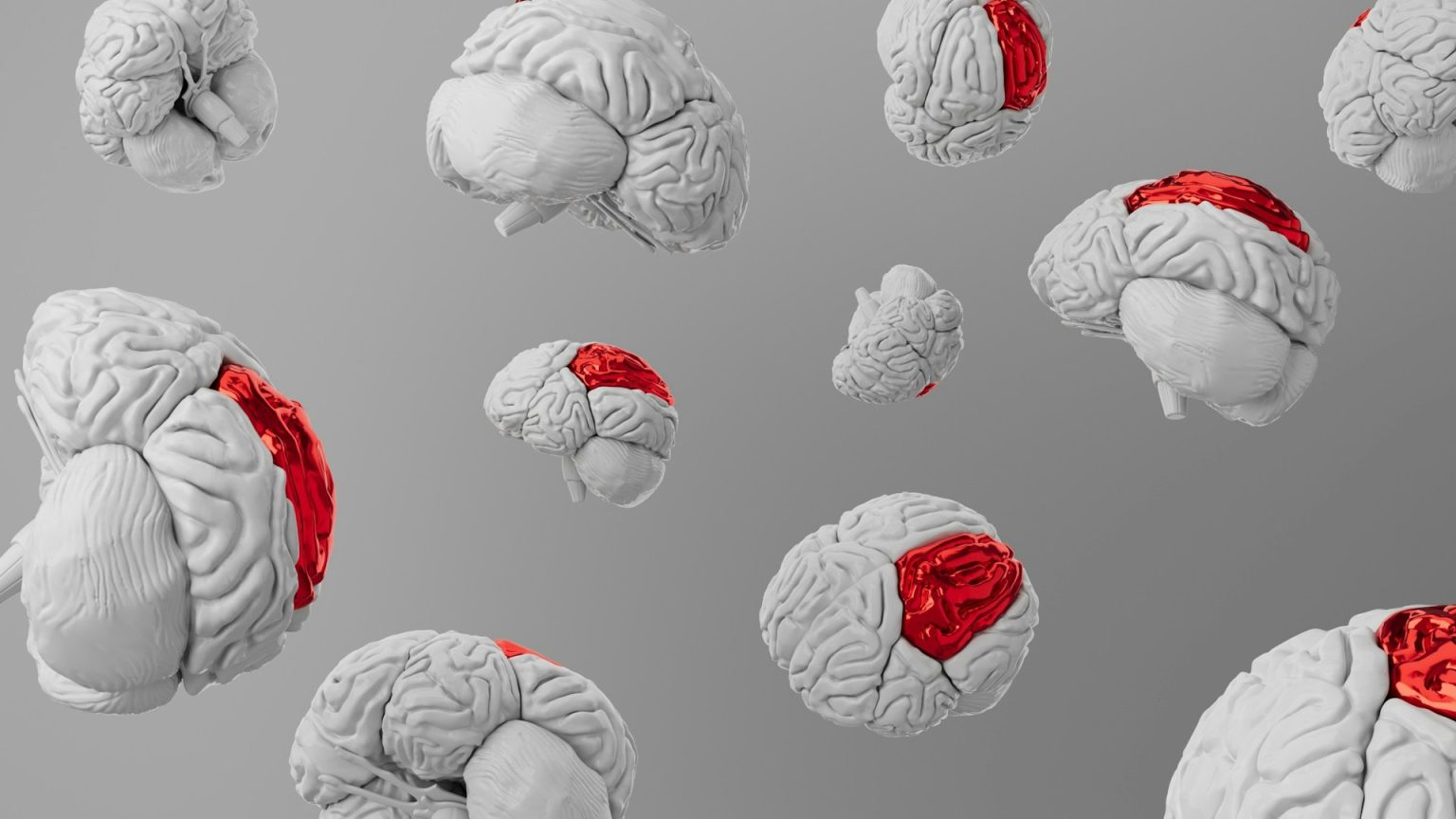

What the scientists found is that a wide array of neural circuits are engaged when we interact with others socially. Research on mice showed that when an area of the hippocampus, which is responsible for our memories, is stimulated, aggression increases. This suggests that memories can impact social aggression.

Such a conclusion gels with our experience. Memories of a past wrong often inform our actions. It follows also that for aggression to be minimized, memories should not play such a strong role in how we make decisions. In reality, of course, that is a hard goal to achieve for some.

Another area of the brain that affects our social life is the amygdala, the gray matter present in each cerebral hemisphere that impacts our emotions, especially fear. Researchers found that neuronal activity in the amygdala of primates is involved in predicting choices made by a partner. That suggests how this part of the brain has an impact on our observational learning and decision-making in social situations.

Lest you think humans are driven by altruistic motives during games, neuroscientists also learned that strategic thinking rather than empathy is an important piece of the puzzle that’s responsible for how we make decisions with respect to others.

Once we are already working with a person, research has shown that the neural activity in the primary motor cortices of monkeys performing a social task can become highly synchronized. This area of the brain relates information about the task but also makes note of how close the two primates are to each other.

Psychiatry and neuroscience Professor Robert Greene from the University of Texas, confirmed that “we now see evidence of shared and interactive neuronal activity between social partners that extends to such things as cooperative behavior and learning and decision-making.”

Notably, a study from 2011 by a team of University of Arizona researchers, found another key aspect that drives human cooperation (or lack thereof) – guilt. By using fMRI imaging on participants playing economic games, the scientists discovered much activity in areas of the brain involved in guilt-related behaviors. This was particularly so when the subjects decided to return money expected by hypothetical investors. When the participants decided not to return the money, the reward center of the brain lit up.

This means that two different neural structures are involved when we ponder whether to meet someone’s expectations. Guilt has significant influence on the decision to cooperate with someone. Of course, as the researchers also showed, some people are more affected by feelings of guilt than others.

Guilt can also drive our feelings of moral outrage, in a fact that explains why much of our interaction on social media often devolves into anger rather than a desire to collaborate. A 2017 study from psychology professors Dr. Zachary Rothschild from Bowdoin College and Dr. Lucas Keefer from the University of Southern Mississippi linked feelings of guilt to making people angrier, causing a desire to punish third parties. In particular, American subjects of the study who read that Americans were responsible for driving climate change (rather than, for example, the Chinese) were more likely to get outraged with “multinational oil corporations”. Another reason for that, as the researched uncovered, moral outrage makes you feel less guilty and more moral.

How do we get beyond some of the instinctual responses of our brain that may prevent us from cooperating with others? In a video for Big Think, Sarah Ruger, the director of Free Expression, at the Charles Koch Institute, highlights the work of neuroscientist Dr. Beau Lotto, who suggests that awe and play “can cause people to let go of their fear, let go of their anxiety so that they enter a mental state where they’re capable of being curious and entertaining a new experience.” Check out her video here:

When we encounter disagreeable ideas and situations where we just don’t agree with someone, we don’t often think about our brain’s role in our ultimate reaction to the situation. But if we are mindful of the processes that take place, we should be able to take a larger view and find the courage to get past the sticking points, moving towards cooperation.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this video do not necessarily reflect the views of the Charles Koch Foundation, which encourages the expression of diverse viewpoints within a culture of civil discourse and mutual respect.