Why the number “1/137” appears everywhere in nature

- When we think of fundamental constants, we often think of things like the speed of light, the strength of the force of gravity, or the electric charge of the electron.

- Those constants, however, are all dimensionful; they depend on the units we choose to measure the Universe. An alternative is to use dimensionless constants: pure numbers, alone, with no units at all.

- When we do, we run into a completely fascinating one: the fine-structure constant, which represents the strength of the electromagnetic force. Here’s why it, and the number 1/137, matters.

There’s an enormous existential question that we’ve wondered about ever since we first realized that the Universe does, in fact, obey physical laws at all: why is our Universe the precise way it is, rather than any other way we could’ve imagined? There are only three things that make it so:

- the laws of nature themselves,

- the fundamental constants governing reality,

- and the initial conditions that our Universe was born with.

If our Universe had different laws of nature, then all bets would be off; the cosmos would have been vastly different in almost any way you can fathom. Protons might decay, fundamental quantities like particle masses might not be constant, and the strengths of any fundamental forces might joltingly change at any moment.

If only the initial conditions of our Universe were different, the way the cosmic story unfolded would be the same in terms of broad strokes, but the details would differ between that hypothetical Universe and our own. But for the fundamental constants, some changes would be profound, while others would be barely noticeable. In our own Universe, the constants have the explicit values they do, and that specific combination yields the life-friendly cosmos we inhabit. One of those fundamental constants is known as the fine structure constant, and its approximate value (1/137) appears in calculations that matter for a whole host of phenomena, on subatomic and cosmic levels both.

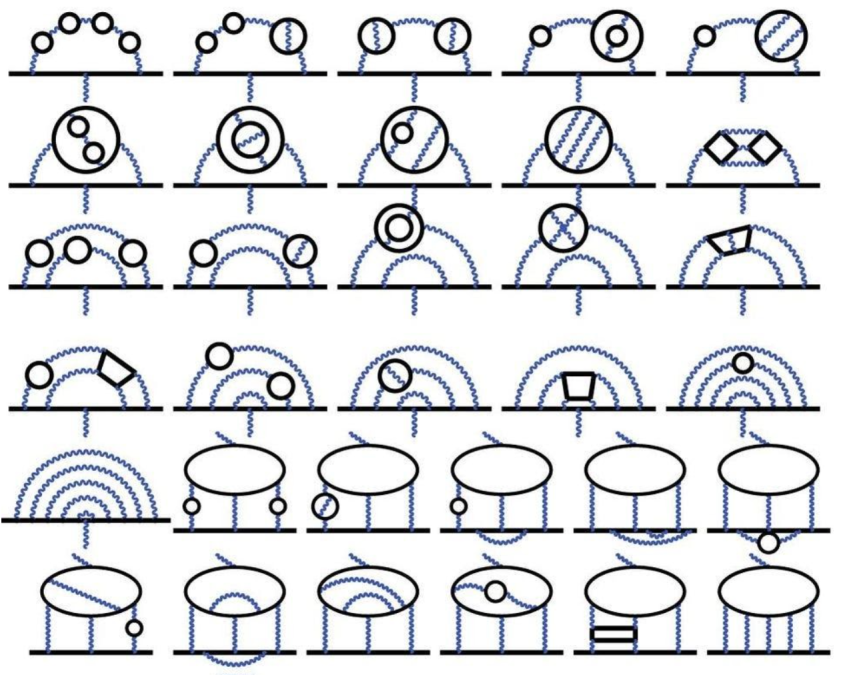

Our story begins with the simple building blocks of matter that make up the Universe: the fundamental particles of the Standard Model.

Credit: APS/Alan Stonebraker

Our Universe, if we break it down into its smallest constituent parts, is made up of the particles of the Standard Model. Quarks and gluons, two types of these particles, bind together to form bound states like the proton and neutron, which themselves bind together into atomic nuclei. Electrons, another type of fundamental particle, are the lightest of the charged leptons. When electrons and atomic nuclei bind together, they form atoms: the building blocks of the normal matter that makes up everything in our day-to-day experience.

