Why Politicians All Seem The Same, Gas Stations Come In Pairs and Twitter is Turning Into Facebook

Twitter was alive with the sound of mild bemusement yesterday, as the social network took another step toward emulating Facebook by replacing its “favourite” button with a “like” button. The change follows more controversial moves by Twitter to imitate Facebook, such as the adoption of algorithms to promote popular posts rather than sticking solely to its original philosophy of providing an unmolested “firehose” of information.

Over the last 24 hours, much has been written about Twitter’s professed reasoning for the latest change — but is it really the case that as Twitter claims, people didn’t understand the point of the favourite button? One alternative theory suggested by J.P. de Ruiter, a cognitive scientist and psycholinguist at Bielefeld University in Germany is that the decision can be explained by Game Theory.

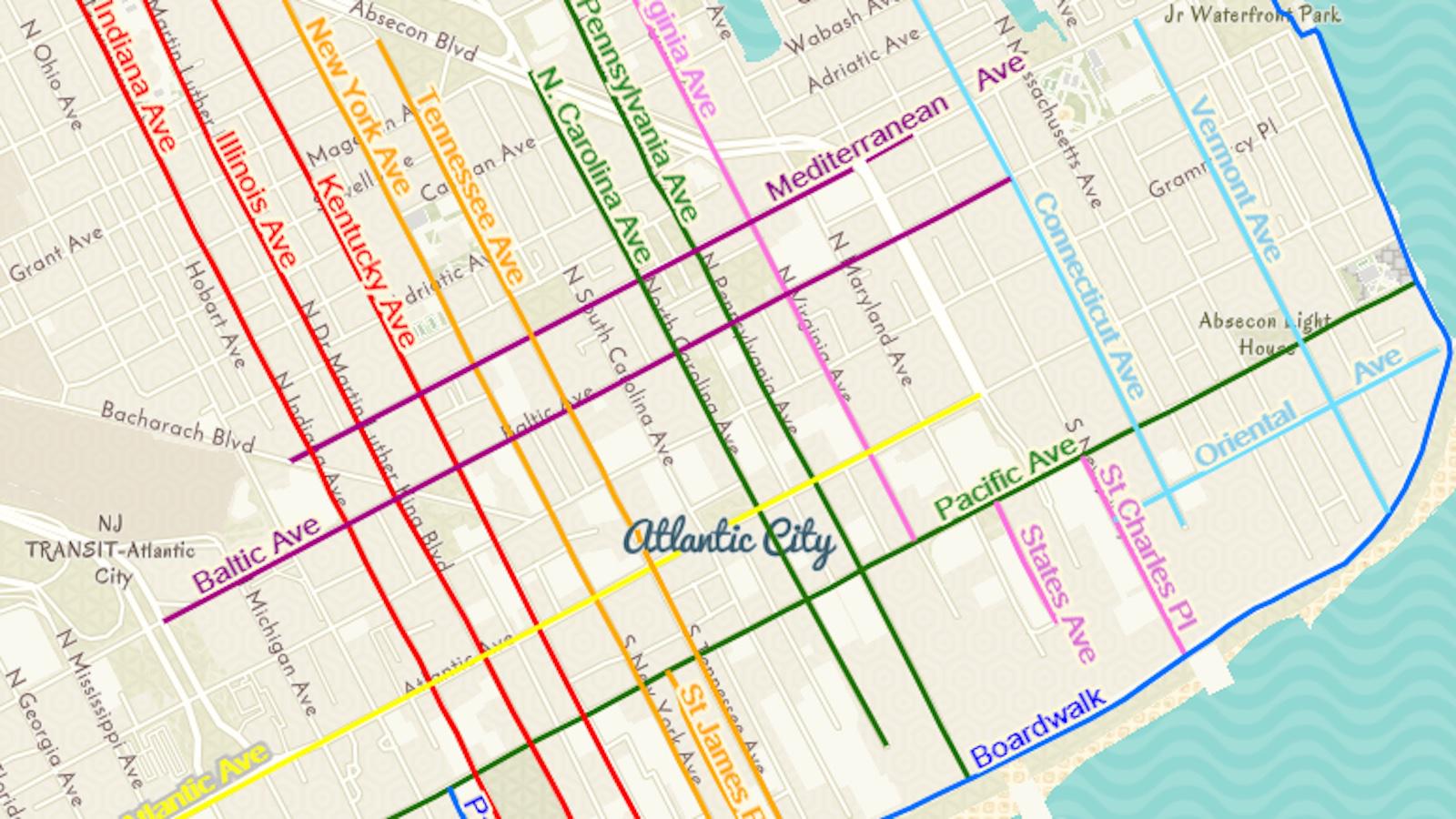

As soon as there are two shops on the same street, according to Hotelling’s law, the second shop will end up located directly beside the first shop.

De Ruiter explains: “I heard rumours that Twitter is going to extend their character limit. Now I see that they copied the positive feedback mechanism from Facebook. Given that they (Twitter) are not satisfied with their growth, and that Facebook is a direct competitor, I thought of Hotelling’s law, where for game-theoretical reasons, companies do not diversify but rather tend to occupy the same customer space. This may well be Twitter’s real intention, instead of their claimed aim of increasing accessibility.”

Hotelling’s law is a phenomenon from the field of economics that explains why you so often see groups of pharmacies, groups of betting shops, and groups of grocery stores right next to each other, when common sense would suggest that the community would be far better served if stores of the same kind were not grouped together. The same phenomenon is also true of politics; one doesn’t need to look far to hear the familiar cry that “X” party that is supposed to be in opposition to “Y” party is “mimicking their opponents” or making a “rush for the centre ground.”

So why is it that setting up a store next door to a competitor isn’t diabolically bad for business? Take the analogy given in Hotelling’s Law of a single street with customers dotted evenly down the length of the road. Each store owner (read: social network owner or politician) has the goal of locating their “shop” where it will receive the most customers. Each customer, all other things being equal, will visit the nearest shop. If there is a monopoly, it doesn’t matter to the store owner where they place their shop, but as soon as there are two shops on the same street, according to Hotelling’s law, the second shop will end up located directly beside the first shop. This is because if the second shop places itself at any other point along the line, one or other of the two shops will have a competitive advantage. When this happens, this leads the other shop to attempt to regain the upper hand by moving closer to the competing shop; the process continues until both shops end up next door to each other resulting in a Nash equilibrium.

For a visual demonstration of Hotelling’s law playing out in practice, check out the explanation below from Phil Smith:

—

Formerly writing with the pseudonym “neurobonkers”, Simon has a history of debunking dodgy scientific research and tearing apart questionable science journalism in an irreverent style. Simon has written and blogged for publishers including: The Psychologist, Nature, Scientific American and The Guardian. His work has been praised in the New York Times and The Guardian and described in Pearson’s Textbook of Psychology as “excoriating reviews of bad science/studies”.

Follow Simon Oxenham on Twitter, Facebook, Google+, RSS, or join the mailing list to get each week’s post straight to your inbox. Image Credit: Shutterstock/Sean Pavone