Is the U.S. becoming more paranoid?

- Social paranoia is more common than its clinical counterpart.

- However, its causes are different, ranging from the prevalence of crime-obsessed media to ontological insecurity.

- Contrary to popular belief, America isn’t becoming more conspiratorial.

In 2015, a high school student from Texas named Ahmed Mohamed was taken into custody after a teacher mistook his homemade clock for an explosive. This event, however bizarre, was not unprecedented. Two years earlier, residents of Tyler — again in Texas — were evacuated from their homes as federal agents “dismantled” yet another science project, this one made by a local 8-year-old.

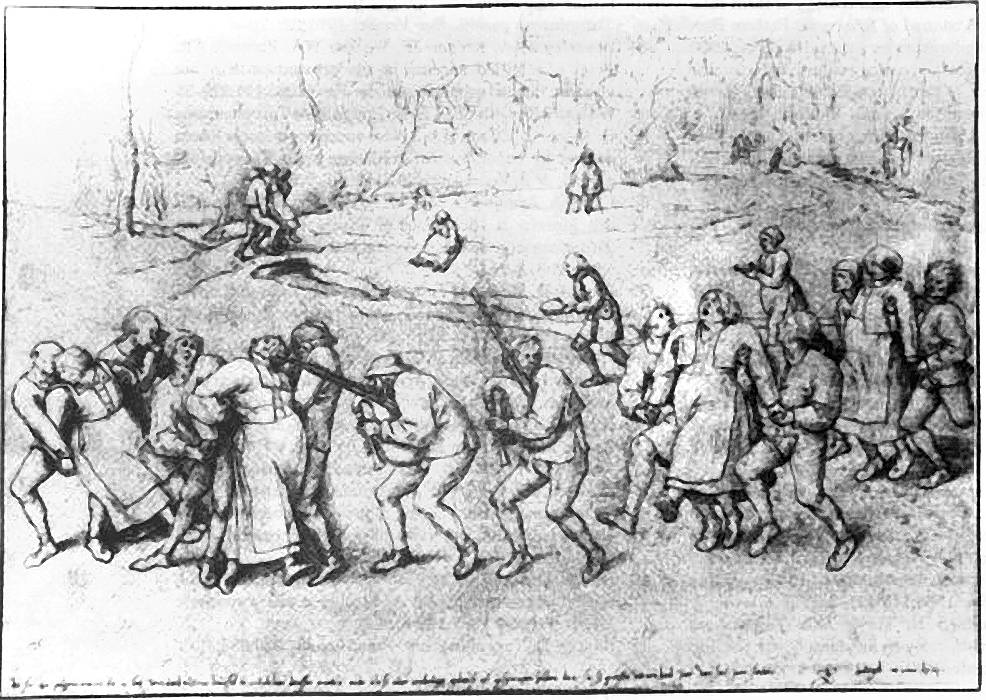

Today, stories like these are often cited as proof that American society is becoming increasingly paranoid — an assessment that is itself becoming increasingly widespread, not without reason. As a social phenomenon, paranoia does indeed appear to be more common than its clinical counterpart. “Madness,” Friedrich Nietzsche famously declared, “is something rare in individuals – but in groups, parties, peoples, and ages, it is the rule.” In a collective, it finds expression in conspiracy theories, mass hysteria, and — at times — even mass psychogenic illness.

Although social paranoia is not a form of mental illness and does not arise from imbalances in brain chemistry, its effects on our quality of life — let alone the quality of our social institutions — can be just as detrimental. Take, for instance, perceptions of crime and safety. “Research has consistently shown that when you ask people in the United States if crime is going up or down, the majority will say it’s going up,” Lisa Kort-Butler, a sociologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, told Big Think. “But when you map that out against actual crime rates, it’s not true — not in the last couple decades, at least.”

This, Kort-Butler stresses, is no trivial observation. When we misjudge the prevalence of criminality, we also misjudge the risk of ending up as one of its victims — an error that influences decisions big and small, from whether or not we move to a different city, take public transport to work, or report a student to the police for going above and beyond on his homework assignment.