Before humans even recognized how atoms were structured, we had determined many of their properties. In the 19th century, we discovered that the electric charge of the nucleus determined an atom’s chemical properties, and found out that every atom had its own unique spectrum of lines that it could emit and absorb. Experimentally, the evidence for a discrete, quantum Universe was known long before theorists put it all together.

Credit: N.A.Sharp, NOAO/NSO/Kitt Peak FTS/AURA/NSF

In 1912, Niels Bohr proposed his now-famous model of the atom, where the electrons orbited around the atomic nucleus like planets orbited the Sun. The big difference between Bohr’s model and our Solar System, though, was that there were only certain particular states that were allowed for the atom, whereas planets could orbit with any combination of speed and radius that led to a stable orbit.

Bohr recognized that the electron and nucleus were both very small, had opposite charges, and knew that the nucleus had practically all of the mass. His groundbreaking contribution was understanding that electrons can only occupy certain energy levels, which he termed “atomic orbitals.” The electron can orbit the nucleus only with particular properties, leading to the absorption and emission lines characteristic to each individual atom.

This model, as brilliant and clever as it is, immediately failed to reproduce the decades-old experimental results from the 19th century. All the way back in 1887, Michelson and Morely had determined the atomic emission and absorption properties of hydrogen, and they didn’t quite match the predictions of the Bohr atom.

