Our Alien World: a Burmese Spirit Map

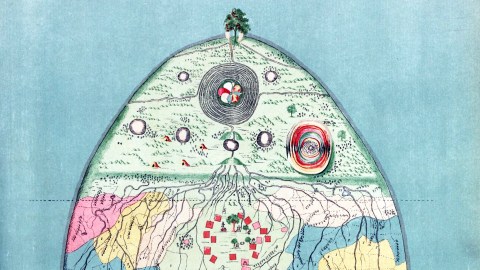

The oceans on this Burmese map of the world are as flat and blue as ours. That much is familiar at least. But the land masses rising from their waves are unlike anything in Western cartography.

They have no bearing on the shape and position of the actual continents, mapped with increasing precision as the Age of Discovery progressed. Nor do they resemble the sacred geography of the Jerusalem-centred T-O maps that preceded them.

This looks like a wholly alien world and, for lack of legend or context, an almost entirely unknowable one. So what is Planet Burma actually like? To describe is to discover.

Once, it seems, the dry part of this world consisted of a single, teardrop-shaped continent. Something caused that teardrop to shatter. Now the southern half is scattered in myriad islands of various sizes, all but the smallest of which are also tear-shaped.

The outline of the old one-piece continent is still visible. Outside the dotted line, the southern islands are all pink. Inside it, mostly yellow (in the east) or green (in the west). A few ships are seen sailing between them.

Perhaps the islands are colour-coded for the countries that hold them in possession, because those colours, plus white and a darker shade of green, quilt the southern portion of the main continent.

As on the islands, easily recognised topographic symbols denote mountains, lakes, and rivers. But the mainland is also crisscrossed by dotted lines, delimiting the coloured patches and smaller subdivisions within them. It’s perhaps not such a stretch to imagine that these lines refer to kingdoms and their provinces. And that those things that look like the male symbol (♂) but pointing straight up could refer to cities or towns.

The biggest kingdom on the map is the light green one, which dominates the centre and north of the continent (as well as those islands in the west). In the centre, a group of red squares surrounds a bunch of Buddha-like figures, a wooden shack, and a snake playing a mandolin — clearly symbolic of the empire’s capital city, brimming with opportunities for entertainment and enlightenment.

Toward the north, all the rivers feeding the various kingdoms of the world converge, somewhere in the wild lands that are dotted with hermit retreats (west), a psychedelic version of Stonehenge (east) and a continent-spanning string of circular lakes.

The World River is actually only one of four emerging from a maze-like whirlpool, centred on a giant lotus flower feeding the rivers, each of which flows toward one of the four cardinal directions. The rivers flowing east and west drain uneventfully into the ocean, but the northern river passes by what must be the tallest tree in the world, carrying some sort of red fruit.

Where is that tree? Or what does it mean? We are left completely clueless, for the only information the map comes with is the rather succinct legend: A Burmese Map of the World, showing traces of Mediaeval European Map-making. This is a page from a book titled The Thirty-Seven Nats — A Phase of Spirit-Worship prevailing in Burma, by Sir Richard Carnac Temple, published in London in 1906 by W. Griggs, “chromo-lithographer to the King.”

Sir Richard’s book is on full display in the digital collections of the New York Public Library. It shows the 37 great nats of Burmese folklore in gorgeous colour, two by two (except, of course, the last one).

Buddhism is the main religion in Burma (Myanmar), but the Burmese also worship spirits of a more local provenance. These are divided in 37 great nats, all human beings who met a violent death, and countless smaller nats, who are associated with trees, water, mountains, and other specific elements of nature.

Another iteration of the 37 nats, this time in black-and-white, is shown at the end of the book. Was this perhaps an Edwardian colouring book? In the middle of the book are a few related illustrations: a (Western) map of Burma, an overview of the sentient beings and their habitations according to Burmese Buddhist cosmogony, this map of the world and a Burmese map of hell — all without further comment.

A Burmese vision of hell.

Further research has not provided any more detail on what exactly this map shows, who made it, or why. The only scrap of extra information pertains to the when: The map supposedly was made in “about the 17th century.” It feels strange not to know more. But the lack of context is also liberating.

Go sit in that anthill-shaped hermit retreat and contemplate on the big questions of the world: Why is there something rather than nothing? Why does everything come in only seven colours? And how far away is that huge tree up north?

Sir R.C. Temple’s entire book found here at the New York Public Library’s Digital Collections. Copy of the world map (and that reference to the 17th century) here in the David Rumsey Map Collection.

Strange Maps #751

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].