Does Islam Really Subjugate Women?

There is popular narrative in the West that Islam is sexist. Brutal accounts of honor killings and public stonings of women accused of adultery have permeated the Western media. But these heinous acts affect a small minority of the world’s 1.5 billion Muslims, particularly those in fundamentalist countries like Iran and Somalia. What of the hundreds of millions of other female Muslims around the globe, from Indonesia to Egypt, from China to Germany? Does moderate Islam deny them freedoms in their daily lives, or is this a convenient narrative to justify anti-Islamic sentiment?

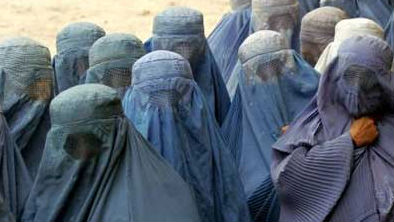

The Koran cautions women “to draw their outergarments close around themselves” so that they will not inspire sexual desire in men other than their husbands. Many in the West decry the various headcoverings as sexist, but their implementation differs widely in the Muslim world. In Saudi Arabia women typically wear a niqab, a full-body garment with a veil that obscures the face. While in Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim country, headcoverings are completely optional and actually used often as a fashion statement. In Turkey and France, burqas, full-body garments with or without a veil, are banned in public. French President Nicholas Sarkozy has called the burqa “not a sign of religion [but] a sign of subservience.”

Afghan filmmaker Sonia Nassery Cole doesn’t wear a headscarf herself, but she believes that women should be able to wear whatever makes them feel safe and beautiful. If that happens to be a burqa, France has “no right” to ban it, she says. Cole grew up Muslim in Afghanistan but fled to the United States shortly after the Soviet invasion in 1979. Ever since she has campaigned for women’s and children’s rights from abroad, serving on the board of the Afghanistan Relief Committee and establishing the Afghanistan World Foundation.

But when she returned to Afghanistan in 2009 to spearhead aid efforts and to make her first feature film “The Black Tulip,” what she found was nothing like the Afghanistan of her childhood. Under the Taliban, “the country went like 500 years backward,” she tells Big Think. “There are pictures I have seen of my mom and her friends wearing high boots, miniskirts, dancing, going to work with beautiful suits, above the knee skirts, high heels,” she recalls.

As Nassery Cole paints it, Afghanistan used to be a bastion of equality for women. “Afghan women had their rights before European and American women even knew what rights were,” she says. “My mother was a very powerful woman and she [stood] shoulder to shoulder with my father; she worked with him all the time, even when he was a diplomat.” She says her grandmother was indisputably the boss of the house. Cole admits that the Koran can be interpreted to promote misogyny, as it is by the Taliban, “but the essence of Islam is the highest respect for women,” she says. Fundamentalist interpretations of the Koran are the enemy, not the Koran itself.

But author and activist Ayaan Hirsi Ali sees Islam as antithetical to liberalism and women’s rights. A former Muslim herself, she has been one of Islam’s most vocal critics. As she discusses in her Big Think interview, her Islamic upbringing was nothing like Cole’s: “When I was a Muslim woman, we were brought up to believe in our own submission—submission to the will of God, submission to the will of your parents, submission to the will of your husband. And submission to the will of the husband is absolute except when he asks you to forsake Allah.”

Naturally there will be fundamentalists in any religion, who insist on literal interpretations of outdated dogma. But the problem is not just with fundamentalism, but with Islam itself, says Hirsi Ali. In her book “The Caged Virgin: An Emancipation for Women and Islam,” she pinpoints three reasons why the Muslim world lags behind the West and, increasingly, Asia. First, “Islam is strongly dominated by a sexual morality derived from tribal Arab values dating from the time the Prophet received his instructions from Allah, a culture in which women were the property of their fathers, brothers, uncles, grandfathers, or guardians,” she says. “The essence of a woman is reduced to her hymen. Her veil functions as a constant reminder to the outside world of this stifling morality that makes Muslim men the owners of women and obliges them to prevent their mothers, sisters, aunts, sisters-in-law, cousins, nieces, and wives from having sexual contact.”

But the holy books of Christianity and Judaism were written hundreds of years before the Koran, in even less enlightened times. In the Ten Commandments, for instance, women are clearly viewed as property: “Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s house, thou shalt not covet thy neighbor’s wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor any thing that is thy neighbor’s.” In this litany, women are listed alongside slaves (manservants and maidservants) and animals, suggesting a similar status. These books do not jibe with our modern interpretations of women, yet mainstream Christianity and Judaism have evolved over the years.

Secondly, a Muslim’s relationship with God is ontologically different than a Christian’s, says Hirsi Ali. “A Muslim’s relationship with his God is one of fear,” she says. “He punishes you cruelly if you break His rules, both on earth, with illness and natural disasters, and in the hereafter, with hellfire.” When she emigrated to the West at age 22, Hirsi Ali realized that “God and His truth had been humanized here.” Instead of focusing on Hell and punishment, Christianity focuses on salvation. For Christians, “God is a god of love rather than a cruel ruler who metes out punishments.”

But perhaps the main difference is that Islam has one moral source, the Prophet Muhammad, who was himself a human. “Muhammad is infallible,” says Ali. “You would almost believe he is himself a god, but the Koran says explicitly that Muhammad is a human being; he is a supreme human being, though, the most perfect human being.” And Muhammad, a seventh century man, has become an example for all Muslim men, she told the Dutch publication Trouw. There are thousands of hadith, accounts of Muhammad’s words and actions, which explain how a seventh century Muslim was supposed to live. Yet devout twenty-first century Muslims also consult these writings for daily guidance. Things that were acceptable then, like marrying a 6-year-old girl, are clearly not acceptable in 2010. By Western standards the Prophet would now be considered a pervert, Hirsi Ali has said.

More Resources

Faisal al Yafai, “Translating feminism into Islam“

Lily Zakiyah Munir, “The Koran’s Spirit of Gender Equality”

An earlier version of this article described imprecisely how the Prophet Muhammad communicated with Allah to inspire the Koran. Muhammad did not “write” the Koran, but was instead its “moral source.” The article has been amended to reflect that.