Ken Burns on what we get wrong about Leonardo da Vinci

- Centuries of romanticized accounts have generated many popular misconceptions about the life and work of Leonardo da Vinci.

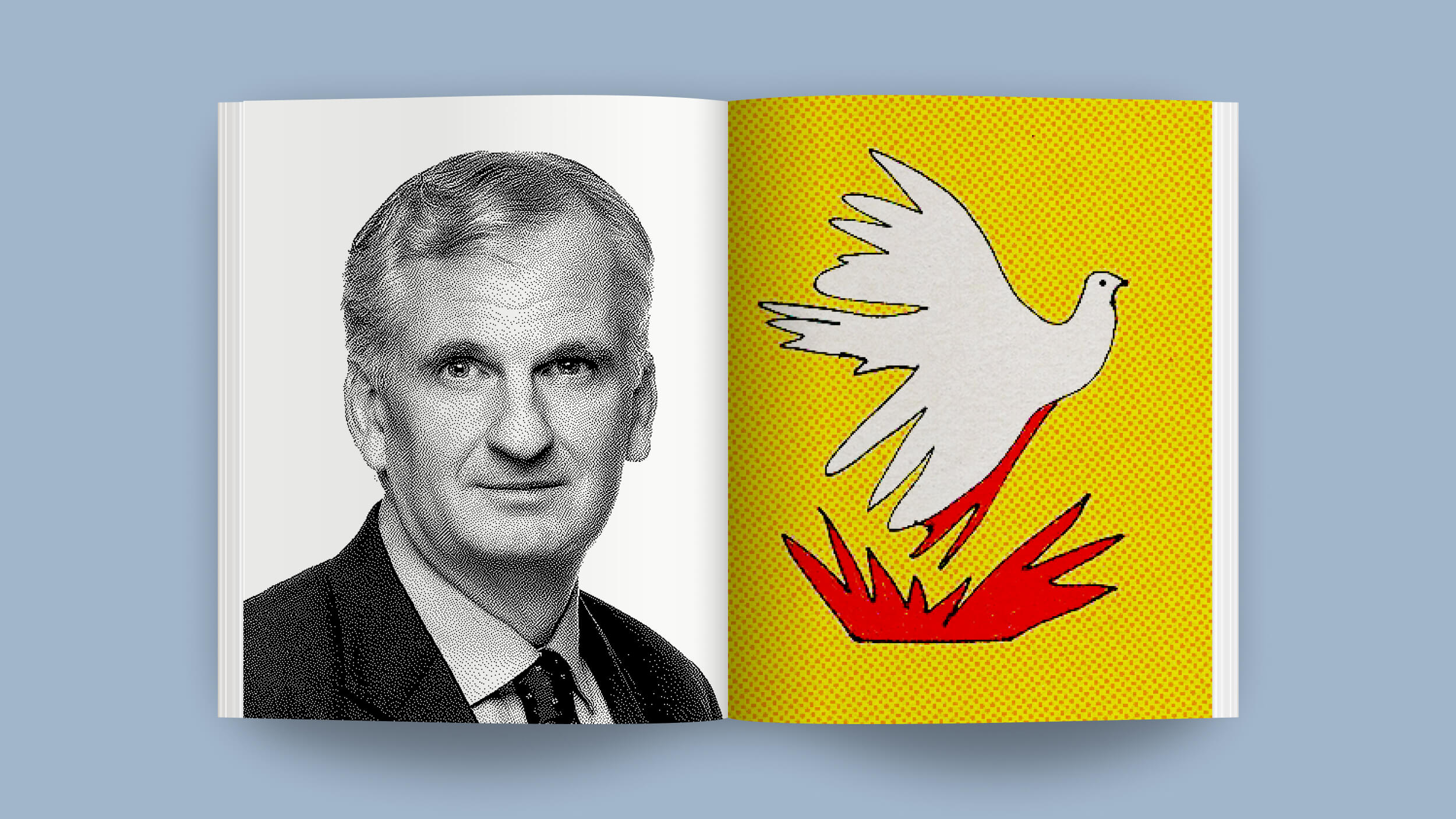

- A new documentary by filmmaker Ken Burns, known for his series on the Civil War, plans to dispel some of these myths.

