Richard Dawkins on reverse engineering evolution’s optimal beauty

- Engineers use “reverse engineering” to discern the purpose of a machine, even if that purpose had originally been lost to time.

- Richard Dawkins shows how an analogous process can be used to understand the purpose of evolved characteristics in living creatures.

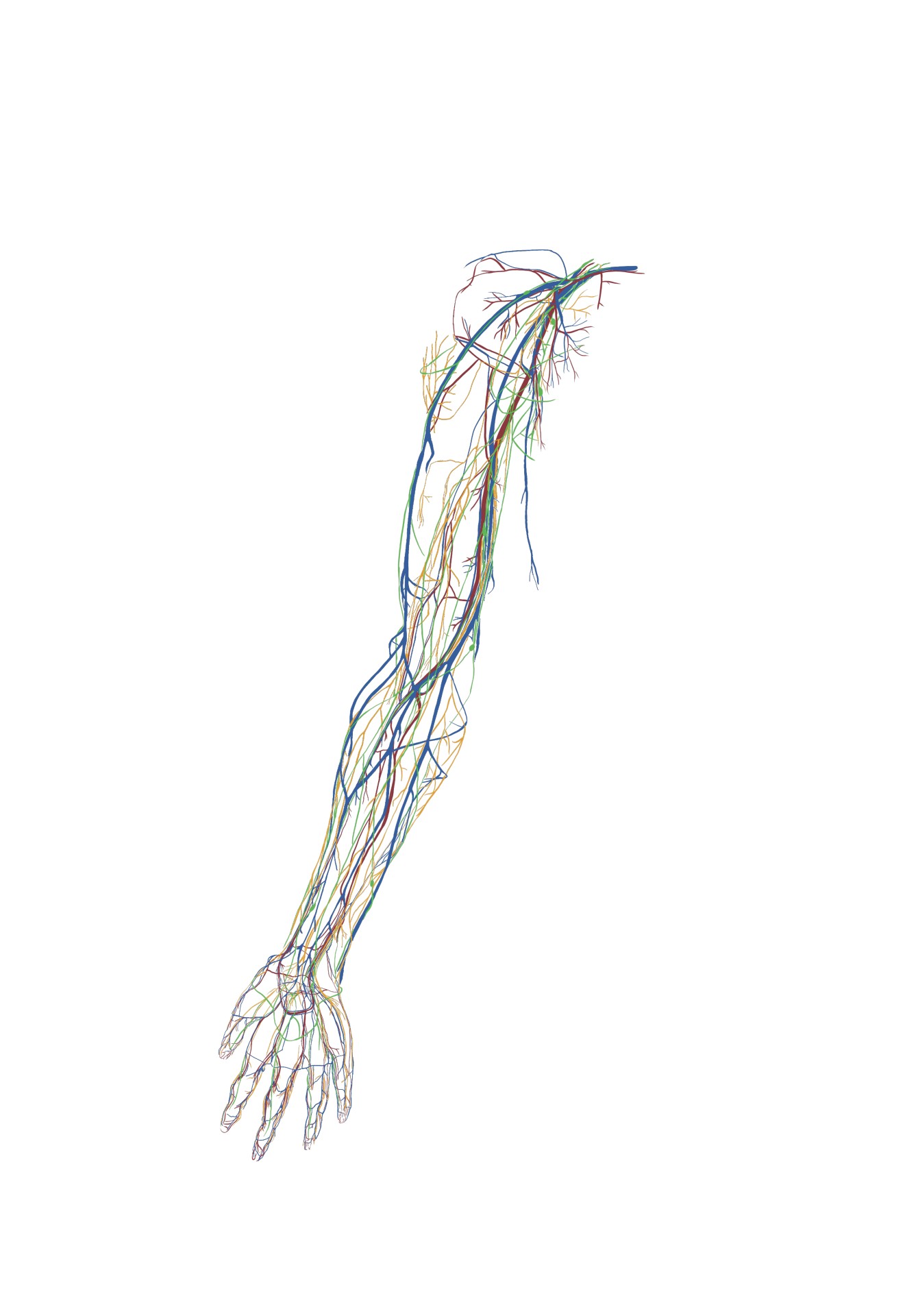

- Even internal anatomy — bewilderingly messy and complex — will ultimately reveal its beautiful elegance to the trained eye.

Engineers assume that a mechanism designed by somebody for a purpose will betray that purpose by its nature. We can then “reverse engineer” it to discern the purpose that the designer had in mind.