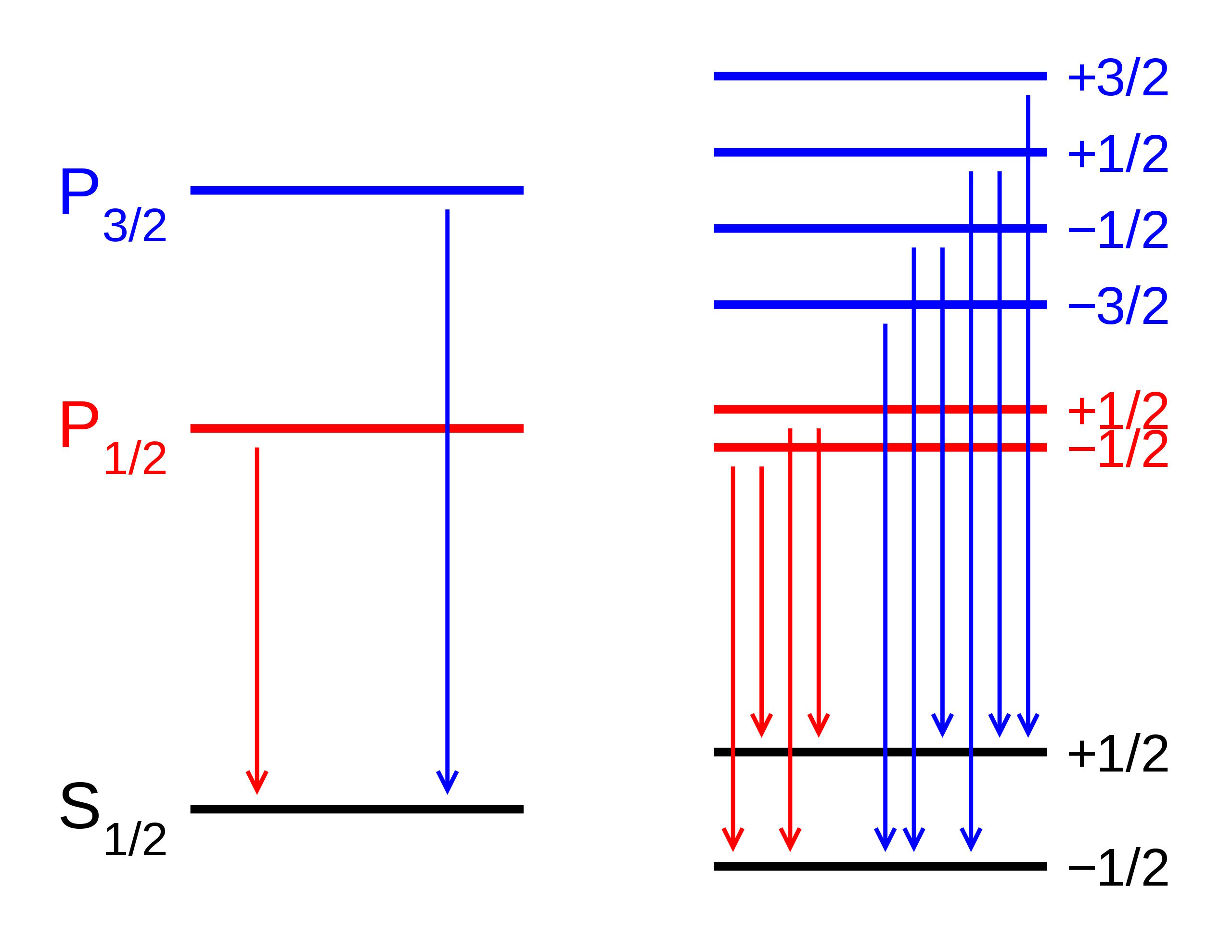

The same scientists who determined that there was no difference in the speed of light whether it moved with, against, or perpendicular to the motion of the Earth had also measured the spectral lines of hydrogen more precisely than anyone ever before. While the Bohr model came close, Michelson and Morely’s results demonstrated small shifts and extra energy states that departed slightly but significantly from Bohr’s predictions. In particular, there were some energy levels that appeared to split into two, whereas Bohr’s model only predicted one.

