This fungus is so humongous that it can be mapped

- Somewhere in Oregon lives a mushroom that may be the largest, oldest, and heaviest living thing on Earth.

- Disappointingly, this giant lives mainly underground — but you can see its handiwork: dead trees, lots of them.

- The stats are impressive. The shroom weighs as much as 60 Boeing 747s and is five times the size of Monaco.

Deep in the Blue Mountains of Oregon lives what is possibly the largest, oldest, and heaviest living thing on Earth: a giant mushroom dubbed the Humongous Fungus.

The word “possibly” didn’t weasel its way into the previous sentence by accident. Estimates of this organism’s extent, age, and weight vary hugely. On either end of the scale, though, the numbers are impressive.

Twice as old as Stonehenge

Based on various appraisals of its growth rate, the enormous shroom that’s slowly consuming thousands of trees in the mountains a few miles east of Prairie City (population: 800) could be anywhere between 2,400 and 8,600 years old. The earlier date would make it twice as old as Stonehenge. The later one would merely make it a contemporary of Plato.

The weight of this mainly subterranean monster fungus could be as low as a few thousand, and as high as 27,000 metric tons. That’s close to 30,000 U.S. tons — or, to translate that into something easier to picture, about 60 Boeing 747s at maximum takeoff weight (444 metric tons each).

