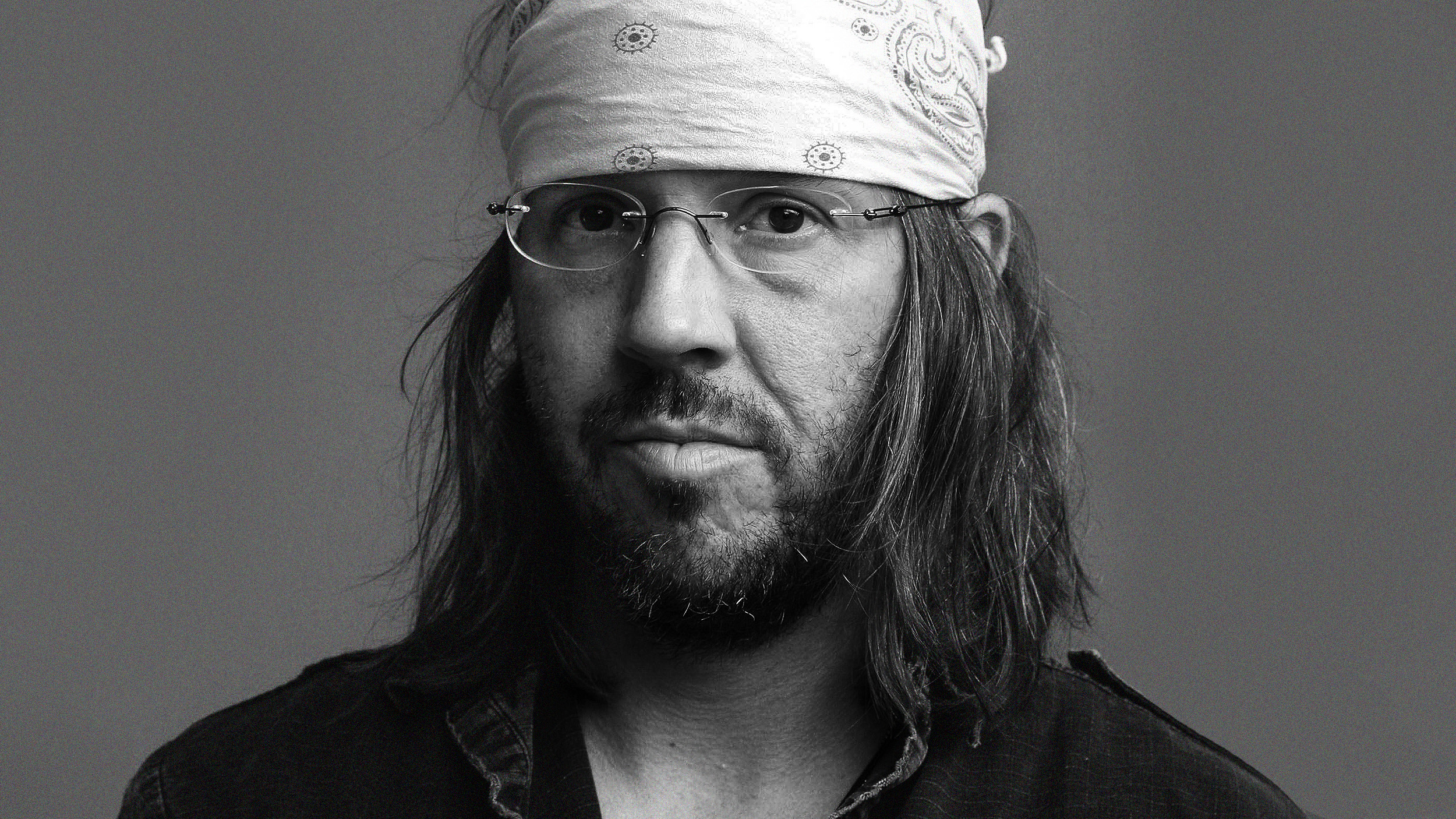

Shakespeare and David Foster Wallace: The Pale King and Hamlet

Looking at the language of critical response to the novel, there are parallels. This is not to say that David Foster Wallace cared for Hamlet. But he seemed to care for ontology. The question of what life means and how to bear it in a castle among kings and queens (even murderers) is one thing, but how to bear it in The Pale King, in an office, is another. Art applied to the big questions illuminates and mocks the prospects for answers, but as we will never stop asking, we will always need writers we love to re-frame it for us.

The Question is, To Be Or Not To Be?