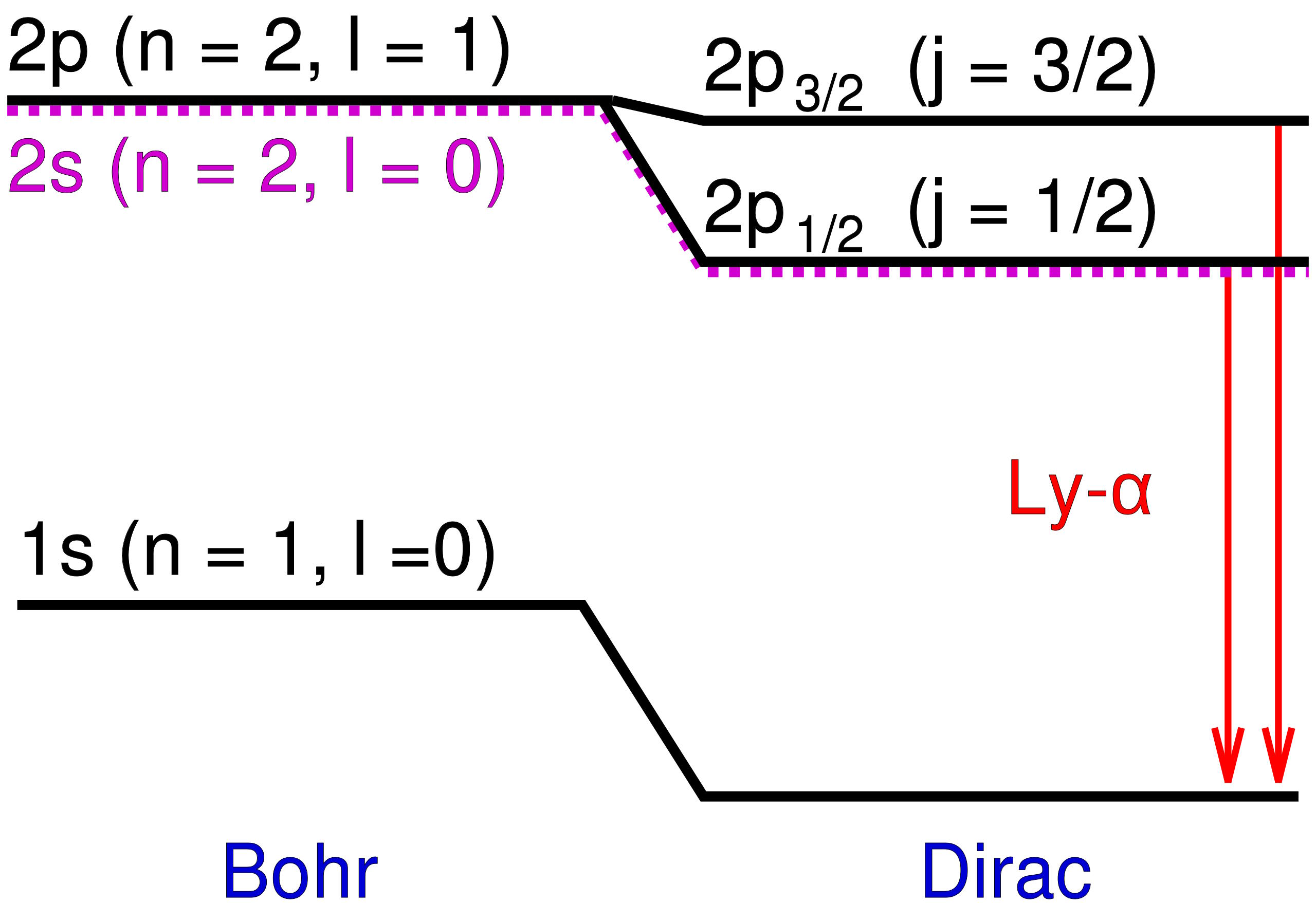

Those additional energy levels, which were very close to one another and also close to Bohr’s predictions, were the first evidence of what we now call the fine structure of atoms. Bohr’s model, which simplistically modeled electrons as charged, spinless particles orbiting the nucleus at speeds much lower than the speed of light, successfully explained the coarse structure of atoms, but not this additional fine structure.

That would require another advance, which came in 1916 when physicist Arnold Sommerfeld had a realization. If you modeled a hydrogen atom as Bohr did, but took the ratio of a ground-state electron’s velocity and compared it to the speed of light, you’d get a very specific value, which Sommerfeld called α: the fine structure constant. This constant, once folded into Bohr’s equations properly, was able to precisely account for the energy difference between the coarse and fine structure predictions.

In terms of the other constants known at the time, α = e²/(4πε_0)ħc, where:

- e is the electron’s charge,

- ε_0 is the electromagnetic constant for the permittivity of free space,

- ħ is Planck’s constant,

- and c is the speed of light.

Unlike these other constants, which have units associated with them, α is a truly dimensionless constant, which means it is simply a pure number, with no units associated with it at all. While the speed of light might be different if you measure it in meters per second, feet per year, miles per hour, or any other unit, α always has the same value. For this reason, it’s considered to be one of the fundamental constants that describes our Universe.

