Why this startup is creating edible oil from sawdust

- Palm oil production hurts the environment and biodiversity, but it’s difficult to replace due to its remarkable productivity.

- The Estonian startup ÄIO has developed a process to make fatty oils with yeast that thrive on sawdust.

- Its founders hope the technology will replace palm oil and promote local economies to be more circular and sustainable.

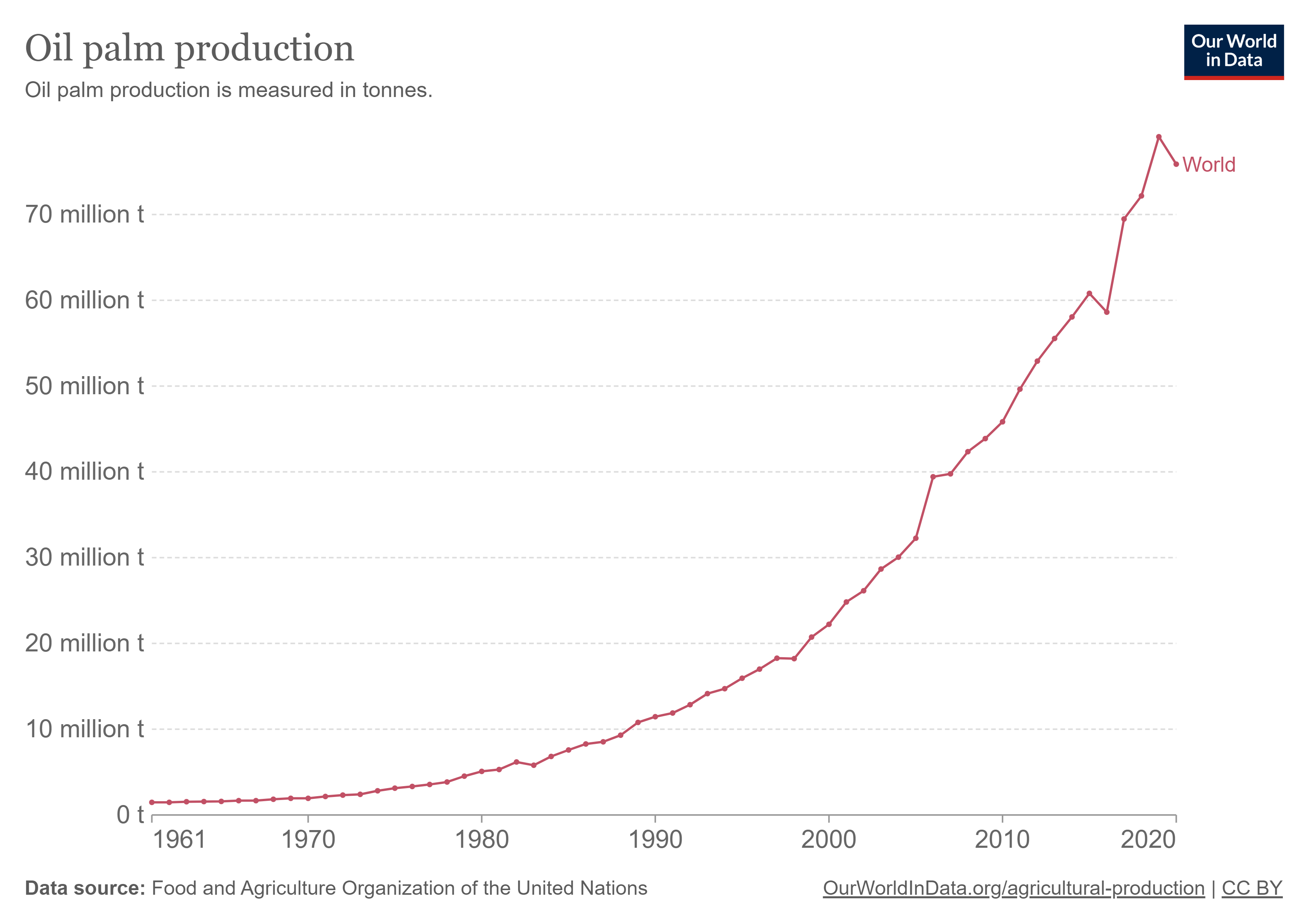

Just because something is natural doesn’t necessarily make it sustainable. Consider palm oil. The product was widely adopted in the 20th century to replace purportedly less healthy oils and fats in foods. Odorless, semi-solid at room temperature, resistant to oxidation, and — most importantly — cheap, it’s now found in almost everything.

In fact, the World Wildlife Fund estimates that 50% of all packaged products contain palm oil. It’s in chocolate, pizza dough, and margarine. It’s also in cosmetics like lipstick, and personal care products, such as deodorant, shampoo, and toothpaste. We use it in cleaning products, in pet foods, and as a biofuel. The list goes on.

To meet the soaring demand, businesses around the world but especially in Southeast Asia are clearing tracts of rainforest to make room for palm oil plantations. The loss of such biodiverse habitat not only threatens close to 200 species, including the orangutan, it also throws millions of tonnes of greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere (to say nothing of the industry’s well-documented worker exploitation).

Unfortunately, boycotting the product may not be a realistic option either, as the readily available substitutes may prove environmentally worse.

