The More You Pay to Send your Children to School, the Fewer Days they Will Actually Be Educated

I’d like to get the Freakonomics guys to explain this paradox of K-12 education: The more money you spend for your children’s education, the fewer days they’ll actually be educated.

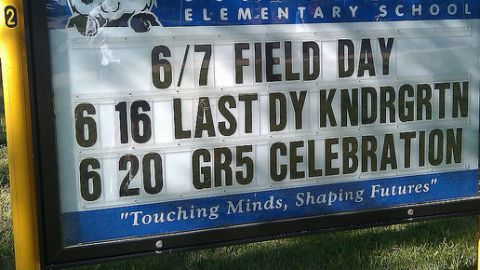

Baltimore City’s public schools, where I more or less happily attended school from kindergarten through 12th grade, keep children in school, typically, 18 days more than the private school where my husband and I pay steep tuition.

For all the purported failings of America’s public schools, which I believe are exaggerated, they manage to educate children for a longer chunk of the year.

A friend with children in two uber-elite private schools in Washington, DC reports that her situation is worse than in Baltimore. The schools routinely tag on extra days to Federal holidays (“Where are you vacationing for the extended Arbor Day weekend,” I can imagine well-heeled parents saying).

Like farmers who are paid not to grow soybeans, we pay exorbitantly for our children not to go to school.

The informal calendar reinforces the rule. Tuition-charging schools are notoriously trigger-happy with the snow days, and they spend a great deal of time ramping up and down, at the beginning and the end of the year. They ease in to the already-tardy school year, so that the reappearance of schoolwork doesn’t shock the system. Then they ease down, weeks before the school year officially ends.

During the wind up and wind down phases, you’re likely to get lots of requests for party materials. In the last three weeks alone I’ve gotten requests for volunteers for an ice cream social to end the school year, a snack (non-peanut based) to share at a sub-party in music class, a request that I bring a salty snack for the celebration of the children’s work party, and an invitation to a “Spring Sing” (twin to the “Winter Sing”) and a play to dramatize Greek myths. Then there’s the final convocation of the school year, in which the children will sing “Lean on Me,” the rehearsal of which probably chewed up a good hour of math time but I’m afraid to ask.

It sounds like school-as-summer-camp.

Math and Language Arts are suspended for every minute spent partying and riding wave after cresting wave of a sugar high at events ironically conceived as winding-down occasions. One classmate of my son’s ate so much sugar—naturally enough, since he’d attended two in-school parties that day—that he threw up and had to go home early (thereby missing another party, I imagine).

A friend who teaches valiantly in a Baltimore City public school notes the contrast that she “teaches until the very last day, in a non-air conditioned classroom.”

I know. I’m a crank. I’m the Grinch who Stole the 19th Ice Cream Social.

I adore Butt in Chair learning, and don’t see it as the least bit incompatible with the creative process, or even with fun. I like the grind.

There’s this illusion that creativity of any kind is epiphanal. But in many cases the epiphany is simply the end-stage and culmination of years of prior grind work and thought.

A hundred years ago the worst thing that could befall a child was idleness and insolence. Today, the worst thing seems to be boredom or bad self-esteem.

As for our short-sheeted school year, the National Summer Learning Association is on the case. They’ve recommended year-round schooling, with nice long breaks in the summer and winter.

It makes so much sense. The summer brain drain is bad enough with privileged children, who can afford interesting summer activities, but it’s even worse with less advantaged children, whose parents can’t afford to supplement the school year learning with weeks of expensive camps or courses.

The extended summer break is an historical anachronism a few times over. It’s an anachronism of the agrarian calendar, when children were required to help their parents seasonally with crops.

It’s also a vestige of the days when a full-time, non-wage earning, stay at home, middle-class mother could look after her children for the entire summer without the expense of nannies or summer camps. There seems to be some fantasy at play that we’re all whisking off to cottages in Maine for the summer, that murky business of Earning a Living conveniently off-stage somewhere.

And, the school calendar is a sad vestige of a poignant era, by now endangered if not downright extinct, when children in elementary school were allowed to play on their own all day long outdoors, in open spaces, without parental anxiety and fear.

The upshot is that we’ve got an asynchronous school calendar from Little House on the Prairie in the age of The Matrix, when most of us have only visited a farm once or twice, wouldn’t know the working end of a cow, and work in cubicles—all year long, come rain… or shine… or Dunkin Donut-crazed class party.