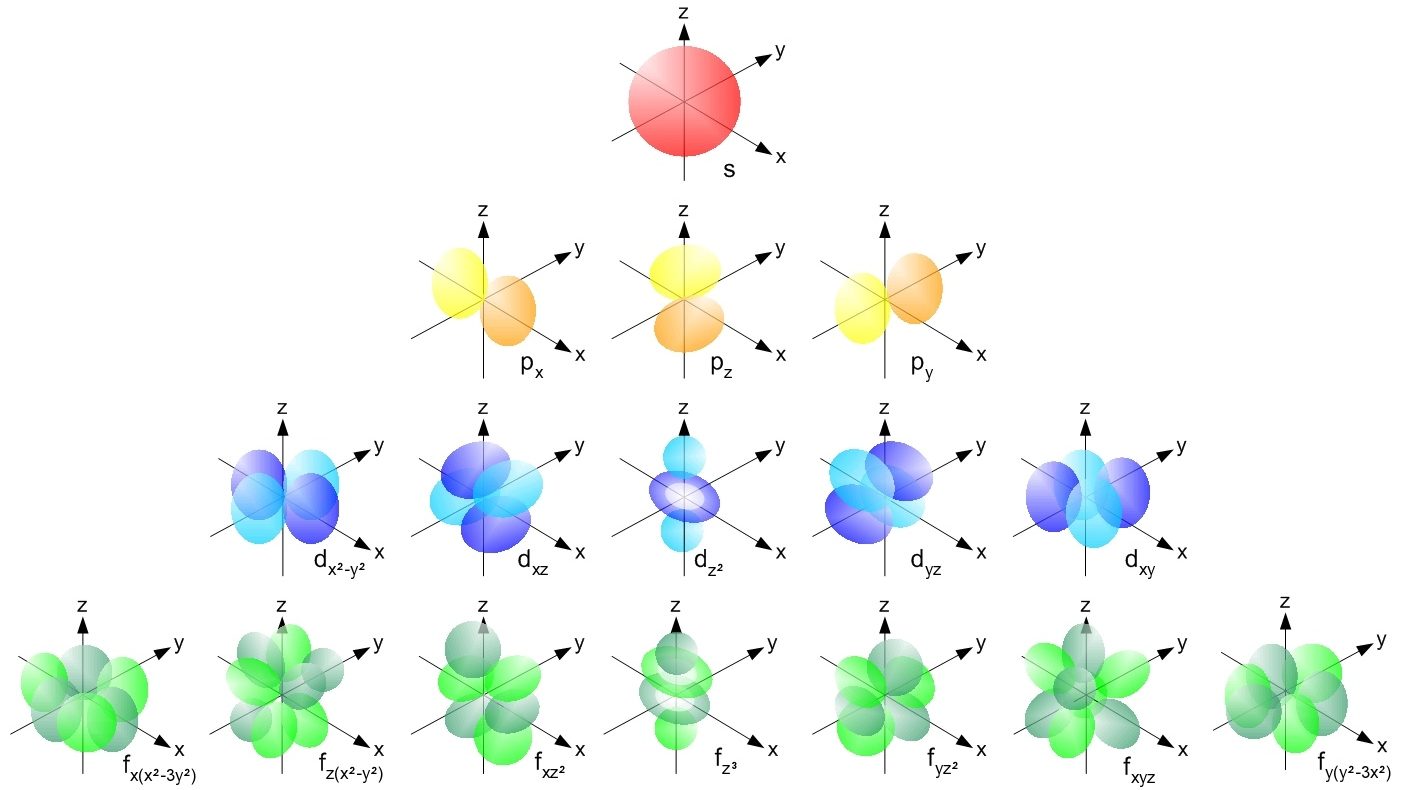

Credit: PoorLeno/Wikimedia Commons

An atom’s energy levels cannot be accounted for properly without including these fine structure effects, a fact which resurfaced a decade after Bohr when the Schrödinger equation came onto the scene. Just as the Bohr model failed to reproduce the hydrogen atom’s energy levels properly, so did the Schrödinger equation. It was quickly discovered that there were three reasons for this.

- The Schrödinger equation is fundamentally non-relativistic, but electrons and other quantum particles can move close to the speed of light, and that effect must be included.

- Electrons don’t simply orbit atoms, but they also have an intrinsic angular momentum inherent to them: spin, with a value of ħ/2, that can either be aligned or anti-aligned with the rest of the atom’s angular momentum.

- Electrons also exhibit an inherent set of quantum fluctuations to their motion, known as zitterbewegung; this also contributes to the fine structure of atoms.

When you include all of these effects, you can successfully reproduce both the gross and fine structure of matter.

