Poor and happy: The societies that defy life satisfaction trends

- In a recent study, researchers surveyed 3,000 people living in poor, small-scale societies about their life satisfaction.

- The results found that these people’s life satisfaction is on par with people who live in the wealthiest countries.

- One potential reason why simple joys such as social interaction and experiencing nature play an outsized role in driving life satisfaction in small-scale communities is that many of these societies aren’t heavily monetized.

The Melanesian people living in the Roviana and Gizo regions of the Solomon Islands are some of the poorest in the world. They live a subsistence lifestyle, fulfilling their needs by fishing and farming. Occasionally, they sell their goods at the local marketplace to buy processed foods or pay their children’s school tuition fees. The luxuries of modern life — smartphones, the internet, TV, memory-foam mattresses — are hard to find. But despite this materially simple existence, the Melanesians express higher life satisfaction than residents of Finland and Denmark, who regularly make headlines as the happiest in the world.

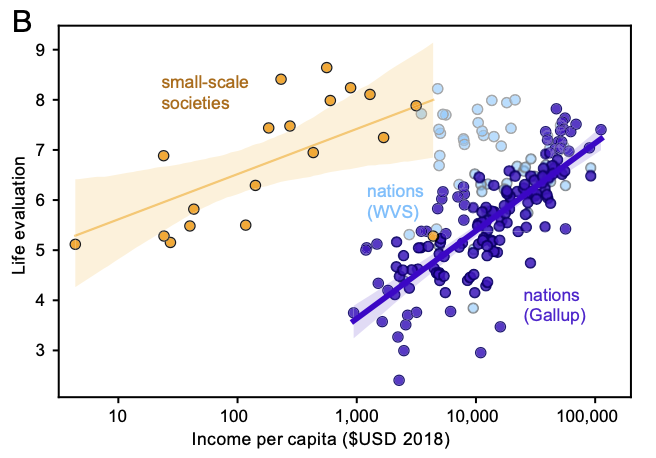

One of the most robust findings in happiness research is the link between income, wealth, and life satisfaction. The more money someone has, the more satisfied they tend to be. The richer a country, the happier its citizens. But as scientists are now learning, some buck this broad trend. People — often indigenous — who live in small, isolated communities tend to be as satisfied with their lives as people living in the wealthiest countries. Finding out why could benefit us all.

Wealth and life satisfaction

It was this aim that inspired new research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Scientists from Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona in Spain and McGill University in Canada traveled across the world to survey close to 3,000 members of 19 poor, small-scale societies located in 18 different countries. They visited Kumbungu in Ghana, Laprak in Nepal, Vavatenina in Madagascar, and Lonquimay in Chilé, among many other remote places. The scientific trek was primarily for a grander project concerning climate change, but the researchers also assessed subjects’ life satisfaction.

“The average reported life satisfaction among our 19 surveyed small-scale societies is 6.8 out of 10, even though most of the sites have estimated annual monetary incomes of less than US $1,000 per person,” the researchers reported. Life satisfaction values this high are typically only seen in countries where GDP per capita exceeds $40,000 per year.

So what explains this leap to a higher level of happiness? Western anthropologists who’ve visited small-scale communities have generally found that these people derive a great deal of satisfaction from simple activities such as listening to music, going for a walk, or just relaxing. Relationships with friends and family as well as socializing also bring lots of joy. Community members also tend to greatly value spending time in nature. Copious studies show that being outside in pristine, natural habitats boosts mood, health, and overall well-being.

An obvious potential reason why simple joys such as social interaction and experiencing nature play an outsized role in driving life satisfaction in small-scale communities is that many of these societies aren’t heavily monetized. In prior research, members of the same Barcelona and McGill team visited other small societies and compared their collective well-being. They found that in communities where money played a larger role, reported drivers of happiness shifted: People went from enjoying experiential activities in contact with nature to instead prioritizing social and economic factors. Money brought happiness rather than life’s simple pleasures.

The central takeaway, according to the researchers of the present study, is life satisfaction “does not require the elevated rates of material consumption generally associated with high monetary income.” Once peoples’ basic needs — like housing, food, and safety — are met, joy can be found in the people and places around us.