Book Review: The Swerve

Summary: The compelling true story of the Renaissance humanists who rescued Greek and Roman philosophy from oblivion and wrenched the Western world out of the Dark Ages.

After the collapse of the Roman empire, Europe descended into a centuries-long era of cultural and intellectual stagnation, a dark age of theocracy and feudalism. But how did the Western world pull itself out of this pit? What brought about the rekindling of light and reason in the Renaissance? That question is the subject of Stephen Greenblatt’s Pulitzer Prize-winning history, The Swerve.

Greenblatt’s story has two heroes, one of whom bore the unlikely name of Poggio Bracciolini. Born in Tuscany in the 14th century, he was a scholar and a copyist, known for his excellent handwriting and his encyclopedic knowledge of Latin. Both these skills made him ideally suited for the job he spent most of his life at: working in the Vatican as an apostolic secretary, transcribing the official decrees and diplomatic correspondence for a succession of popes. But despite his employment in the heart of Christianity’s worldly empire, Bracciolini wasn’t a pious believer, but a rational humanist. His greatest passion wasn’t the sanguine myths of Christianity, but the poetry, literature and philosophy of vanished Rome.

By his day, that empire was little more than ruins and faded memories: many once-great Roman cities had become decaying hovels where people scavenged for usable stone and metal [p.156]. The writings of its great citizens and thinkers survived only in monastic libraries, where monks copied them not to learn from them or preserve them, but as a deliberately tedious exercise in drudgery meant to instill spiritual discipline [p.37]. Many were lost to the ravages of time: water damage, fire, mold, insects, gnawing rodents. Others were deliberately destroyed, the ancient ink scraped away so that the valuable parchment could be reused to copy the text of the Bible or the writings of theologians.

Poggio was part of a growing circle of early Renaissance book-hunters who fanned out across Europe, looking for forgotten books in isolated monasteries, hoping to copy them and rescue them from oblivion. And his single greatest discovery was Greenblatt’s other hero, a Roman by the name of Titus Lucretius Carus, who lived around 50 BCE.

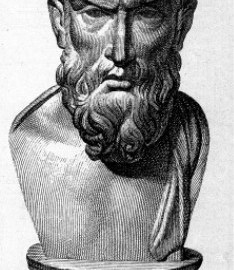

About Lucretius himself we know virtually nothing. (Christian church fathers claimed he went mad and committed suicide [p.53], but that’s almost certainly polemical slander.) But what we do have is his greatest work, an epic six-book poem called De rerum natura, which is Latin for “On the Nature of Things”. In it, Lucretius lays out a worldview derived from the teachings of his philosophical idol, the Greek thinker Epicurus.

In Epicurus’ view, the only fundamental components of existence are the atoms: discrete, indestructible, invisibly tiny particles that combine in a vast diversity of patterns to form everything that exists in the universe, from planets to human beings. In a startling anticipation of quantum mechanics, Epicurus even claimed that atoms could exhibit “random swerves”, introducing an element of indeterminacy and chance to the universe.

But what made Epicurean thinking so dangerous to orthodoxy was its thoroughgoing religious skepticism. It teaches that all religions are superstitions born of fear and ignorance: natural forces govern all that occurs, there are no gods that care about our fates or punish us for our sins, and human beings, being made of atoms like everything else, have no immortal souls that survive the deaths of our bodies. According to Epicurus, recognizing and accepting this truth would bring a sense of wonder and serenity, and would free us to live lives devoted to happiness and pleasure. (Epicureanism is often erroneously treated as synonymous with gluttony and indulgence, but in fact Epicurus and Lucretius themselves refuted this: their real view, similar in some respects to Buddhism, counseled moderation and contentment rather than chasing after extravagance.)

Naturally, to the early Christian church, Epicurean philosophy was the most detestable of heresies. And when it came wrapped in Lucretius’ intensely beautiful and seductive Latin poetry, which was acknowledged as a masterwork even by his rhetorical opponents, it was more dangerous still. It was only by a quirk of chance – a swerve – that this ancient epic didn’t vanish from human knowledge entirely. It’s not even clear that Poggio and his humanist contemporaries recognized the full implications of unleashing it again on the world, but unleash it they did, and civilization is still grappling with the fallout. One could make the case that the family tree of Western skepticism and empiricism, from David Hume onwards, owes a huge debt to the Epicurean ideas that survived the centuries, like a storm-tossed bit of driftwood that took root on a new shore and burst into bloom.

Greenblatt tells this story against the turbulent backdrop of early-Renaissance Europe, where city-states and nations were jousting for power while poets and antiquarians dreamed of the vanished glories of Rome. The Catholic church, thoroughly corrupt and obscenely wealthy, cast a shadow over all else: although the Protestant Reformation hadn’t fully erupted, there were already rumblings of dissent which it tried its utmost to suppress (one disgraceful chapter he chronicles was the betrayal and execution of the reformer Jan Hus). At one point, there were three self-proclaimed popes squabbling with each other, an amusing episode that Greenblatt tells with skill. The Swerve is an excellent account of how the modern world emerged from this cauldron, and a book that’s well worth every freethinker’s time.

Image credit: Bust of Epicurus, via Wikimedia Commons

Daylight Atheism: The Book is now available! Click here for reviews and ordering information.