The reason these corrections are so small is because the value of the fine structure constant, α, is also very small. According to our best modern measurements, the value of α = 0.007297352569, where only the last digit is uncertain. This is very close to being an exact number: α = 1/137. It was once considered possible that this exact figure could be accounted for somehow, but better theoretical and experimental research has demonstrated that the relation is inexact, and that α = 1/137.0359991, where again only the last digit is uncertain.

Credit: Tiltec/Wikimedia Commons

Even including all of these effects, though, doesn’t get you everything about atoms. Not only is there the coarse structure (from electrons orbiting a nucleus) and fine structure (from relativistic effects, the electron’s spin, and the electron’s quantum fluctuations), but there’s hyperfine structure: the interaction of the electron with the nuclear spin. The spin-flip transition of the hydrogen atom, for example, is the narrowest spectral line known in physics, and it’s due to this hyperfine effect that goes beyond even fine structure.

Credit: Ed Janssen/ESO

But the fine structure constant, α, is of tremendous interest to physics. Some have investigated whether it might not be perfectly constant. Various measurements have indicated, at various points in our scientific history, that α might either vary with time or from location to location in the Universe. Measurements of the spectral lines of hydrogen and deuterium, in some cases, have indicated that perhaps α changes by ~0.0001% through space or time.

These initial results, however, have failed to hold up to independent verification, and are treated as dubious by the greater physics community. If we did ever robustly observe such variation, it would teach us that something that we observe to be unchanging in the Universe — like the electron charge, Planck’s constant, or the speed of light — might actually not be a constant through space or time.

A different type of variation, though, has actually been reproduced: α changes as a function of the energy conditions under which you perform your experiments.

Let’s think about why this must be so by imagining a different way of looking at the fine structure of the Universe: take two electrons and hold them a specific distance apart from one another. The fine structure constant, α, can be thought of as the ratio between the energy needed to overcome the electrostatic repulsion driving these electrons apart and the energy of a single photon whose wavelength is 2π multiplied by the separation between those electrons.

