Is Cyberwarfare the Nuclear Warfare of Our Generation?

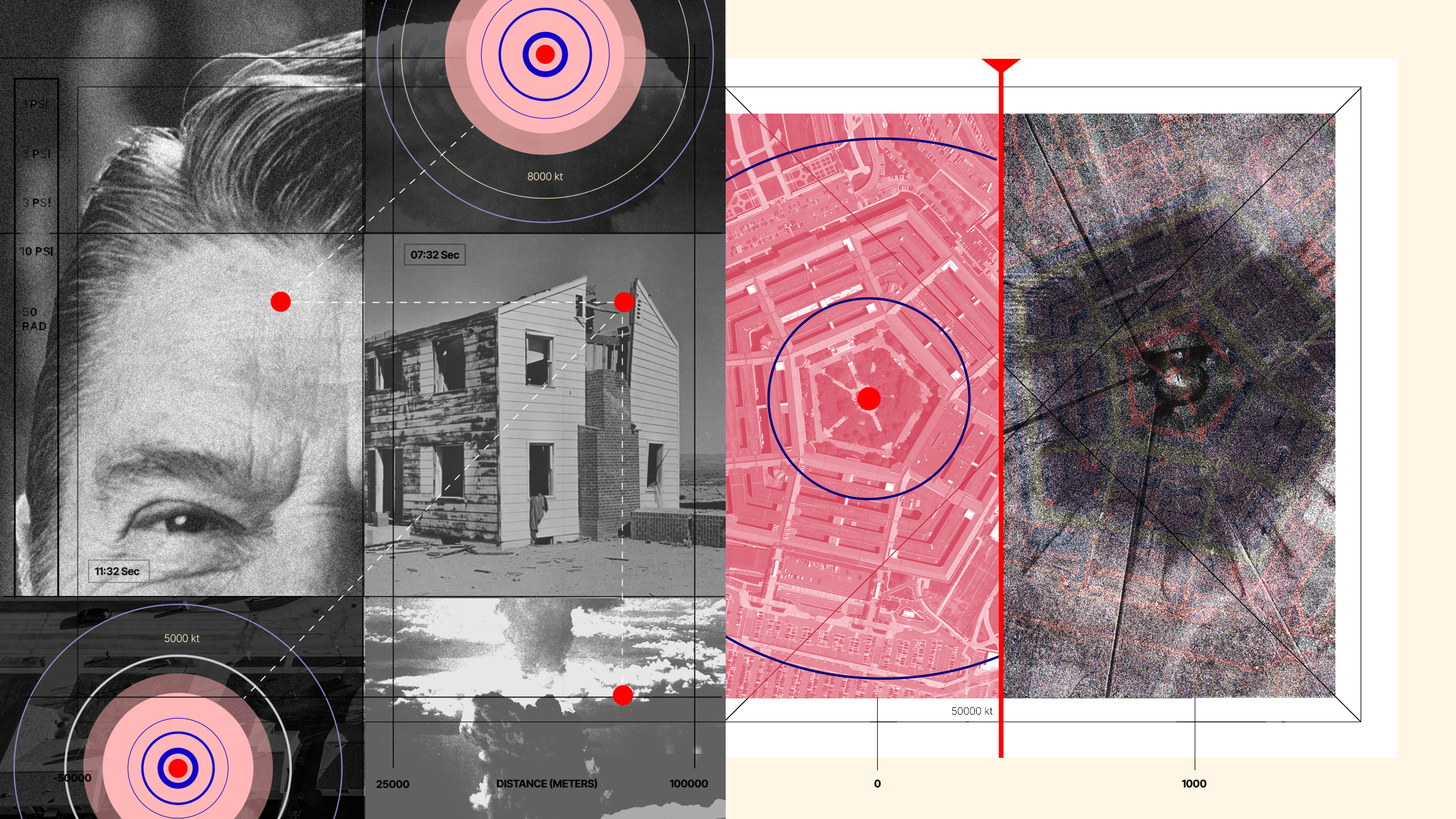

The U.S. has gone to war over the surprise attack of its naval fleet in Pearl Harbor, the torpedo attack on warships in the Gulf of Tonkin, and indiscriminate attacks on ships in the North Atlantic. But is the U.S. prepared to go to war over an attempt to shut down its electrical grid or malicious attempts to hack into classified accounts on the Internet? One thing is certain: cyberattacks on U.S. private computer networks have been escalating over the past year, and in response, the Pentagon has begun to outline the rules of engagement for cyberwarfare. As one military official bluntly put it, “If you shut down our power grid, maybe we will put a missile down one of your smokestacks.”

