How Hitler Turned Interior Design into Propaganda

With a single shot in September 1931, Adolf Hitler’s rise to power almost ended before it even began. Geli Raubal, Hitler’s young half-niece, took her life with Hitler’s gun in his Munich apartment, just as the former rabble-rouser was looking to claim control through legitimate, electoral means. The old political adage about dead girls and live boys threatened to tarnish Hitler in the public eye. The Nazis waged a massive public relations campaign in response, transforming every aspect of Hitler’s life, including where he lived. Despina Stratigakos’ Hitler at Home examines the often overlooked aspects of Hitler’s homes in that propaganda, which produced a “home front” façade that fooled not only the German people, but also people overseas.

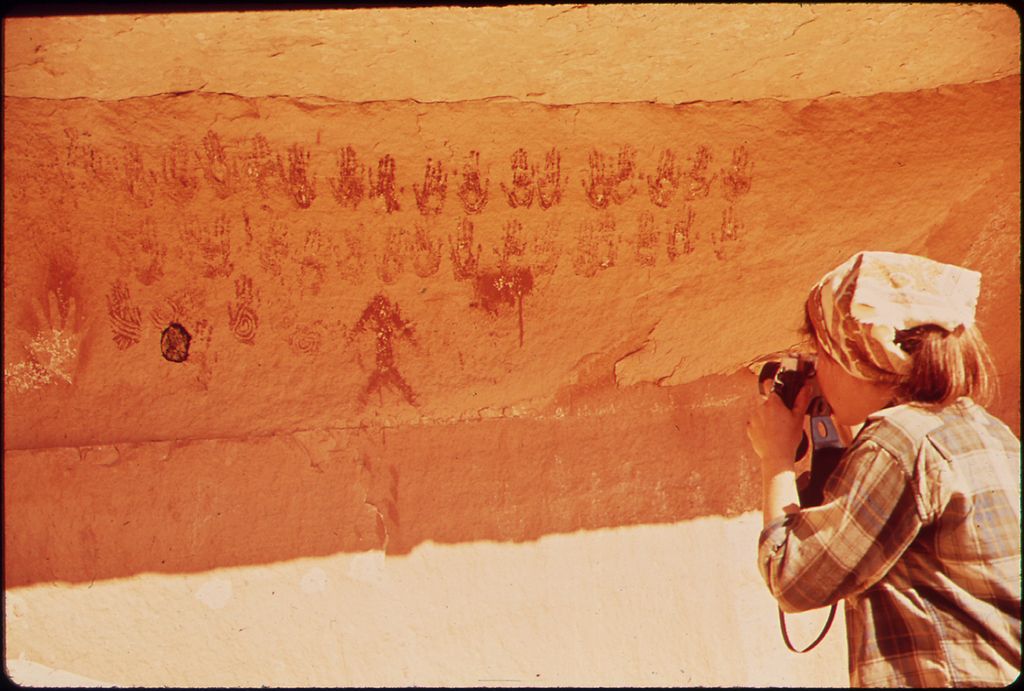

Image: Adolf Hitler, Gerdy Troost, Adolf Ziegler, and Joseph Goebbels on a tour of the Haus der Deutschen Kunst, May 5, 1937. Image source: “Bundesarchiv Bild 183-1992-0410-546, München, Besichtigung Haus der Deutschen Kunst” by Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1992-0410-546 / CC-BY-SA 3.0. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 de via Wikipedia Commons.

Stratigakos, a historian and writer, seems the perfect guide to Hitler’s “home cooked” image. She specializes in how architecture portrays power, with a particular interest in German architecture and power and the role (or lack of) of women, as shown in her 2008 book A Women’s Berlin: Building the Modern City and the forthcoming Where Are the Women Architects? Scholars have long discussed the Nazi fascination with art and architecture, commenting usually on Albert Speer, but Stratigakos focuses on Hitler’s other favorite architect and interior designer, Gerdy Troost (shown beside Hitler above), and on how Troost worked in smaller, subtler ways to build the Hitler myth beside the bigger, more obvious designs of Speer and others.

The post-scandal Hitler needed to erase all the bad connotations of his niece’s suicide and their unusual (romantic?) living arrangements. Nazi propagandists quickly floated puff pieces about their leader as a hard-working, cultured, self-sacrificing bachelor married to his work of making Germany great again. In these Better Homes and Gardens-esque features, Hitler’s homes were continually featured as an exterior manifestation of the personal Hitler nobody knew. Stratigakos avoids a “biography told through architecture” (as that propaganda did) to deconstruct that “domestic” Hitler manufactured for public consumption.

Image: The “Great Hall” of the Berghof. Image source: “Bundesarchiv Bild 146-1991-077-31, Obersalzberg, Berghof, Große Halle” by Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1991-077-31 / CC-BY-SA 3.0. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 de via Wikipedia Commons.

