How To Avoid Your Own Brain’s Biases

Thinking, like seeing, has built-in blind spots. An old parable and Husserl’s matchbox can illuminate these geometric, biological, and cognitive limits. We can’t evade their unseen dangers unaided.

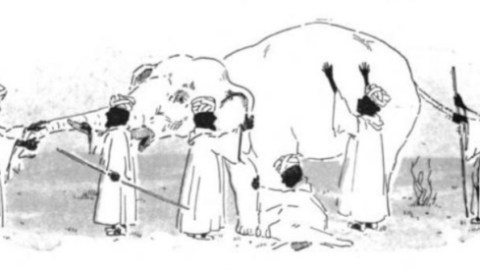

In the parable six blind men try to describe an elephant they’re standing beside. Feeling what’s in front of him, each has “direct” evidence that it’s a snake, spear, fan, tree, wall, or rope (details vary). But only combining perspectives gives the whole picture.

Perspective also constrains the sighted, as Edmund Husserl demonstrated using a matchbox: geometry ensures only three sides are visible at a time. In Husserl’s philosophy, all experience is embodied, and knowledge is prone to bodily perspective limits. Assumptions also limit and frame thinking, they’re the mental version of line of sight, and can cause “theory-induced blindness.”

While reading this, you are actively ignoring another optical limitation Evolution gave our eyes blind spots (there are no light receptors where the optic nerve connects to the retina). These blind spots are invisible because our brains evolved to concoct a continuous visual field.

The brain has its own blind spots, but “cognitive biases” are often misunderstood. Take Ezra Klein’s article on “identity-protective cognition” research which he says “tells us we can’t trust our own reason.” He seems surprised that our thinking is biased to protect our self-image and peer-image. Isn’t the brain’s primary mission protecting its owner? We all have that bias, and we’re all prone to others.

Here’s the needed logic: Since all human brains have biases that they’re unaware of, mine must also. However certain I feel about an issue, it’s irrational to ignore the potential influence of my own biases. Reason dictates using assisted thinking. This is old wisdom, as the Bible asks, “Who can discern their own errors?” Shakespeare laments, “O that you could turn your eyes toward the napes of your necks, and make but an interior survey.”

Barring rare geniuses, we often don’t think well alone. But two heads are better only if, like two eyes, they have different perspectives. Gerrymandering your mind by consulting only the like-minded doesn’t balance biases, it reinforces them. Constructive co-thinking requires diversity.

An identity too many thinkers seek to protect is that of the all-seeing, all-knowing intellectual gladiator. Debate is framed as combat which distorts the objective to winning, not improving ideas. Framing as a conversion or a building project is better. Conversations are enriched by differences. And good building projects require the best materials from any source.

A basic cognitive geometry applies: Unless what you’re pondering is small or well understood, multiple vantage points are advantageous. Truth usually has multiple paths, it’s safely approachable from different assumptions. The wise seek bias-balancing heterospective (other-view-ness). It’s the only cure for known unseeables.

Illustration, public domain, via WikiMedia Commons