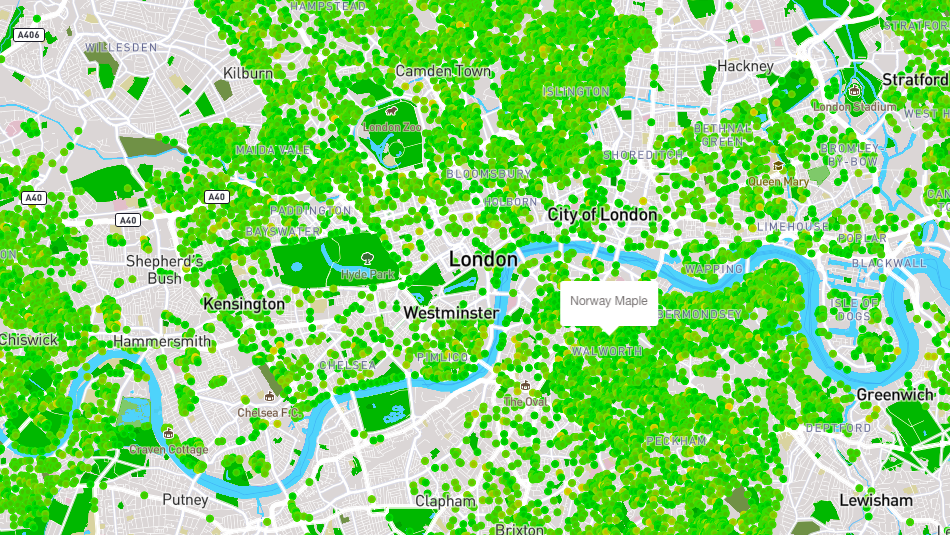

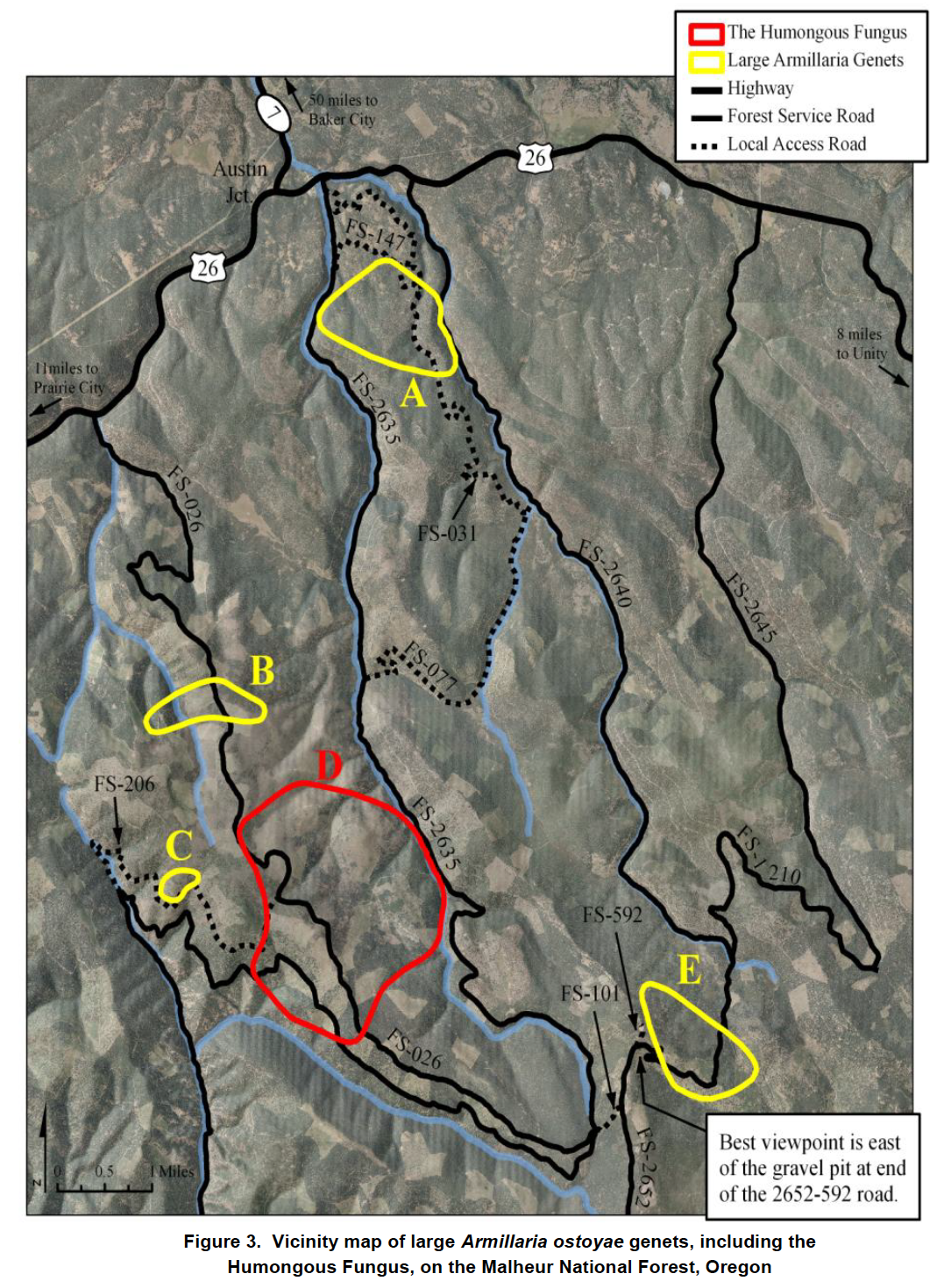

Perhaps the most spectacular measure of this creature’s immensity is the one with the smallest estimated variation: its size. This subterranean monster fungus covers an area between 3.5 and 3.7 square miles, or roughly 9 to 10 km2. That’s about five times the size of Monaco, the world’s second-smallest country. Like a yo mama joke come to life, that’s large enough to be clearly visible on a map — like this one.

The map, which shows the Reynolds Creek and Clear Creek areas in the northeastern part of the Malheur National Forest, also indicates the Humongous Fungus is not alone. It’s marked in red and labeled “D,” surrounded by four other giant fungi, marked in yellow and labeled A, B, C, and E.

Sounds like “Janet”

All belong to the same species: Armillaria ostoyae, a fungus known for its seasonal sprouting of honey mushrooms. However, each of those giant fungi is a genetically unique entity, or to use the proper term, a “genet” (pronounced like “Janet”).

That word describes a fungal colony developing from a common mycelium — the network of underground threads that helps fungi grow and spread. Because the individual fungi, which typically fruit on rotting trees, develop through cloning, they are genetically identical, meaning the entire genet can be considered one organism.

