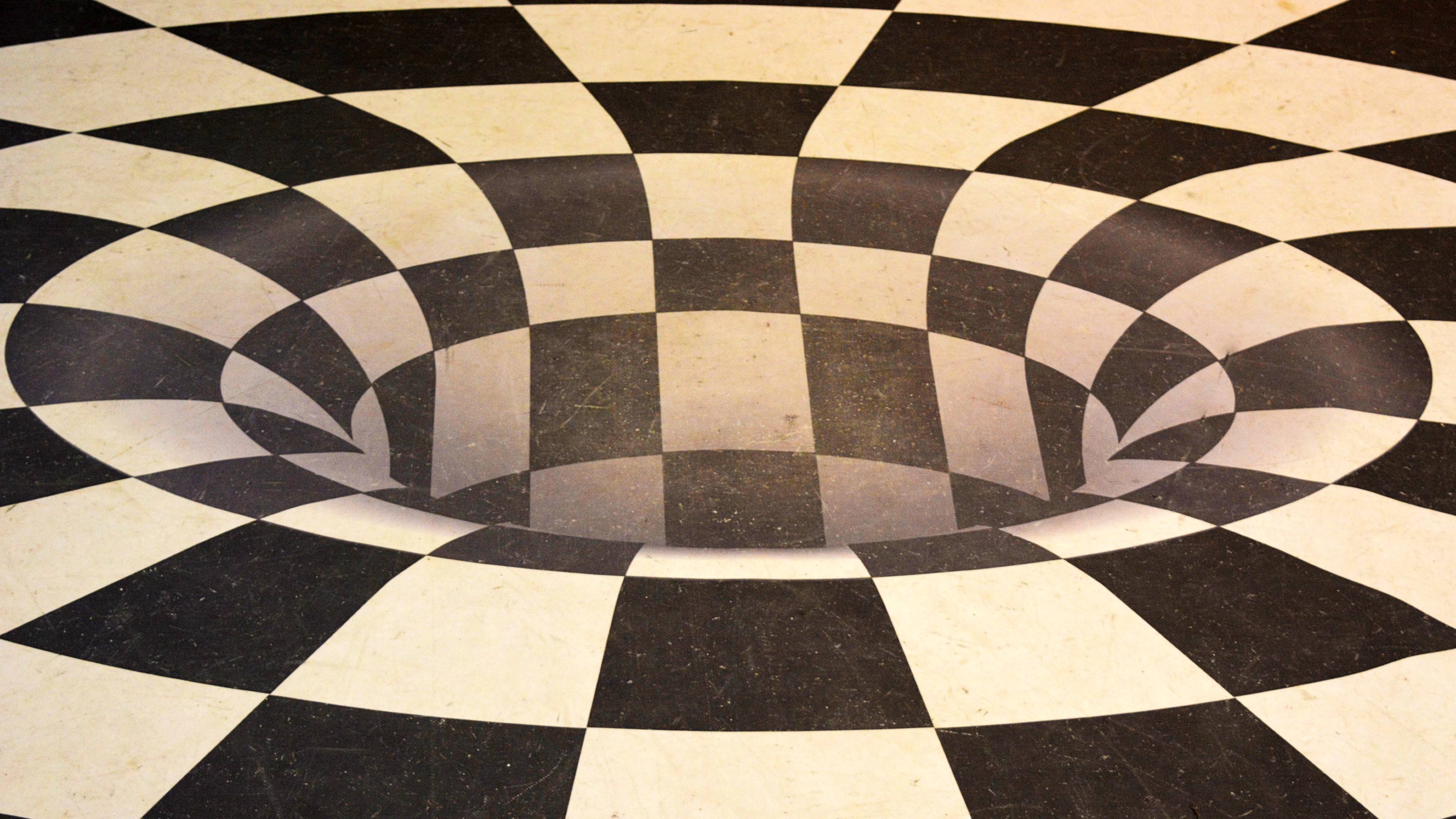

Are you actually in the driver’s seat of your own life? The illusion of free will says that our choices are determined by factors greater than our intentions and actions, that total conscious control is purely an illusion.

We may assume that illusions like this have evolved for their usefulness, but most illusions that we experience are actually glitches, says bestselling author Annaka Harris. Take for example the illusion of self – the other side of the illusion of free will coin.

We think of ourselves as solid, unchanging entities that move through time and space, separate from the rest of the physical world. This illusion confuses us about our place in nature, and the state of our reality.

Harris explores these two illusions and how they shape our everyday experience.