The causes of social paranoia

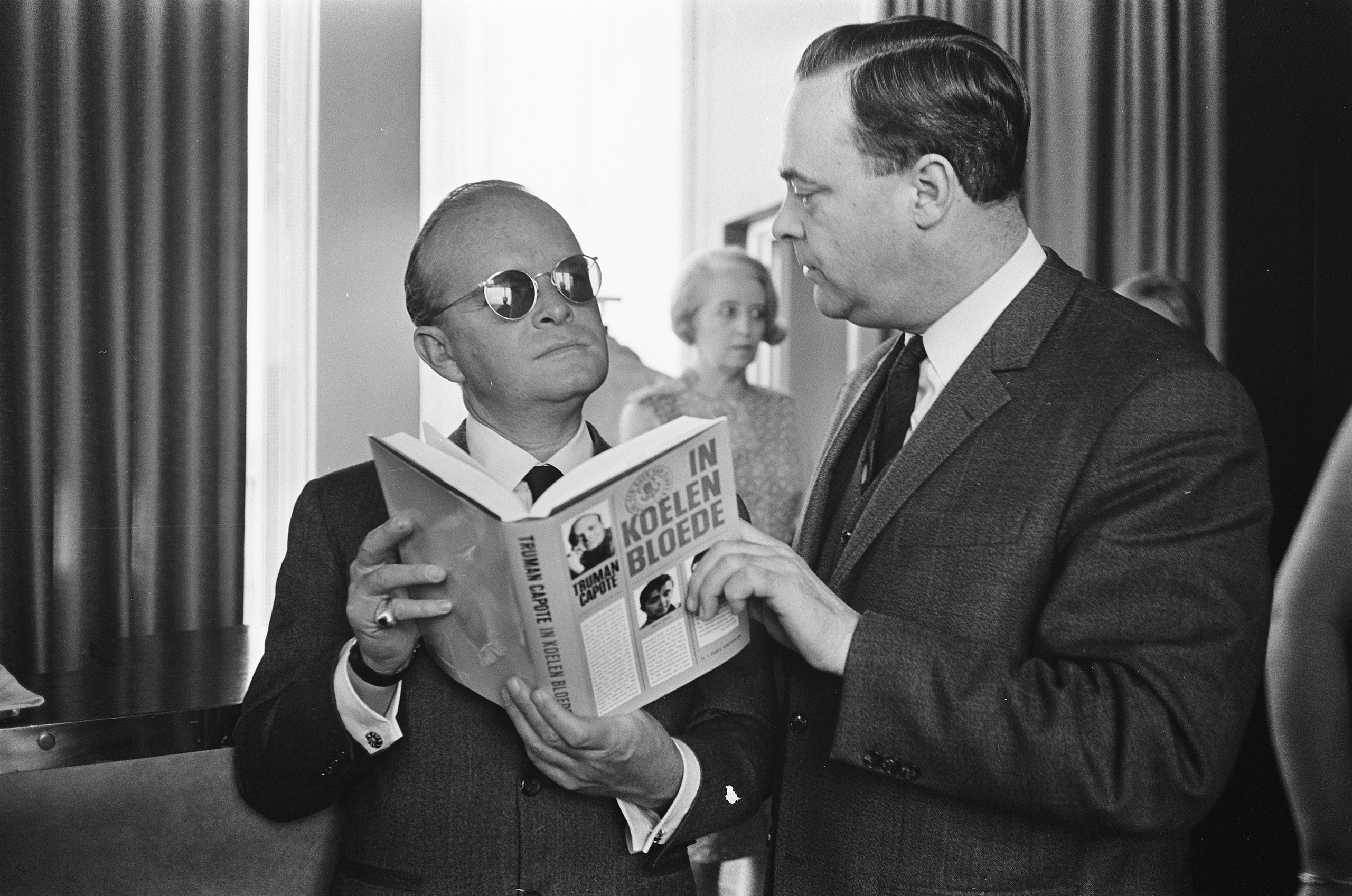

One well-known contributor to social paranoia is the media we consume. News outlets give more attention to negative than positive events, a strategy that boosts viewership but also presents a misleading worldview. True crime, popularized by bestsellers like Truman Capote’s 1965 novel In Cold Blood and optimized by the current generation of streaming service documentaries about serial killings, kidnappings, and other forms of rare and ultraviolent crime, takes advantage of our morbid curiosity — the irrational urge to obsess over that which makes us uncomfortable and deeply afraid.