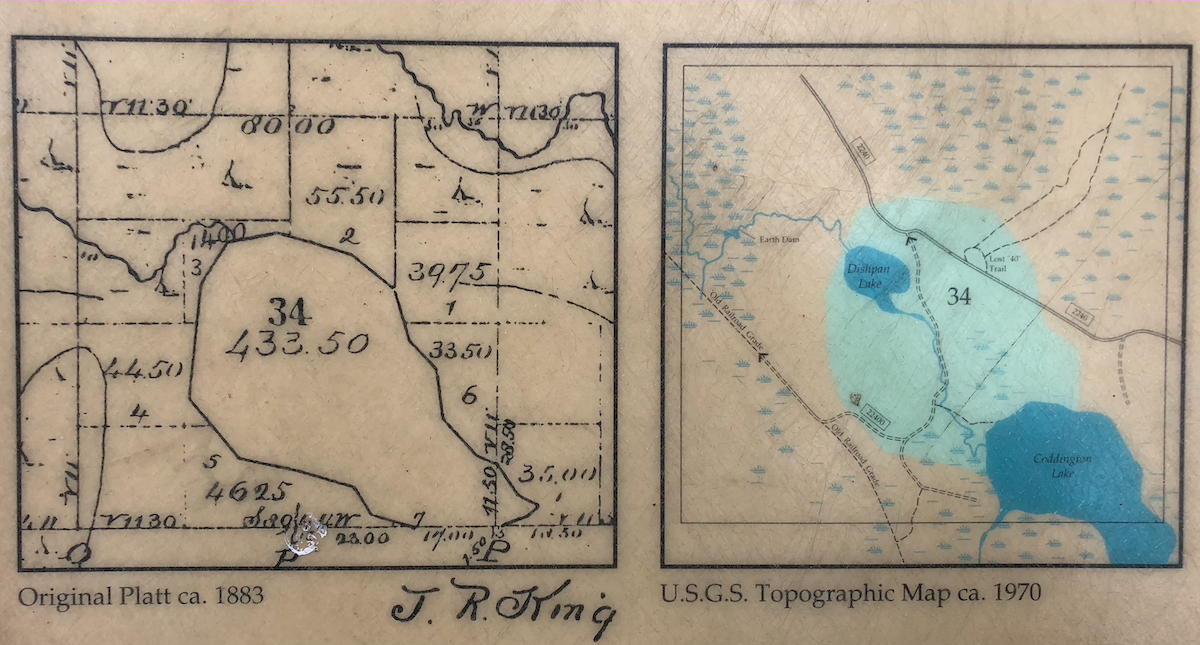

As the largest known individual fungus in the world, Genet D has rightly earned its nickname. But it’s not the first known “humongous fungus.” That credit goes to another fungal colony, discovered in 1992 in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Molecular geneticists discovered that the underground mycelia of the species Armillaria gallica, another variety of honey mushroom, covered 37 acres (0.15 km2), weighed 100 metric tons, and was around 1,500 years old.

World’s largest mushroom pizza

Those awesome figures inspired the nickname — and the local Chamber of Commerce. This August, the Upper Peninsula town of Crystal Falls celebrated its 33rd annual Humongous Fungus Fest, a celebration that occasionally features, among many other delights, what is claimed to be the world’s largest mushroom pizza, measuring 10 by 10 feet in at least one edition of the festival.

Resampling between 2015 and 2017 of the fungal colony in the Upper Peninsula has upped the estimates for Michigan’s giant fungus to 173 acres (0.7 km2) and 2,500 years. That’s both bigger than the Vatican and older than the Church, weighing some 400 metric tons.

Magnificent, but not magnificent enough. By that time, the “humongous” moniker had migrated to the West Coast, where Humongous Fungus II was discovered in 1998. A team of forestry scientists had set out to map the local spread of a tree-killing fungus in the Malheur National Forest, finding, to their surprise, that they couldn’t find its edge.

When they did, it turned out that this one was even larger than its Michigan counterpart, and since “humongous fungus” is so much more fun to say than its official name, “Genet D,” the name stuck.

So, who exactly is this voracious eater of Oregon forests? Its scientific name is Armillaria ostoyae, but it’s also known as the “shoestring fungus” for the long, thin, black strands called rhizomorphs that spread through the soil, infecting and killing tree roots.