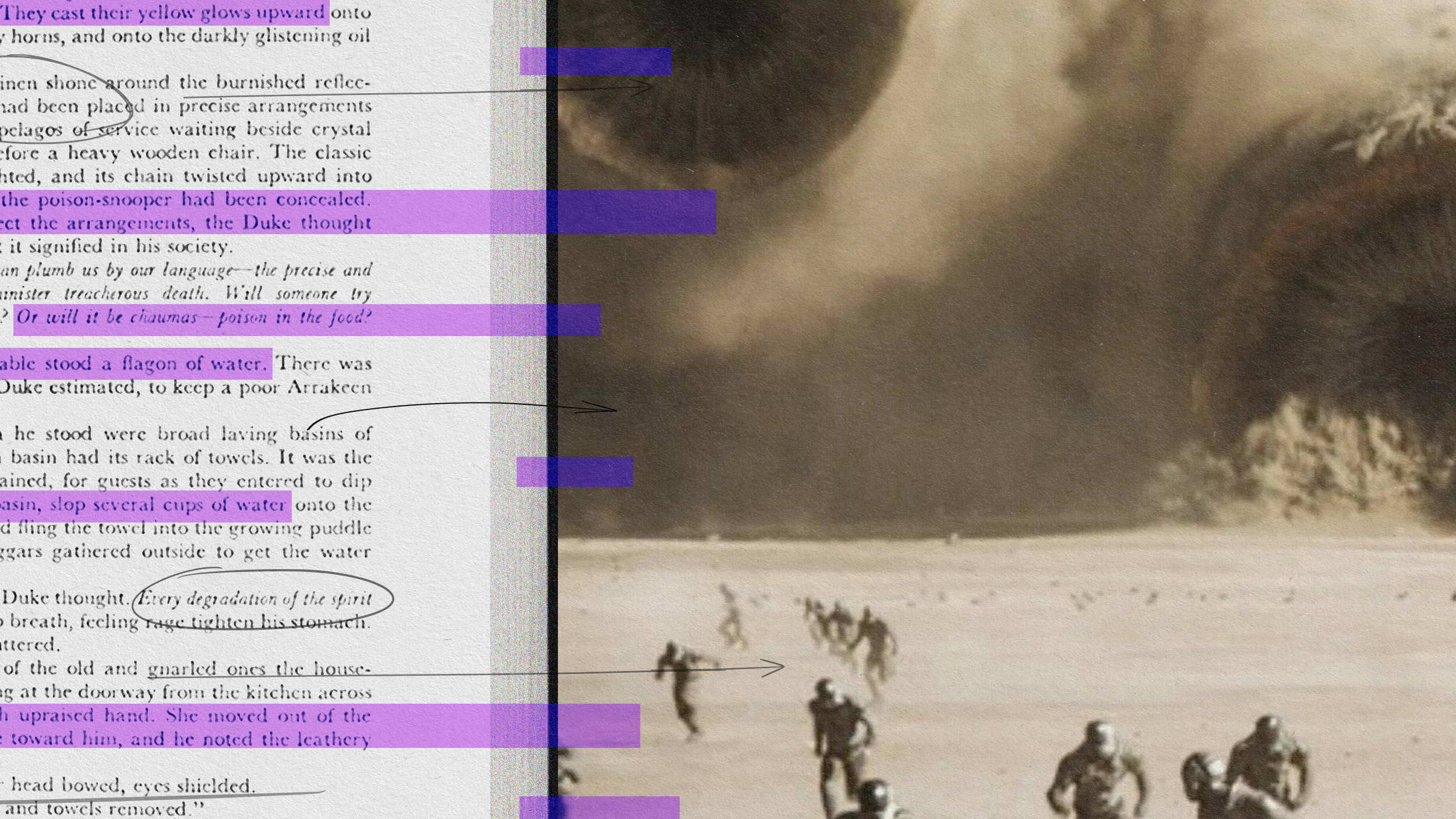

Tom McCarthy, in today’s New York Times, considers whether The Pace King is, at least in part, a consideration of the problems of writing a novel. He writes that:

“Lost childhood pools, by this reading, would constitute a kind of pastoral mode cached (or trashed) within the postmodern ‘systems’ novel—which, in turn, is what the systems-within-systems I.R.S. really stands for. The issues of emotion and agency remain central, but are incorporated into a larger argument about the possibility or otherwise of these things within contemporary fiction. The data-psychic character Sylvanshine can glean trivia about anyone simply by looking at him, but is “weak or defective in the area of will.” Nor, due to endless digressions, can he complete anything. No one can; in The Pale King, nothing ever fully happens.”

Weak or defective in the area of will. Endless digressions. Nothing ever fully happens. This sounds like Hamlet (the prince, not the play). That was his issue: how to go on? Maybe Wallace sought a solution somewhere between murder and apathy, between Elizabethan splendor and a mound of sand.