Once Hitler — satisfactorily “sold” to the German public — rose to power through a serious of political compromises, he began rebuilding the German public “house” of the Old Chancellery as well as his own private house, the Berghof, which means in German “farmer’s house” or “farmer’s court,” an appropriate combination of rustic roots and power associations for Hitler’s volk-based aspirations. Hitler hired architect Paul Troost to reimagine the Old Chancellery in his neoclassical style. When Paul died in 1934, his wife Gerdy and his assistants (as Atelier Troost) finished the projects and continued to work for Hitler until the Reich’s end to create the distinctive “look” of Hitler’s power. “Within a syntax of spare classicism,” Stratigakos writes, “the Atelier Troost employed a vocabulary of specific forms, colors, and materials that produced a distinctive visual language of power. Whether private or public, the Atelier Troost interiors were immediately recognizable as the Fuhrer’s spaces.” Just one look at the Berghof’s “Great Hall” (shown above) and you knew you were in the presence of naked power.

Image: Adolf Hitler greets British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain on the steps of the Berghof. Image source: “Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H12478, Obersalzberg, Münchener Abkommen, Vorbereitung” by Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H12478 / CC-BY-SA 3.0. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 de via Wikipedia Commons.

Hitler used Troost’s designs to maximum effect in his political dealings. When British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain visited Hitler to negotiate the infamous Munich Agreement he’s become synonymous for, he first encountered the grandeur of the Berghof (shown above). Later, in the quieter, book-lined, art-filled rooms of the Berghof, Chamberlain encountered the “civil, cultured” Hitler who you could trust to keep a promise as a man of culture and taste. Stratigakos shows how Troost’s interior design and Hitler’s ulterior motives worked hand in glove to deceive not only diplomats like Chamberlain, but also an international public (including isolationist Americans) into thinking that Hitler was a man of peace who would never pursue war.

Today, it’s hard to imagine that anyone would fall for such a deception. Paintings such as Paris Bordone’s Venus and Amor lined the Berghof’s “Great Hall” as almost cartoonish symbols of Hitler’s hypermanliness and heterosexuality to counter allegations of homosexuality against the notorious bachelor. (Eva Braun’s existence was a well-kept secret until the end of the war.) After hostilities began, contemporaries spoofed Hitler’s private image in cartoons and the Allies bombed the Berghof at the end of the war as Hitler cowered in his Berlin bunker, but the myth of Hitler’s power and cultured persona lived on.

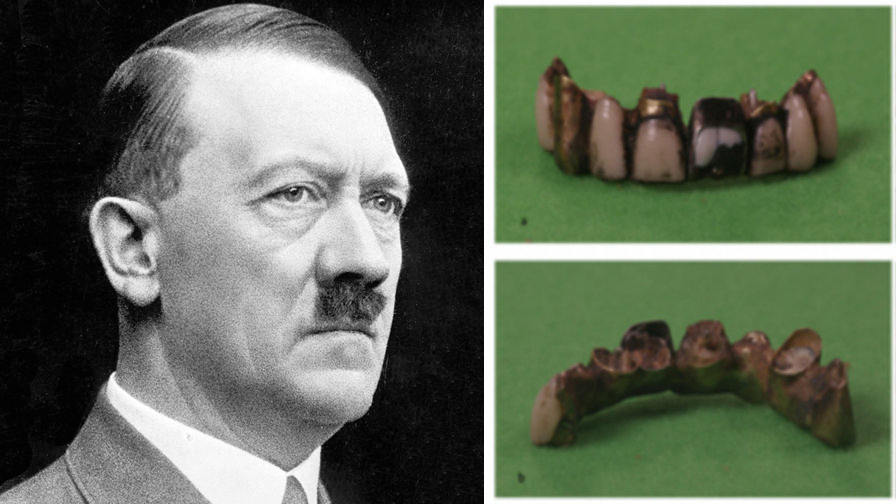

When photographer Lee Miller entered Hitler’s Munich apartment — where that niece died years before — with the dust of Dachau’s dead stuck to her boots, Miller posed bathing in Hitler’s bathtub as the ultimate image of Hannah Arendt’s phrase, “the banality of evil.” This wasn’t some kind of superbeing, Miller tried to show, just another guy who liked free shampoo samples (true!). The final takeaway from Despina Stratigakos’ Hitler at Home isn’t really about Hitler as much as about the pernicious persistence of propaganda to deceive. The idea of Hitler as a cultured, dog-loving being rather than a monster of epic proportions (who tested his cyanide suicide pills on his dogs) continues to thrive in too many minds, and too many young minds thanks to a lack of historical education. “More than 75 years later,” Stratigakos concludes sadly, “the distorting mirror of Hitler at home continues to deceive.” Hitler at Home should make all Hitler apologists, of any degree, look in the mirror a little closer.

[Image at Top of Post: Adolf Hitler in 1942 at the Berghof with his long-time lover, Eva Braun, whom he married on April 29, 1945. Image source: Bundesarchiv B 145 Bild-F051673-0059, “Adolf Hitler und Eva Braun auf dem Berghof” by Bundesarchiv, B 145 Bild-F051673-0059 / CC-BY-SA. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 de via Wikipedia Commons.]

[Many thanks to Yale University Press for providing me with a review copy of Despina Stratigakos’ Hitler at Home.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]