Life Redefined: “The Devil’s Dictionary” Turns 100

A century after its publication as The Devil’s Dictionary, Ambrose Bierce’s comic lexicon remains a beautifully nasty piece of work. Though it’s a work of satire first and foremost, its mock definitions incorporate whimsy, existential pessimism, cheap puns, sex jokes, and just about every other trick in the comedian’s book. Here’s a quick sampling of my favorite entries:

SELF-ESTEEM, n. An erroneous appraisement.

SELFISH, adj. Devoid of consideration for the selfishness of others.

OBSOLETE, adj. No longer used by the timid. Said chiefly of words.

LIFE, n. A spiritual pickle preserving the body from decay. We live in daily apprehension of its loss; yet when lost it is not missed. The question, “Is life worth living?” has been much discussed; particularly by those who think it is not, many of whom have written at great length in support of their view, and by careful observance of the laws of health enjoyed for long terms of years the honors of successful controversy.

HASH, x. There is no definition for this word—nobody knows what hash is.

Like hash, Bierce himself was defiantly uncategorizable. His career is one of the oddities of American literature; after the Dictionary, his second best-known work is the eerie short story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” which has inspired multiple film and TV adaptations. (Probably the most famous of these aired in the ’60s as an episode of The Twilight Zone.) Along with his sister in cynicism, Dorothy Parker, he is quoted constantly, but few writers claim him as an influence. Exceptions include Kurt Vonnegut, who greatly admired “Owl Creek”—“I consider anyone a Twerp who hasn’t read [it]”—and the Australian writer Peter Bowler, whose Superior Person’s Book of Words series I’ve loved since childhood.

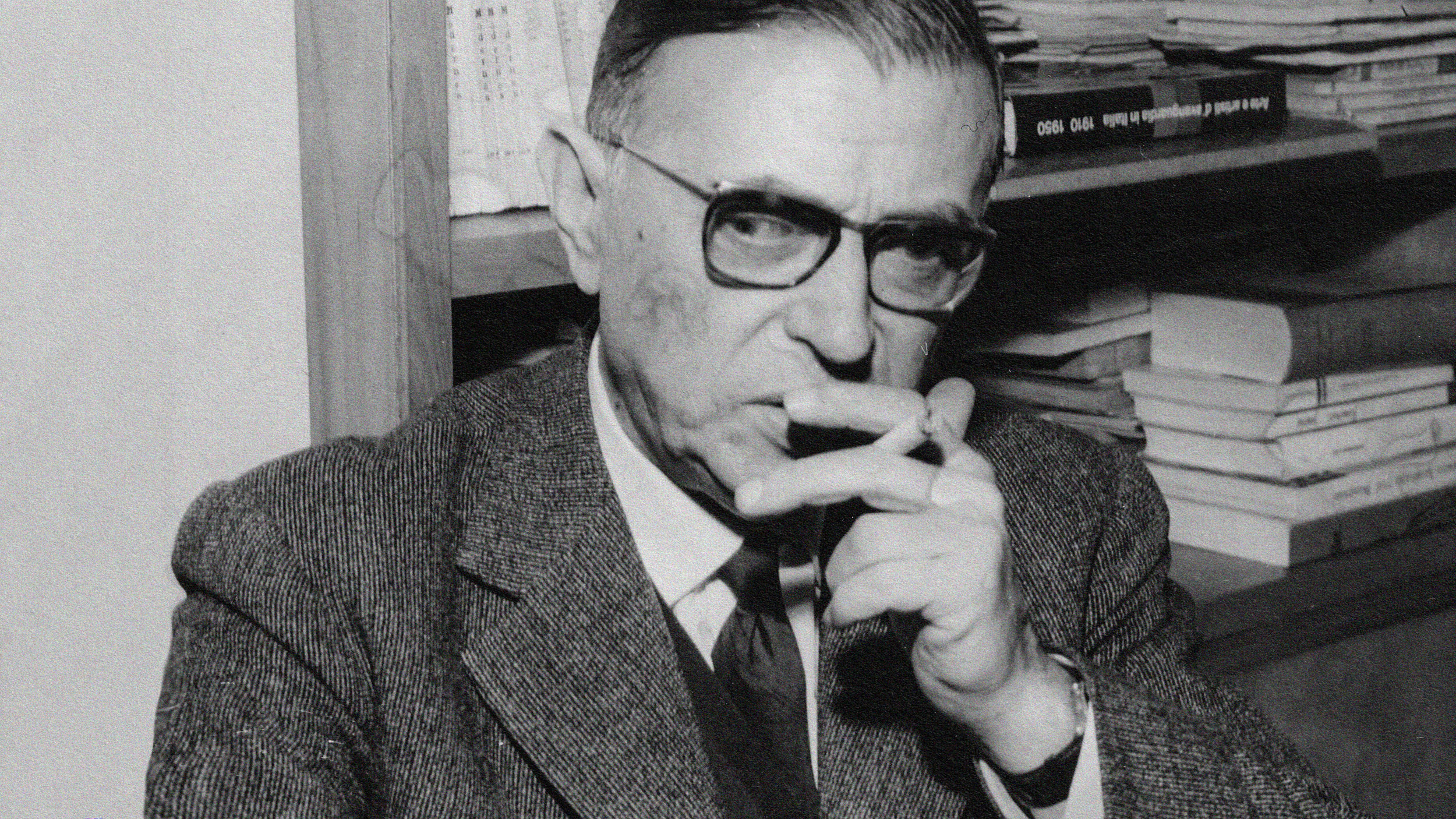

Bierce fought, and suffered injuries, in the gruesome Battle of Shiloh, an experience that some critics believe formed the nihilistic core of his comedy. Look into the eyes of the photo above: that is a man who’s seen some things. His influence on Vonnegut, witness to the Dresden massacre, becomes clearer in that light, though Bierce’s work is less tempered with the milk of human kindness.

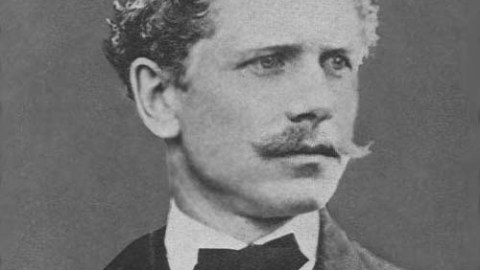

A reticent man in life, Bierce died as a total enigma: he disappeared in Mexico in 1913 while traveling—at age 71—with Pancho Villa’s army. As a result, he joins a select club of famous authors who have died or vanished under mysterious circumstances. Others include the poet Weldon Kees (probably a suicide; his car was found abandoned by the Golden Gate Bridge after he’d told a friend he was going to Mexico) and Poe and Christopher Marlowe, whose deaths are shrouded in suspicions of foul play. My personal theory is that all of these men are gathered on an island somewhere in the Twilight Zone, discussing literature and the virtues of terrible mustaches.