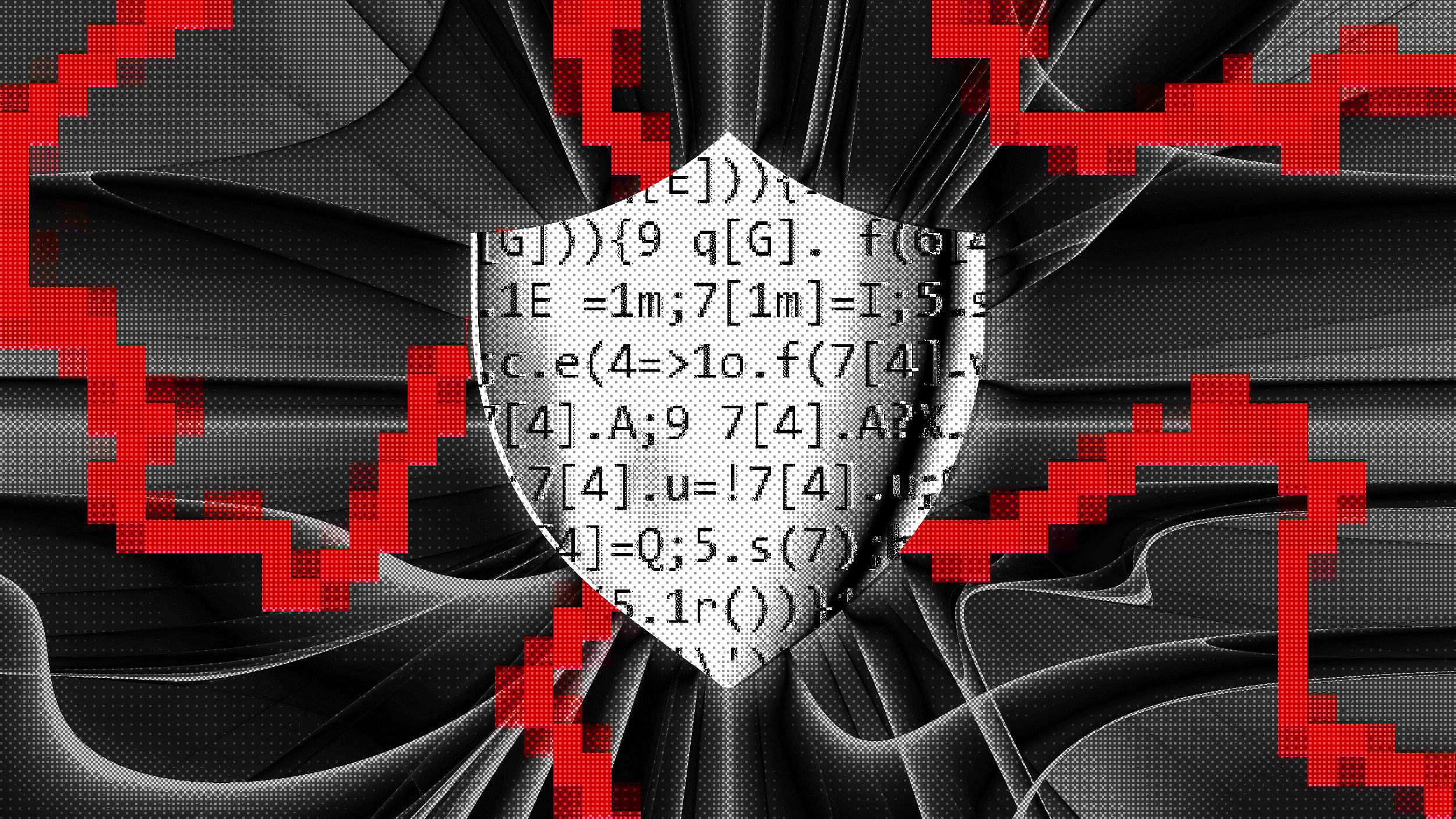

Cyberwarfare may sound like something out of a Philip K. Dick novel (and, in fact, the term “cyber” dates way back to Norbert Wiener and the Cold War era), but it has become a reality for U.S. corporations as well as the U.S. government. Nobody, it seems, is safe. Just this week, U.S. government officials admitted that persistent cyber-warriors had attempted to hack into non-secure Google Gmail accounts as a back door into classified security secrets. Weeks earlier, huge defense contractor Lockheed-Martin found itself the subject of sustained, ongoing attacks from hackers in China. All told, more than 100 foreign intelligence organizations have attempted to break in to the U.S. government’s secure compuetr systems – and that’s just what we know about.

The growth of cyberwarfare reflects the continued evolution in the nature of asymmetric warfare. You thought it was hard doing battle with the mujahadeen in the mountains and caves of Afghanistan? How about doing battle with the new generation of global cyber-warrior, who can disguise his or her identity and use nearly any computer or mobile device in the world to carry out an attack? It may be possible to retaliate against nation-states, but how do you carry out an attack against a nameless, faceless entity who may or may not be acting according to national security plans? How do you respond to a couple of guys with a laptop who take down the Internet in New York or Chicago or L.A.?

The 800-pound gorilla in the room, of course, is China. Even when policymakers talk about defending themselves from cyberwarfare threats, they are really talking about defending themselves against China. And, make no mistake about it — there are already influential elements within China that equate cyberwarfare as the strategic war of the information era, just as nuclear war was the strategic war of the industrial era. (And let’s not be naïve, the U.S. has been playing around with cyberwarfare of its own, including rumors that it was behind the famous Stuxnet worm in Iran’s nuclear reactors.)

What does that mean for the future of the U.S. government’s cyberwarfare policy? Certainly, it’s a good sign that the White House has started to lay out its strategy for cyberspace and has started to accelerate federal hiring efforts on cyber-security experts. More needs to be done – and quickly – to ensure that the nation’s mission-critical systems are safe from cyberattack. Defense is the best offense. Truth be told, though, it’s all a bit reminiscent of the Cold War era, when we lived under constant threat of nuclear attacks from enemies on the other side of the Iron Curtain.

We also need to decide when a cyber-attack justifies a military response, and how vigorously we should respond. Just as we did with nukes, the U.S. Pentagon is already establishing the rules of engagement so that every alleged cyberattack does not result in a military strike. The Pentagon’s currently policy is that it will only hit back with a military strike if a cyberattack causes the type of damage and mayhem associated with a traditional military attack. Before carrying out an attack – of any kind – we need to be able to identify our attackers with 99% certitude, and that’s where things get dicey. After all, the worst thing in the world would be The Elderly Woman in Tblisi situation, where the Internet gets shut down due to a completely random mishap, and we start launching missiles at China in retaliatory response.

[image via Wikimedia Commons]