- A polymath, da Vinci found most of his creative and scientific insights not in libraries, but outdoors, via direct observation of nature.

Despite his international renown, we know terribly little about Leonardo da Vinci. Aside from a couple of Florentine court records about a dropped sodomy accusation, and — of course — his own notebooks, his name survives primarily through his work, his idiosyncratic drawings, paintings, and blueprints.

Idiosyncratic, for while da Vinci apprenticed with established masters, like sculptor and painter Andrea del Verrocchio, and was, like many a Renaissance man, well-acquainted with the writings of Greek and Roman philosophers, most of his artistic and scientific insights came to him through direct observation of the natural world rather than craftsmanship or scholarship.

This, coincidentally, is one of the main messages hammered home in Leonardo da Vinci, a new documentary by Ken Burns. Set to air on PBS in November, it aims to clear up some common misconceptions about Da Vinci’s life and legacy that centuries of romanticization — from academically dubious biographies to Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code — have led us to confuse for fact.

The real da Vinci, Burns’ documentary argues, didn’t actually invent the modern-day tank or helicopter. Nor was he a religious mystic with ties to the secret origins of Christianity. He was, on the contrary, an extremely rational man whose boundless curiosity enabled him to draw conclusions others overlooked. Da Vinci also wasn’t a polymath — a jack-of-all-trades — so much as he was an interdisciplinarian, someone who saw the fields of art, mathematics, geology, physics, and chemistry not as separate but complementary, each contributing to a more complete understanding of reality.

In the following interview, Burns discusses not only what people often get wrong about da Vinci but also how his work, like that of his subject, is driven above all by genuine interest and wonder.

The real Leonardo

“Leonardo is incredibly modern despite living more than 500 years ago,” Burns tells Big Think when asked what drew him to this particular and arguably overdone subject. “Not because he invented the helicopter — he didn’t — but because he had an immense curiosity. He remains relevant today because of his ability to question and explore.”

Perhaps the biggest misconception about da Vinci is that he was a man of his time, a product of the Renaissance and its renewed interest in the art and science produced during classical, pre-Christian antiquity. In truth, some of his biggest breakthroughs resulted from him ignoring the erroneous beliefs of his contemporaries and going back to the source, to nature.

“His circumstances, including being born out of wedlock and therefore unable to attend university,” notes Burns, “meant his greatest teacher was nature. He was constantly making connections, seeing how the veins in a leaf mirrored those in a hand, for example. He did not readily accept the knowledge that came before him; he questioned it, dissected it — literally.”

Da Vinci didn’t merely cut open the bodies of people and animals but also made wax models of their organs to recreate the hydraulic properties of blood flow using water and seeds. “It took centuries for modern imaging technology to prove that he was right,” notes Burns. “And this is a man who didn’t have access to a microscope or telescope.”

His scientific research also informed his art, which — creative liberties aside — he treated as an accurate, organized reproduction of nature’s outward appearance: light striking objects, objects casting shadows, muscles and bones showing underneath the skin, and how everything we see is warped by perspective.

One of his first completed paintings, The Annunciation (1472-1476), in which the Archangel Gabriel informs Mary that she is pregnant with the son of God, combines his various interests, including anatomy, drapery, plant life, and architecture, into a single, unprecedently complex image. Many of his beloved portraits, including the Mona Lisa, were painted in sfumato, a technique in which gradations in color, tone, and value are kept subtle to the point of imperceptibility. Da Vinci took this technique further than any of his peers, applying as many as 40 layers of thin and almost transparent oil paint to make the skin of his subjects appear translucent and lifelike.