The Insolence of Office

Consider this:

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause: there’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life;

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

The oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office and the spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscover’d country from whose bourn

No traveler returns, puzzles the will

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all —–

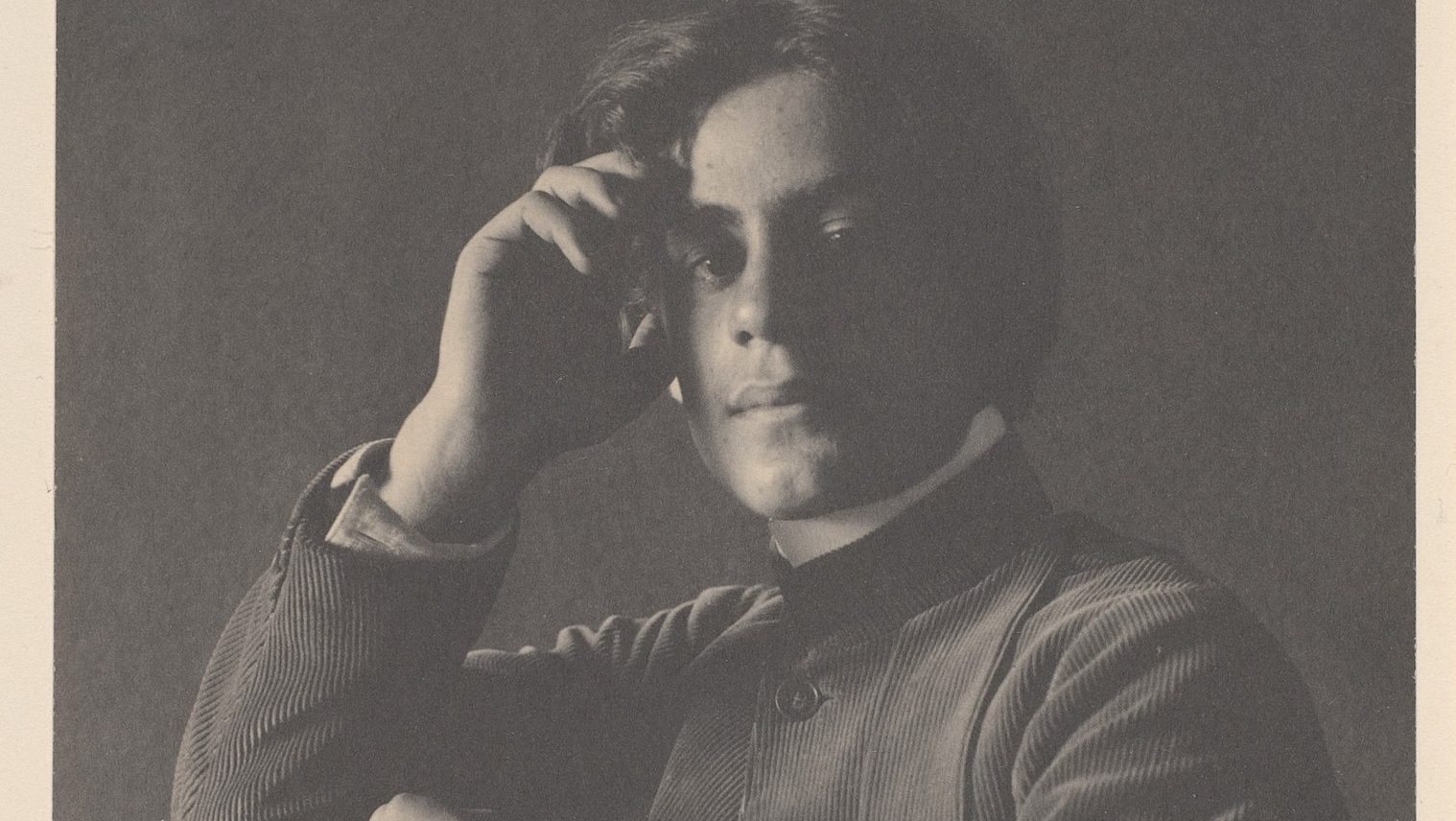

Hamlet is also a play about mourning. A prince has lost his father. And when we lose a writer, we lose the one critic who could have told us what he meant. “[Wallace] loved writing fiction,” Jonathan Franzen writes in The New Yorker. “He’d loved writing Infinite Jest in particular, and he’d been very explicit, in our many discussions of the purpose of novels, about his belief that fiction is a solution, the best solution, to the problem of existential solitude.” Like the meaning of Hamlet, the intentions of novels that outlive their authors will be debated. Theorists might advise readers to focus on the text and forget the rest. The words are the writer, they might say. The rest is silence.