Crime-obsessed media can fuel paranoia in a number of ways. “What people are willing to believe is closely related to the narratives they see,” Jesse Walker, books editor of Reason and author of The United States of Paranoia: A Conspiracy, told Big Think. “One thing I discussed in my book is how the revelation of real-life conspiracies in the wake of Watergate and so on was followed by waves of conspiracy thrillers in Hollywood,” creating a positive feedback loop.

Media, adds Kort-Butler, “doesn’t cause people to think X or do Y, but it certainly limits what we can know. Most people do not go and look at actual crime statistics, let alone know how to evaluate them.”

However, while the things we watch in our spare time certainly contribute to social paranoia, they should not be mistaken for its root cause. “The media produces content that’s the most attention-grabbing,” she continues. “It is a business model. Ultimately, though, we are the ones concerned with these rare, horrible events. To say the media is responsible and they’re the problem oversimplifies the relationship.”

The root of the problem

Kort-Butler learned to look beyond media when analyzing public discourse surrounding Todd Phillips’ 2019 film Joker, which reimagines the infamous Batman villain as a mentally ill member of the working class. At the heart of this discourse was the protagonist’s resemblance to real-world criminals like incels and mass shooters, indicating that the film’s popularity was based not just on its inherent quality, but also on its relevance to current events and society’s preexisting opinions about them.

Walker can think of at least two underlying causes for social paranoia, neither of which involve the media. The first of these causes has to do with security, or rather the perceived lack thereof. “When people have a general sense of insecurity — called ontological insecurity, a sense that the world is not right, that I don’t know what’s going on and feel powerless to do anything about it — then feelings that do not seem to have a clear source can be channeled into attitudes about crime and other dangerous things.”