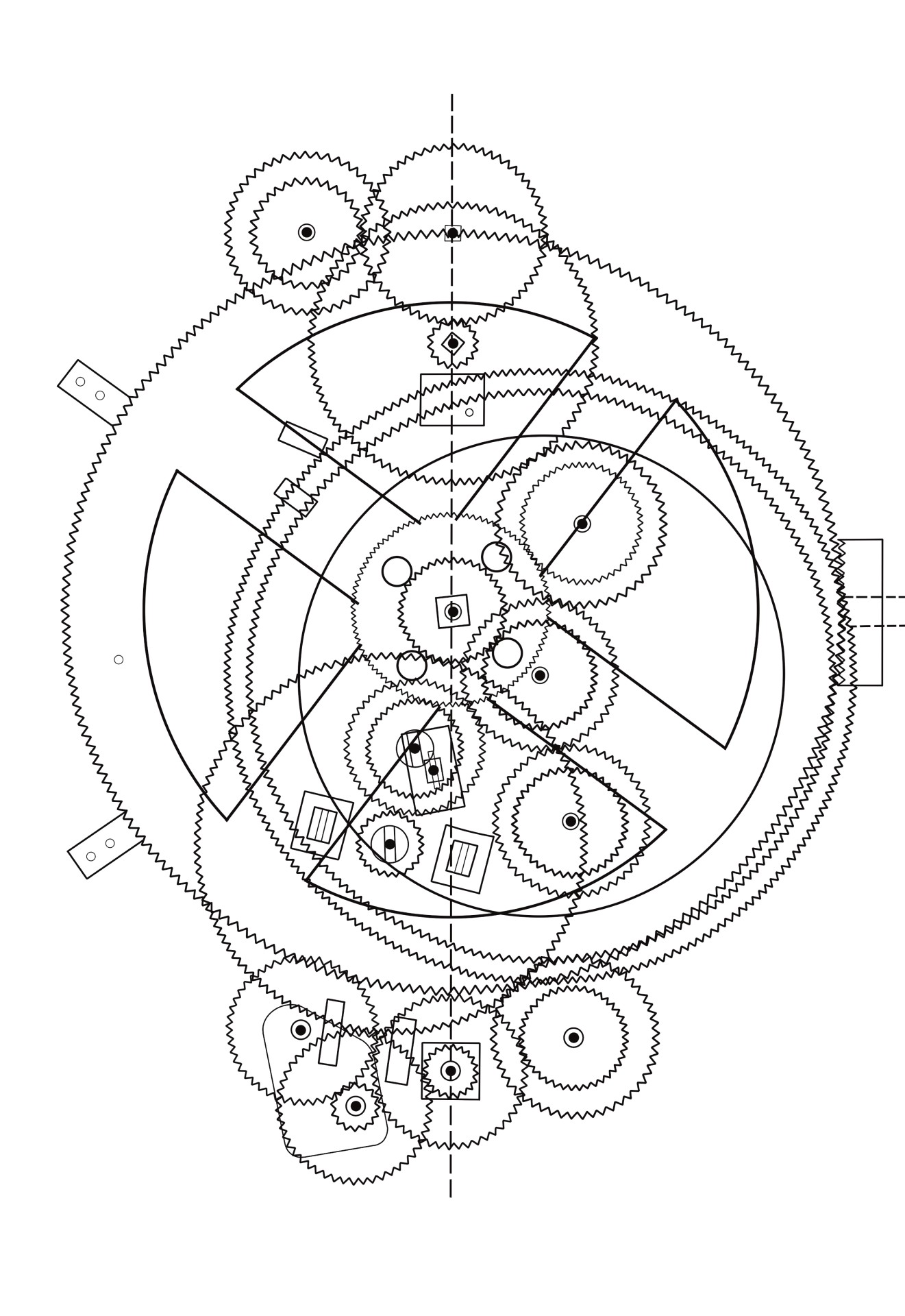

Reverse engineering is the method by which scientific archaeologists reconstructed the purpose of the Antikythera mechanism, a mesh of cogwheels found in a sunken Greek ship dating from about 80 B.C. The intricate gearing was exposed by modern techniques such as X-ray tomography. Its original purpose has been reverse engineered as an ancient equivalent of an analogue computer, designed to simulate the movement of heavenly bodies according to the system of epicycles later associated with Ptolemy.

Reverse engineering assumes that the object facing us had a purpose in the mind of a competent designer, a purpose that can be guessed. The reverse engineer sets up a hypothesis as to what a sensible designer might have had in mind, then checks the mechanism to see if it fits the hypothesis. Reverse engineering works well for animal bodies as well as for man-made machines. The fact that the latter were deliberately designed by conscious engineers while the former were designed by unconscious natural selection makes surprisingly little difference: a potential for confusion readily exploited by creationists with their characteristically eager appetite for it. The grace of a tiger and of its prey could not easily, it would seem, be bettered:

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame thy fearful symmetry.

Darwin had a section of Origin of Species called “Organs of extreme perfection and complication.” It’s my belief that such organs are the end products of evolutionary arms races. The term “armament race” was introduced to the evolution literature by the zoologist Hugh Cott in his book on animal coloration published in 1940, during the Second World War. As a former officer in the regular army during the First World War, he was well placed to notice the analogy with evolutionary arms races. In 1979, John Krebs and I revived the idea of the evolutionary arms race in a presentation to the Royal Society. Whereas an individual predator and its prey run a race in real time, arm races are run in evolutionary time, between lineages of organisms. Each improvement on one side calls forth a counter-improvement on the other. And so the arms race escalates, until called to a halt, perhaps by overwhelming economic costs, just like military arms races.