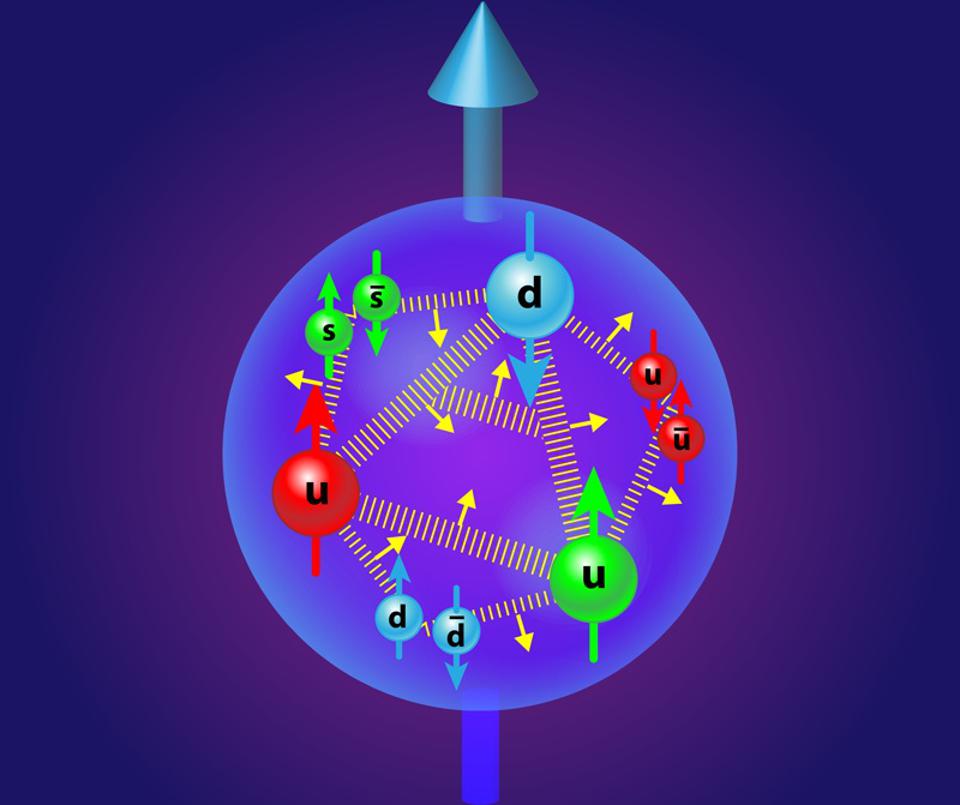

In a quantum Universe, though, there are always particle-antiparticle pairs (or quantum fluctuations) that populate even completely empty space. At higher energies, this changes the strength of the electrostatic repulsion between two electrons.

Credit: Derek B. Leinweber

The reason why is actually straightforward: the lightest charged particles in the Standard Model are electrons and positrons, and at low energies, the virtual contributions from electron-positron pairs are the only quantum effects that matter in terms of the strength of the electrostatic force. But at higher energies, it not only becomes easier to make electron-positron pairs, giving you a larger contribution, but you start getting additional contributions from heavier particle-antiparticle combinations.

At the (mundane) low energies we have in our Universe today, α is approximately 1/137. But at the electroweak scale, where you find the heaviest particles like the W, Z, Higgs boson and top quark, α is somewhat greater: more like 1/128. Effectively, owing to these quantum contributions, it’s as though the electron’s charge increases in strength.

Credit: T. Aoyama et al., Phys. Rev. Lett., 2012

The fine structure constant, α, also plays a major role in one of the most important experiments going on in modern physics today: the effort to measure the intrinsic magnetic moment of fundamental particles. For a point particle like the electron or muon, there are only a few things that determine its magnetic moment:

- the electric charge of the particle (which it’s directly proportional to),

- the spin of the particle (which it’s directly proportional to),

- the mass of the particle (which it’s inversely proportional to),

- and a constant, known as g, which is a purely quantum mechanical effect.

While the first three are exquisitely known, g is only known to a little better than one part per billion. That might sound like a supremely good measurement, but we’re attempting to measure it to an even greater precision for a very good reason.

Back in 1930, we thought that g would be 2, exactly, as derived by Dirac. But that ignores the quantum exchange of particles (or the contribution of loop diagrams), which only begins to show up in quantum field theory. The first-order correction was derived by Julian Schwinger in 1948, who states that g = 2 + α/π. As of today, we’ve computed all the contributions to 5th order, meaning we know all of the (α/π) terms, plus the (α/π)², (α/π)³, (α/π)⁴, and (α/π)⁵ terms.

We can measure g experimentally and calculate it theoretically, and what we find, very curiously, is that the match between the two is very close, but not perfect. The differences between g from experiment and theory are very, very small: 0.0000000052, with an uncertainty of around ±0.0000000010: a 5.2-sigma difference. However, a second theoretical method yields a much smaller difference, suggesting that there may be some difficulty on the theory side; the experiments will certainly decide.

If there’s a true difference, we may be on the verge of new, beyond-the-Standard-Model physics; if not, we will learn something about our theoretical assumptions instead.

When we do our best to measure the Universe — to greater precisions, at higher energies, under extraordinary pressures, at lower temperatures, etc. — we often find details that are intricate, rich, and puzzling. It’s not the devil that’s in those details, though, but rather that’s where the deepest secrets of reality lie.

The particles in our Universe aren’t just points that attract, repel, and bind together with one another; they interact through every subtle means that the laws of nature permit. As we reach greater precisions in our measurements, we start uncovering these subtle effects, including intricacies to the structure of matter that are easy to miss at low precisions. Fine structure is a vital part of that, but learning where even our best predictions of fine structure break down might be where the next great revolution in particle physics comes from. Doing the right experiment is the only way we’ll ever know.

Ethan is on vacation this week. Please enjoy this article from the Starts With A Bang archives!