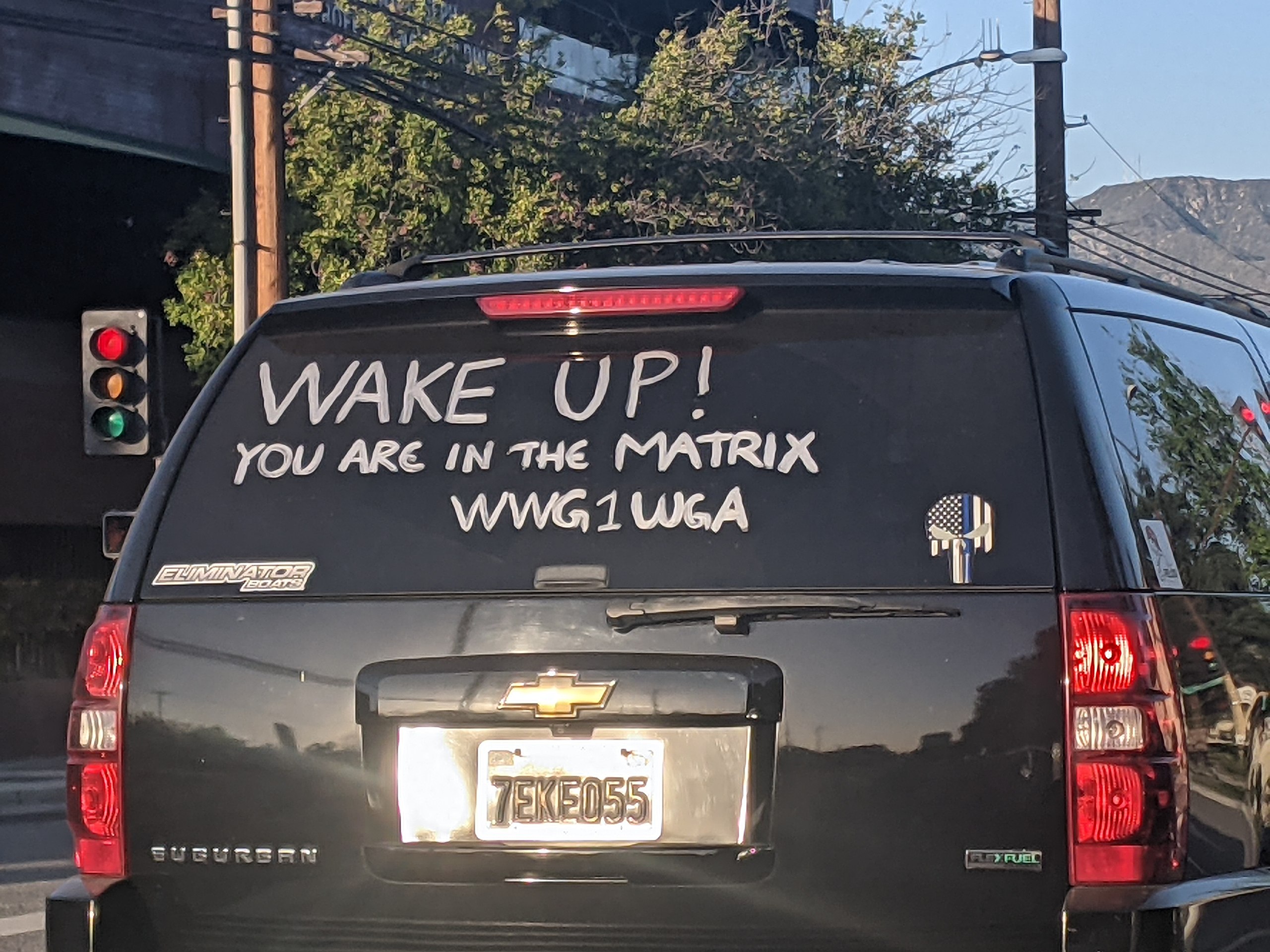

The second cause, related to the first, centers on empowerment. “People become attached to conspiracy theories because they feel empowered by them,” Walker continues. “They feel that they have found the true knowledge and that they know something others don’t. They become disengaged from their social network and engage with another that confirms their feelings, their line of thinking.”

In this case, the term “conspiracy theories” doesn’t just encompass well-known plots such as Pizzagate or 9/11 as an inside job, but also misconceptions like the overestimation of crime patterns. In both cases, the adherents believe they have detected a threat that those around them are ignoring, providing them with a source of both validation and concern.

Curing the ailment

Unlike its clinical counterpart, social paranoia cannot be remedied with therapy and medication. That said, basic awareness of the phenomenon can go a long way to disarming its negative effects. Kort-Butler turns to a familiar adage: Think critically about where your information comes from. “We have to teach people how to become better consumers,” she says, adding that we should call true crime documentaries by their true name, namely a form of fake news — something that pretends to be accurate and realistic while actually being a partial invention.

Walker urges readers of United States of Paranoia to familiarize themselves with the fixed set of narratives conspiracy theories can assume. These formats include the “enemy from above” (i.e. the deep state, the Illuminati), the “enemy from within” (the domestic terrorist, the spy), and the “enemy from outside,” (the rival nation). Today, thanks to a series of government failures like the War on Terror, Americans appear to be most susceptible to enemy-from-above narratives, explaining the virality of Pizzagate, Qanon, and Donald Trump’s repeated promise to “drain the swamp.”

It’s equally important to recognize that these narratives appear and reappear with each new generation. “A decade ago,” says Walker, “there were articles observing how the fear of cults had gone away, and the storyline retreated to the margins of society. It came roaring back in the late 2010s due to fascination with historical events like Jonestown and communes. There was a tendency to use the cult framework to make sense of other things going on.”

Often, concerns that appear novel and unique are really cobbled together from older, forgotten theories:

“Everything people in the Q-world believed existed in earlier conspiracy stories. There’s stuff from the 1990s that sounds identical to Pizzagate and other theories from the last decade, but with different leaders. Back then, they were Henry Kissinger’s sex slaves instead of Tom Hanks’ or Hillary Clinton’s.”