Antelopes could always outrun lions, and vice versa, but only by counter-productive investment of too much “capital” in leg muscles at the expense of other calls on investment in, say, milk production. If the language of “investment” sounds too anthropomorphic, let me translate. Individuals who excel in running speed would be out-competed by slightly slower individuals who divert resources more usefully, from athletic legs into milk. Conversely, individuals who overdo milk production are out-competed by rivals who economize on milk production and put the energy saved into running speed. To quote the economists’ hackneyed saw, there’s no such thing as a free lunch. Trade-offs are ubiquitous in evolution.

I think arms races are responsible for every biological design impressive enough to, in the words of David Hume’s [fictionalized philosopher] Cleanthes, ravish “into admiration all men who have ever contemplated them.” Adaptations to ice ages or droughts, adaptations to climate change, are relatively simple, less prone to ravish into admiration because climate is not out to get you. Predators are. So are prey, in the indirect sense that, the more success prey achieve at evading capture, the closer their would-be predators come to starvation. Climate doesn’t menacingly change in response to biological evolution. Predators and prey do. So do parasites and hosts. It is the mutual escalation of arms races that drives evolution to Cleanthean heights, such as the feats of mimetic camouflage or the sinister wiles of Cuckoos.

And now for a point that at first sight seems negative. Whereas animals look beautifully designed on the outside, as soon as we cut them open, we seem superficially to get a different impression. An untutored spectator of a mammal dissection might fancy it a mess. Intestines, blood vessels, mesenteries, nerves seem to spill out all over the place. An apparent contrast with the sinewy elegance of, say, a leopard or antelope when seen from outside. [But] the perfection typical of the outer layer must pervade every internal detail as well. Now compare your heart with the village pump, which seems neatly and simply fit for purpose. Admittedly, the heart is two pumps in one, serving the lungs on the one hand and the rest of the body on the other. But you could be forgiven for wondering whether a more minimally elegant pump might profitably have been designed.

The backwards wiring of the vertebrate retina is well compensated by post-hoc making good. You might think that “from such warped beginnings nothing debonair can come.” The great German scientist Hermann von Helmholtz is said to have remarked that if an engineer had produced the eye for him, he would have sent it back. Yet after tweaking, “in post” as movie-makers say, the vertebrate eye can become a fine piece of optical kit.

Why do animals look obviously well designed on the visible outside but apparently less so inside? Does the clue reside in that word visible? In the case of camouflage, and also ornamental extravaganzas like the peacock’s fan, (human) eyes are admiring the external appearance of the animal, and (peahen or predator) eyes are doing the natural selection of external appearance: similar vertebrate eyes in both cases. No wonder external appearance looks more perfectly “designed” than internal details. Internal details are every bit as subject to natural selection, but they don’t obviously look that way because it is not selection by eyes.

That explanation won’t do for the streamlined flair of a sprinting cheetah or its equally graceful Tommy prey. Those beauties did not evolve for the delectation of eyes but to satisfy the lifesaving requirements of speed. Here it would seem to be the laws of physics that impose what we perceive as elegance: as it is for the aerodynamic grace of a fast jet plane. Aesthetics and functionality converge on the same stylish elegance.

I confess that I find the interior of the body bewilderingly complex. I might even go so heretically far as to dismiss it as a mess. But I am a naive amateur where internal anatomy is concerned. A consultant surgeon whom I have consulted (what else should one do with a consultant?) assures me in no uncertain terms that, to his trained eye, internal anatomy has a beautiful elegance, everything neatly stowed away in its proper place, all shipshape and Bristol fashion. And I suspect that “trained eye” is exactly the point. My eye sees elegance on the outside. Then when I cut an animal open, my amateur eye contemplates only a mess. The trained surgeon sees stylish perfection of design, inside as well as out. Yet there is more to be said. Something about embryology.

The skeptic vocally doubts whether it can really matter whether this vein in the arm passes over or under that nerve. Maybe it doesn’t in the sense that, if their relationship could be reversed with a magic wand, the person’s life might not suffer, and might even improve. But I think it does matter in another sense. Every nerve, blood vessel, ligament, and bone got that way because of processes of embryology during the development of the individual. Exactly which passes over or under what may or may not make a difference to their efficient working, once their final routing is achieved. But the embryological upheaval necessary to effect a change, I conjecture, would raise problems, or costs, sufficient to outweigh other considerations. Especially if the embryological upheaval strikes early. The intricate origami of embryonic tissue-folding and invagination follows a strict sequence, each stage triggering its successor. Who can say what catastrophic downstream consequences might flow from a change in the sequence — the kind of change necessary to re-route a blood vessel, say.

Moreover, perhaps Darwinian forces have worked on human perception to sharpen our appreciation of external appearances as opposed to internal details. It is entirely unreasonable to suppose that the chisels of natural selection, so delicately adept at perfecting external and visible appearance, should suddenly stop at the animal’s skin rather than working their artistry inside. The same standards of perfection must pervade the interior of living bodies, even if less obviously to our eyes. To dissect the non-obvious and make it plain will be the business of future zoological reverse engineers, and it is to them that I appeal.