Graphic Content: Graphic Art of German Expressionism at the MoMA

“Like everything genuine, its inner life guarantees its truth,” German artist Franz Marc once wrote. “All works of art created by truthful minds without regard for the work’s conventional exterior remain genuine for all times.” When the German Expressionists searched for a way to get back to basics and recover for the present what they saw as the lost primitive passions of the past, they turned to printmaking and the graphic arts as the ideal medium. In German Expressionism: The Graphic Impulse, which runs at the Museum of Modern Art throughJuly 11, 2011, the glory days of German Expressionism, both before and after World War I, live again. The content of these graphic works—life, love, war, peace—inspires, informs, and even offends, but never fails to touch something inside you with the “genuine” force Marc wrote about that “guarantees its truth.”

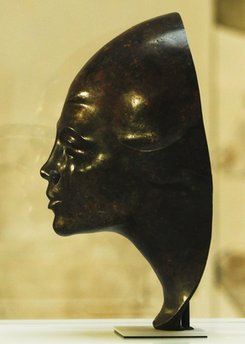

“The Expressionists believed that the arts could play a central role in aesthetic and social renewal,” one wall text of the exhibition explains. “In their efforts to tap into ‘vital forces’ or ‘inner feelings,’ many were influenced by the art of ‘primitive’ and non-European cultures, which offered, it was felt, an emotionally immediate and authentic mode of expression in contrast to the academic refinement and bourgeois placidity that characterized the art and culture of Europe.” Although the German Expressionists looked outside their culture for source material or at least primitive “vital forces” that culture had swept away, they also looked to Albrecht Durer as an exemplary figure in their own Germanic tradition. Durer’s iconic woodcuts and graphic work inspired figures from the Brücke (especially Ernst Ludwig Kirchner) and Der Blaue Reiter (led by Marc and Vasily Kandinsky) to make printmaking integral to their artmaking, which was to be an art for the masses rather than the elite.

It’s this fascinating stew of influences and aims that makes The Graphic Impulse so fascinating. Anyone who has paid attention to the Neue Galerie’s exhibitions for the past few years knows well the influence of Van Gogh on the Expressionists. The German Expressionists were the first to recognize the power both of Van Gogh’s art and his life. They hungrily devoured Van Gogh’s letters and adopted his almost evangelical approach to art immediately. If Van Gogh can be said to have had disciples, they would most certainly be these German artists. How to help humanity through graphic art, however, is where the roads these artists took diverge.

Kirchner and his fellow Brücke artists Erich Heckel, Max Pechstein, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff depicted the everyday life of pre-World War I Germany, which they saw through their bohemian eyes as hypocritical and repressed. By holding up a mirror to society, Brücke hoped to awaken the masses from their somnambulism. Unfortunately, part of that rude awakening took the form of the Great War itself. Similarly, Kandinsky and Marc of Der Blaue Reiter longed for a rebirth of German society, but in a more abstract way. Marc found his vital force to be emulated in animals. His Riding School After Ridinger (Reitschule nach Ridinger) (shown above) masterfully captures the raw animal energy of horse riding—a symbol for the energy Marc wanted to infuse into the lifeless modern world. Unfortunately, their generation rode that energy straight into the heartless maw of modern warfare. Marc and August Macke, another artist of Der Blaue Reiter, died in action. Both Der Blaue Reiter and Brücke failed to survive the war as artistic movements.

After the groundwork laid and sacrifices of those two movements, the show becomes a greatest hits parade of German and Austrian Expressionism from during the war and immediately after, during the decadent days of Weimar. Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele’s drawings and watercolors tap into the repressed sexuality that ideas of their fellow Austrian, Sigmund Freud, were just beginning to bring to light. Otto Dix and George Grosz took their war experiences and cast a caustic eye on both war and the hopeless peace burdening the German people in the aftermath of Versailles. Dix’s 1924 collection titled The War shows shock troupes advancing through gas warfare, trenches disintegrating and burying their occupants alive, landscapes blighted by bombing, and other sights that the public preferred to forget in the 1920s, but Dix and others continued to force upon their consciousness. Looking at Dix’s work today in the midst of the endless War on Terror reminds us of the cost of war in our own times.

It’s that timelessness of these messages—the “impulse” behind German Expressionism: The Graphic Impulse—that makes these works so stirring and unforgettable. Another early honorary German Expressionist adopted before the world discovered him was Edvard Munch, whose The Scream ranks among the most unforgettable single images of modern art. The Graphic Impulse comprises one giant “scream” of joy, love, anger, and terror simultaneously. We often avert our eyes from the graphic content of violence and sexuality. Through graphic works on paper—the simplest and most easily distributed medium—these artists made it impossible for us to avert our eyes any longer.

[Image:Franz Marc. Riding School After Ridinger (Reitschule nach Ridinger). 1913. Woodcut. Composition: 10 9/16 x 11 3/4″ (26.9 x 29.8 cm); sheet: 12 13/16 x 14 3/4″ (32.5 x 37.5 cm). Publisher: unpublished. Printer: Maria Marc. Edition: One of an unknown number of posthumous impressions. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, 1940.]

[Many thanks to the Museum of Modern Art for providing me with the image above and other press materials for German Expressionism: The Graphic Impulse, which runs throughJuly 11, 2011.]