He seldom finished paintings and, on one occasion, applied to work for the Duke of Sforza as a military engineer to escape the creative and intellectual limitations that came with regular commissions — all signs that he wasn’t driven by money or fame but rather a genuine desire to understand how the world worked. To this end, the PBS documentary points out that, while da Vinci wasn’t particularly religious in the conventional, Catholic sense of the word, he did perceive his surroundings to be part of an overarching system — a system which, like God, he judged perfect and unimprovable.

Beyond documentary

If you live in the U.S., chances are you know Burns first and foremost from The Civil War, his hugely popular 1990 miniseries that turned the eponymous conflict from the stuff of scholars and obsessive grandfathers into a widely known, widely discussed subject — and that’s no small feat. Today, most documentaries are glorified Wikipedia articles with talking heads, only mildly more interesting to the average viewer than the books they’re based on. At best, though, they capture the cultural Zeitgeist by making important scholarship available and appealing to the masses.

One way that Burns elevates his documentaries above those aforementioned Wikipedia adaptations is by letting his subjects dictate the form of the documentary itself, thus ensuring no two films feel the same. “Leonardo remains an enigma in many ways, especially regarding the specifics of his personal life,” he says. “Despite the thousands of pages of notes and drawings he left behind, we know very little about the details of his day-to-day life. That actually gave us some creative freedom. We didn’t feel obligated to speculate much about his personal life, which allowed us to focus on his work and ideas.”