ANNAKA HARRIS: People often think that illusions are evolved for their usefulness, but the truth is that most illusions that we experience are actually glitches. One example of this is the illusion of self and the illusion of free will, and the illusion of free will and self are really two sides of the same coin. It's this experience we all have of being a solid entity, an unchanging entity that moves through time, that is somehow living somewhere inside my body. It's my body, it's my brain, and therefore, somehow separate from the physical world, and this illusion confuses us about our place in nature and the state of reality on on many different levels. But the truth is that there really is this positive way to view it. So I think that free will, for the most part, is an illusion. But when I talk about free will, I like to distinguish between conscious will and free will. So I use the term free will to talk about decision-making processes in nature, which there clearly are. If you look at something like a pea tendril, when it senses that it's close to a branch that it can wrap itself around, it starts growing more quickly in that direction, and then it changes the growth, so that it wraps itself around a branch. Most of us wouldn't consider that to be a free decision-making process. It's a cause and effect process that occurs in nature. And as you move up in complexity to the level of brains and then human brains, the number of factors that come into play are so expansive that it would be impossible for us to track them all. But it is a process, and it's a process by which the brain is interacting with the exterior world and measuring the different outcomes of the different possible futures, and then ultimately making a decision. This is something that I think we can refer to as free will, and that what many people mean by free will. The problem with having "free" in the title is that it's not free in the way we feel it is, and this is where the illusion comes in. We begin with this illusion of self, of being this solid, concrete entity that lives somewhere in the head, and even though we know better, feels as though it's separate from the physical world and separate from the cause-effect relationships that we know to be in place that could somehow freely make a decision, or freely intervene in the physical world outside of the relationships of cause and effect. And because everything we experience, everything we know takes place within this felt experience of consciousness, we often equate this feeling of self with consciousness, and that I think is clearly an illusion, and I call that conscious will because it is this feeling that my conscious experience is this self and is the thing that has this freedom, and this is how the illusion of self and the illusion of free will are related. There was a very interesting study done in 2013 in which they put participants in an fMRI machine and showed them a screen, and presented two numbers on that screen, and they gave them the option of either adding or subtracting these two numbers, and they were scanning the activity of these participants' brains while they were doing this calculation, and the result of this study was that the experimenters could tell up to four seconds not only when this person was going to make the decision, but whether they decided to add or subtract, and so you get the sense viscerally that there's no self or free will making decisions behind the scenes, but that in terms of your conscious experience, a decision really arises. So when I talk about the illusion of self, this is often very hard for people to grasp what that could even mean, and so I'd first like to just be very clear about what I'm not talking about when I talk about the illusion of self. So what is not an illusion is the fact that we are organisms and systems in nature, and that we have certain tendencies, and that we're organized in a certain way, and so we can talk about ourselves in the same way that we can talk about a cat as another organism in nature, or even an ocean wave. But even though we can label it a wave and we can call it a wave and talk about the types of things waves do, we all understand that a wave is not a static thing in nature. It's a process, and our brains are very much the same thing. They are processes in nature that are ever-changing, ever-evolving, that we are in constant communication with the external world, and that the boundaries between ourselves and the world and ourselves and each other are not as solid and firm as they appear to us or that they feel to us to be, especially when we feel like a static self. So the neuroscience is really still in its infancy, but we're starting to learn more and more about how this illusion of self gets created. Part of it has to do with something called change blindness, which we know about in vision. We have a blind spot in our visual field that we are not conscious of, that we don't detect, and neuroscientists are just now starting to understand that there is a change blindness with respect to our experience over time, so that we don't notice how different each of our experiences in every moment are from every other, which adds to this illusion of being a solid entity that moves through time unchanged, and we also know that memory plays a role in creating this experience of self as well. There's a sense in which all of the memories that we have access to over time were being experienced by the same subject, and you can imagine if your memories weren't strung together and your experience was just of each present moment, there'd be much less of a sense of a self moving through time. We're also learning a little bit more about what neuroscientists refer to as the default mode network. So we know that when the default mode network is active, we are highly aware of this illusion of self, and it tends to quiet down when we're experiencing what people talk about as a flow state. So when we're very immersed in our work, if we're very immersed in a sport, when people are under the influence of some psychedelic substances, or various meditation techniques that quiet down the default mode network, we are not so aware of self versus other or self versus world, which is actually closer to the underlying reality. So many people find this realization to be quite disconcerting, which is understandable, and I think one way to address that is levels of usefulness. The vast majority of the time, it is not useful or helpful to realize that there's an illusion of sorts taking place. One example I like to give is that we more or less walk around with the illusion that the Earth is flat, and we act as though the Earth is flat, and that's the best way to go about our everyday lives. If we constantly reminded ourselves that the Earth is a sphere, and had to keep that in mind, and had to feel that way everywhere we went, it would just be an annoying distraction, and would get in the way of all kinds of activities and would not be helpful. And the same is true of the illusion of self and the illusion of free will. There are places where it's useful. It's useful, obviously, for the sciences and for neuroscience, but it actually can also be useful psychologically in certain circumstances, and again, this isn't something you wanna remind yourself of in every moment, but there are moments where realizing that there's an experience of conscious will taking place can be quite liberating. Many people get stuck in feeling responsible for their psychological state, and there's a way in which simply being with whatever uncomfortable emotions you're experiencing, whether it's sadness or frustration or anger, being with them rather than believing that you are controlling them can be extremely beneficial for psychological wellbeing. There are also ways that we can apply this in our relationships with other people. I sometimes talk about the fact that you would never get angry at a tornado, and that doesn't mean anger doesn't have a place in society and culture. But there are times when anger can overcome us and start to rule our lives in a way that is incredibly unhelpful and unhealthy, and when we understand that our brains are essentially processes playing out in nature, and there isn't a solid self to every person that is somehow evil or worthy of blame can also be liberating to notice in certain circumstances.