Game of Thrones Episode 4: Debt, Destruction, and Dragons

Bronn never feels like he receives his due. Then again, he’s always trying to milk whatever he can out of a situation. While Jamie reminds him he’s from wherever—meaning, low-caste—the sellsword has relied on his wit and negotiating power as much as his swordsmanship. When Jamie throws him a bag of gold he’s flabbergasted that Bronn expects a castle.

Jamie, manipulator he is, knows he is indebted to Bronn, and will be even more so by episode four’s end (if he survives the deep river in all that armor). While Jamie fends off a dragon, Cersei is negotiating her own debt, one the Iron Bank immensely enjoys collecting on. Those interest payments bring quite a smile to Tycho Nestoris’s mug.

Brandon Stark too owes debt, one he sidesteps by claiming he’s no longer Brandon Stark. His unemotional retort to Meera’s plea for acknowledgement ends with his claiming the ghost in the machine has fled; he is now fully the Three-Eyed Raven. Apparently ravens aren’t indebted to anyone, having transcended the silly world of human emotions.

Bran has long been developing the indoctrinating blank-eyed stare all wannabe gurus practice. Back in the human world, though, debt exudes an emotional quality. People expect debts to be paid. This fact has been the source of much contention for thousands of years, ever since written language began as a means for keeping track of livestock. Our very ability to write down thoughts stems from an accounting ritual.

So it makes sense that everyone wants what’s due to them. Yet at the same time, the issue of debt has severe consequences, including financial inequality and social stratification. Debt has also long been assigned with spiritual dimensions, as the oldest record keepers were inevitably tied up with religious institutions.

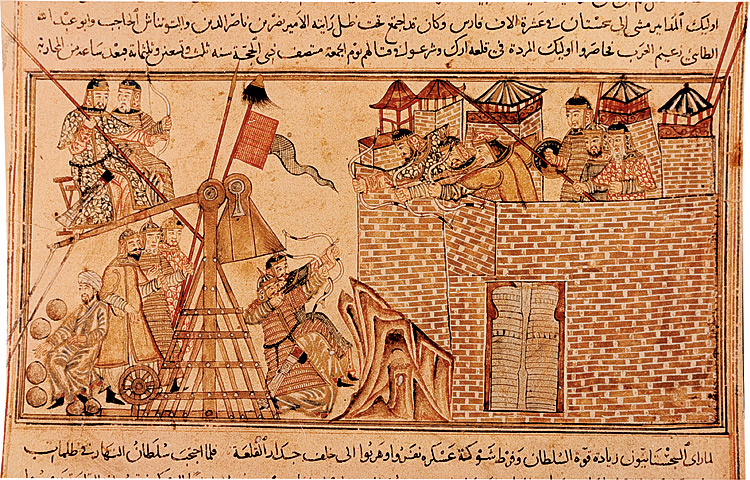

The major source of the debate is highlighted by Nestoris, who is giddy at the interest the bank has been collecting to fund her war. There is precedent. In the Republic Plato warned against the dangers of excess and luxury. Leaders in the luxurious city, focused on “the endless acquisition of money” that “overstepped the limit of their necessities,” had to pillage neighboring lands in order to keep feeding their destructive appetites, which is exactly what Jamie is out doing when he runs into the Dothraki. Plato, recognizing that we have to work hard at cultivating an equitable society, championed moderation as the keystone of sustainability. The healthy city does not over-consume. Westeros is not healthy.

Aristotle shared his teacher’s suspicion about finances. Specifically he was critical of usury, which he called “the birth of money from money.” He believed money is sterile; when it breeds it causes a blight on social relationships. As an extension of the bottom line psychology that began with written record keeping, wealthy merchants began charging interest on loans, overturning a history of shared debt indicative of tribal societies. Moneylending immediately assumed a spiritual dimension regarding individual and social rights.

In her book, Payback: Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth, Margaret Atwood calls debt a “mental construct.” Whereas today we consider it a regular if despised part of functioning society, she reminds us that the huge interest rates banks and credit card companies charge is a form of greed, not an inherent biological function, as is the notion of “trickle down economics,” which implies a slow drip, not a gush of wealth. She continues,

Everything in the human imagination and consequently in human life has both a positive and negative version, and if the trickle-down theory of wealth is the positive, the negative is the trickle-down theory of debt.

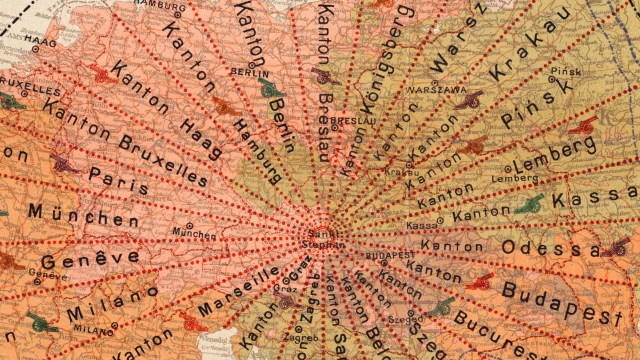

A century before Atwood, Hungarian literary historian and critic György Lukács coined the theory of “thingification,” reminding consumers capitalism and the market are malleable. Like Karl Marx, he believed capitalism is built on avarice and greed. The mounting debts consumers face due to the perpetual manufacturing of products keeps them enslaved to titans of industry. British economist John Maynard Keynes went so far as to claim that the love of money is a mental disorder.

Which, if true, means there are plenty of mental health problems in large banks and creditors today, as it has been shown that addiction to money is neurologically similar to cocaine addiction. The necessity of claiming debts even exceeds death, as families are often held accountable for money owed.

Though life has changed much since those first papyrus scrolls documented scores of sheep and cattle, our relationship to debt has only become more acute. The NY Timesrecently reported that the culture Venmo is helping create a transactional culture insistent upon a penny:

Venmo theoretically should make these relationships less obviously transactional. Yet not only does it encourage pettiness, distilling the messiness of human experience down to a digitally precise data point, but by making it so easy to pay someone back for purchases as trifling as a coffee, the app arguably promotes the libertarian, every-user-for-himself ethos of Silicon Valley.

Part of what makes humans human is our capacity for altruism: you pick the lice from my body today, I’ll do the same tomorrow. Debt, especially in regards to usury, is an exploitation of that system. There’s nothing wrong with wanting returned what you leant, but the psychology of debt often leads to something more sinister, less humane: a sense of ownership, be it of property or people, the two at times indistinguishable, as Cersei shows.

This feeling of entitlement destroys our humanity. Some even expect that the “universe” or society owes them something simply for being born, which is antithetical to healthy psychology. Instead of feeling gratitude for being the result of a long history of biological forces, our cortisol levels rise when a friend ignores an invoice for last week’s latte.

Television shows provide comeuppance in a way reality rarely offers, as they are written more to reflect our desires than what we actually experience. Arya’s list is getting short but she wants to collect on her debts. Daenerys is owed what she believes has been guaranteed hers thanks to bloodline. Brienne owes a debt to her deceased queen, as does Little Finger, by his own twisted and self-serving logic.

The entire series is a series of paid and failed debts, all constructions of the human mind’s need for retribution. In that quest our minds usually seek something more, a payment above what we’re owed. By that mindset the destruction and death we loathe and crave occurs. As long as we think we’re owed something we will never find the peace we think we desire.

—

Derek is the author of Whole Motion: Training Your Brain and Body For Optimal Health. Based in Los Angeles he is working on a new book about spiritual consumerism. Stay in touch on Facebook and Twitter.