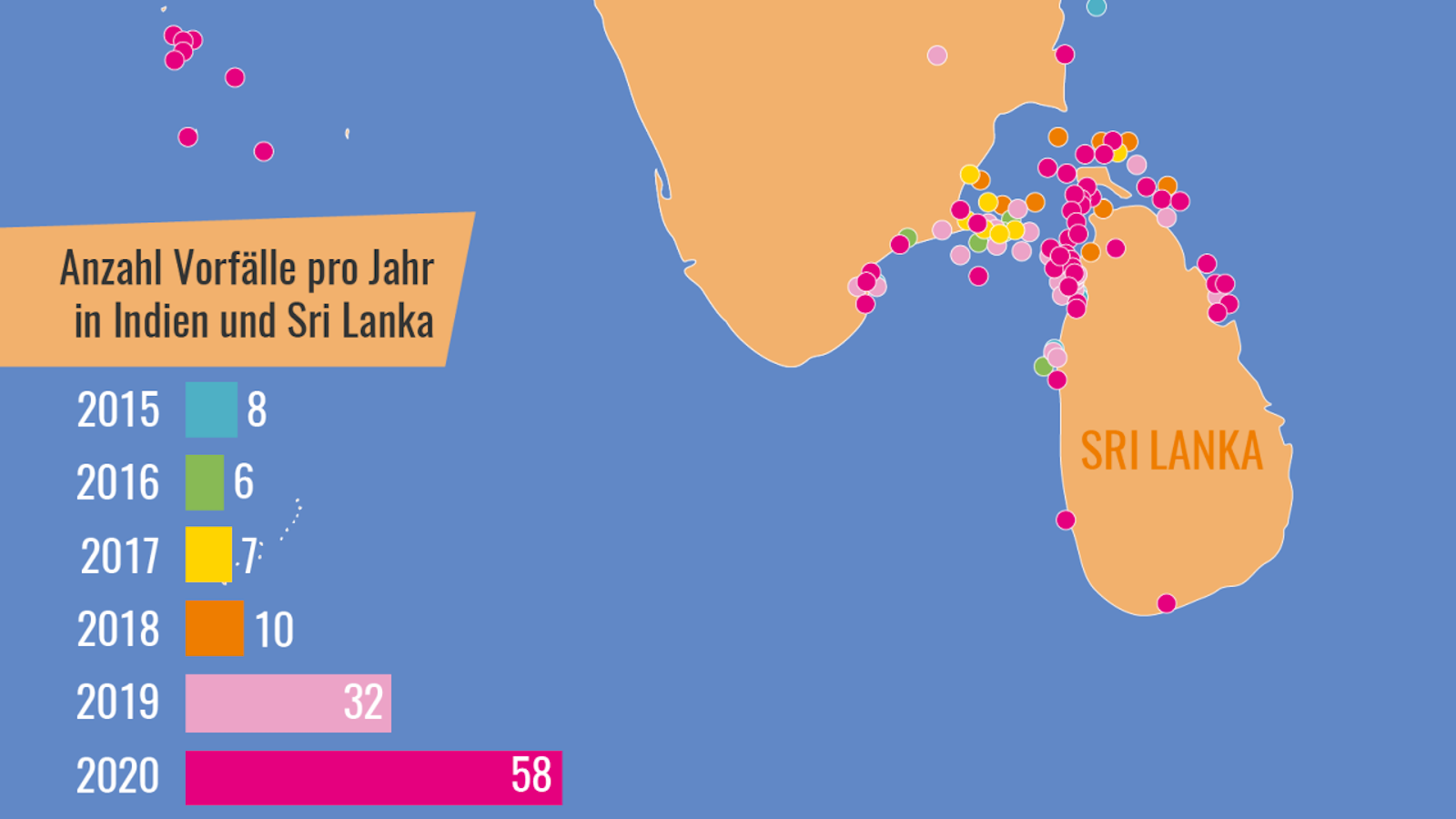

The fungus colonizes, kills, and feeds off the root systems of both coniferous and hardwood trees. Armillaria root disease occurs in forests worldwide, and in North America, it’s particularly prevalent in the Pacific Northwest of the U.S.

But why are the ones in Malheur National Forest so particularly vast and old? Scientists are unsure but, of course, have a few theories.

“Armillaria may have effectively spread in historic forests of large trees that were less-densely stocked, and composed of species less susceptible to root disease,” a Forest Service publication dedicated to the humongous fungus (mark two) speculates.

“Alternatively, forest structure and composition are now possibly more amenable to Armillaria spread as current conditions are different from those that developed under the natural fire regimes of the last several hundred years.”

Danger: dead trees

To hikers itching to go check out the world’s largest mushroom, two warnings. One: Watch where you go. As mentioned, the fungus kills trees, and dead trees standing around may fall over at any time. So don’t walk near, push against, or even stand close to any.

And two: You won’t see the giant shroom — only its effects. Fact-checkers at Snopes have debunked images of huge mushrooms sprouting overground, towering over visitors like fungal redwoods.

The bulk of those 60 Boeing 747s are hidden underground and inside the trees that the fungus is consuming. Only for a short time in the fall, usually following the first rains, do honey mushrooms appear at the base of trees infected or recently killed by the fungus.

Can those mushrooms and the network they emanate from really be counted as one and the same organism? That depends on the definition. Identical twins share the same genes but don’t count as a single organism (though some do a good imitation of one). The Humongous Fungus does fit a more prescribed definition: It’s a set of genetically identical cells that communicate, coordinate, and share a common purpose. (No brain needed!)

As slow and sneaky movers, earthbound and parasitic, fungi may strike us free-roaming mammals as a weird and not particularly enviable variety of life. But both humongous fungi and their ilk demonstrate that they occupy a successful niche, measured by their longevity and size.

In fact, it is quite likely that somewhere out there, there’s a fungus that’s even more humongous than the current title holder.

Strange Maps #1261

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on X and Facebook.