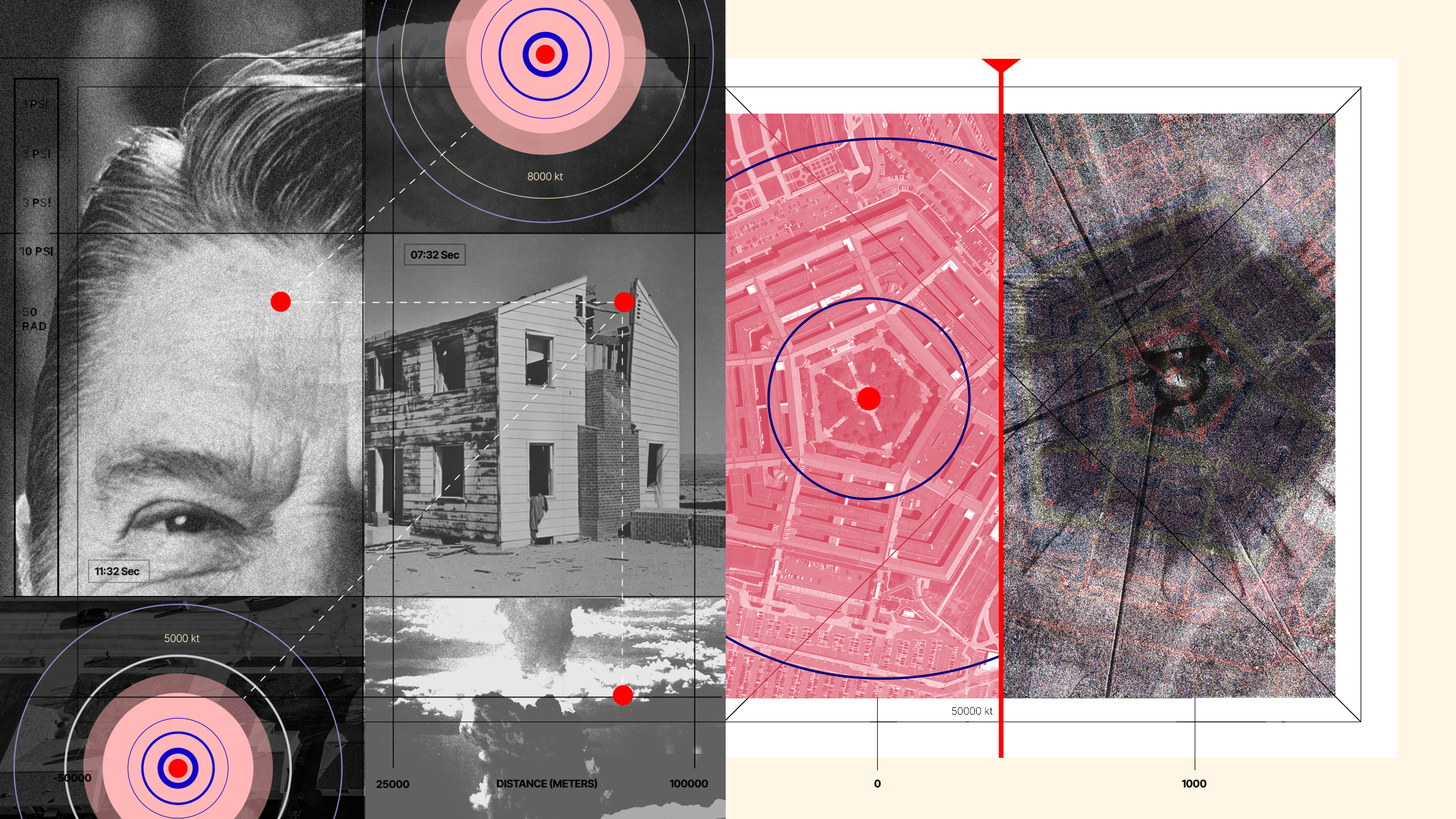

Inspired by da Vinci’s interdisciplinary approach, Leonardo da Vinci features a lot of split screens, showing blueprints for his devices alongside images of plants and animals that inspired them, or of modern-day machinery that heavily resembles his initial designs. The film also includes a wide variety of interview subjects, speaking not only to da Vinci’s varied interests but also to the range of people and professions who turn to him for inspiration. Aside from your regular ensemble of writers and historians, you’ll also hear from some contemporary artists, as well as filmmaker Guillermo Del Toro.

“I wholeheartedly subscribe to the latter,” Burns says when asked if he thinks a good documentary is supposed to package history — make it presentable and palatable, the way many world-class museums now feature interactive exhibitions — or let it speak for itself, unaffected by the taste or knowledge level of its audience. Helping history speak for itself might be a better way to put it, as the past is, after all, dead, and has to be resurrected by the living in order to be passed down. Whether he’s making a documentary about da Vinci or Abraham Lincoln, the heart of Burns’ job is therefore mainly about figuring out how to bring history to life without distorting it:

“Documentary filmmaking has had a long and honorable tradition of advocating for certain social or political causes. And some of my favorite documentaries fall into that category. But by choosing to focus on history, I felt it was important to surrender to the facts and remain as impartial as possible—just like umpires calling balls and strikes in a baseball game. The past is already incredibly dramatic, and if you leave it alone, it becomes even more so.”

Like da Vinci, Burns’ admiration of history — of the overarching system of human civilization — borders on the religious. “God is the greatest dramatist,” Shelby Foote, a writer and historian featured in Civil War, once told him. Put differently — and less literally — there is no story more fascinating, surprising, and moving than the complete, collective story of our species, with all its contradictions and complications left intact.

“The key is to tell the story as it happened,” Burns reiterates. “There’s no need to take liberties. People can still draw their own conclusions from the complexities and contradictions that naturally arise. Even the greatest heroes have their flaws, and even the worst villains have some humanity. If you’re honest about those complexities, the story speaks for itself. Of course, the selection of which facts to include already introduces some subjectivity – nothing is truly objective – but you can still honor the complexities.”

As composer Wynton Marsalis said in Burns’ 2001 film Jazz, about the history of the genre, “a thing and the opposite of a thing [can be] true at the same time.”

“If you can hold that duality,” Burns affirms, “you’re not trapped in a binary where you’re forced to make a specific political point. When we made our Vietnam documentary in 2007, for example, we expected a huge controversy and had a team ready to respond to attacks from both sides of the political spectrum. But in the end, we received almost no criticism because the story was so compelling that it spoke for itself.”

“At the end of the day,” he concludes, “it’s about constructing a story that honors the contradictions of real life, where someone can be both one thing and its opposite. That’s not a secret – it’s just the key to good storytelling.” Coincidentally, it’s also the key to understanding Leonardo da Vinci.