That’s because palm trees are remarkably productive. They create 2.94 tonnes of oil per hectare of land, far outpacing other vegetable oils. Sunflowers produce just 0.74 tonnes of oil per hectare, soybeans 0.46 tonnes, and coconuts a meager 0.23 tonnes. To maintain the current supply with these alternatives — to say nothing of increasing demand — would require dedicating vastly more total land to oil production.*

Rather than growing existing alternatives, it may prove more efficient to invent a new one. Estonian biotechnology startup ÄIO is doing just that.

A whole different yeast

ÄIO was founded in 2022 by Petri-Jaan Lahtvee and Nemailla Bonturi, a professor and senior researcher of food technology and bioengineering at Tallinn University of Technology, respectively. The two were initially part of a research group led by Lahtvee looking into biotechnology processes that relied on locally available resources.

After a year and a half of building and studying various processes, one stood out as special: a yeast created by Bonturi.

Conventional yeast are microorganisms that consume raw sugars from organic sources like corn, barley, or fruit. Through metabolism, they then convert sugars into various end products known as metabolites. And these are key to many of our favorite foods.

For example, baker’s yeast releases CO2 as a metabolite, and this is why bread rises. In beer brewing, yeast metabolizes sugars into CO2 and alcohol (more specifically, ethanol) during the fermentation stage.

Bonturi’s yeast works similarly; however, hers evolved to be robust and productive with raw materials far more challenging than corn. Her microorganisms can consume the sugar found in even sawdust and metabolize it into lipids chockablock in antioxidants and omega-3 — the building blocks of the animal fats and plant oils we eat every day.

This unorthodox yeast was nicknamed “the red bug” after the ruddy pigmentation of the resulting biomass. (Though Bonturi admits, the moniker is also a nod to her three favorite “Red Queens” — the character from Through the Looking Glass, the AI from the Resident Evil series, and the Red Queen hypothesis in evolutionary biology.)

“This microorganism was ‘architected’ by cultivating it through different selective pressures and letting nature do the work,” Bonturi said in an exclusive interview with Freethink.

She and Lahtvee then developed a fermentation process, one similar to brewing beer. They mix the red bug in large, stainless steel tanks with the sugars from sawdust or other upcycled organic sources. They add some heat to activate the yeast and let the microorganisms do their thing. Once fermentation is complete, they harvest and treat the lipid-rich biomass to create food-grade oil- and fat-alternative products.

ÄIO is currently focusing on three bespoke products. Its RedOil could be used as an alternative to vegetable and fish oils, or serve as a substitute for synthetic ingredients in cosmetics and lubricants in household cleaners. The company produces a powdered form for easy transportation and a “buttery fat” to replace lards and shortenings, as well.

“Our main goal is to replace palm oil,” Lahtvee said in the interview. “At the same time, we are working with precision fermentation of specialty lipids so that we can provide the chemical and physical properties that a customer needs, such as a specific melting temperature or taste profile.”

Think globally, act locally

ÄIO’s biomanufactured approach has several potential advantages over palm oil. For one, its powdered form can travel without risk of leaks, spillage, and loss. It can then be reconstituted on-site and emulsified to provide the consistency required for whatever product it is used in.

The yeast can upcycle “side streams” from many different industries, too. Side streams are the unwanted, low-value byproducts of industrial activities — think sawdust from lumber or weeds from agriculture. While ÄIO has focused mainly on sawdust, its versatility means the fermentation process can be implemented locally anywhere a compatible side stream is available.

Our technology contributes to the circular economy because it allows us to upcycle low-value products.

Petri-Jaan Lahtvee

“Our technology really contributes to the circular economy because it allows us to upcycle low-value products,” Lahtvee said. “It’s important to ensure food security, as well. Because our processes don’t rely on long supply chains, and you don’t have to transport specific goods to certain places, they can be locally produced.”

Finally, there’s the advantage of speed. It takes time to clear a dense rainforest, build a plantation, grow the palm trees, harvest the palm fruit, and then process it. The same can be said for raising animals for butter and lard. Conversely, microorganisms like yeast live on a far speedier time scale. This means ÄIO’s fermentation process has the potential to produce fats and oils far quicker once production is at scale.

All told, if RedOil replaced palm oil, Lahtvee and Bonturi estimate that their technology has the potential to “reduce land use by 74–97% and cut water consumption by up to 10 times,” as well as significantly curb greenhouse gas emissions.

Food for thought

ÄIO is currently testing its products in the food industry — where two-thirds of all the palm oil produced is currently used. The company is specifically targeting plant-based meat alternatives, where their oils and fats have the potential to deliver the same taste and mouthfeel as animal fats, something that vegetable oils don’t imitate well. It is also fundraising and fostering new partnerships.

To scale production, Lahtvee and Bonturi have constructed a small plant. The plant will begin producing 20 kilograms of fats and oils a week by the first quarter of 2024. This will hopefully demonstrate that the process is robust enough for industry-like conditions. Looking ahead, Lahtvee and Bonturi are in the pre-engineering phase for a demo plant, which would increase production to more than 750 tonnes a year. They hope the plant will be operational by 2026.

As always with a young company, challenges lie ahead. As Bonturi pointed out in our interview, new variables might arise when scaling up, and they’re working to prepare for them as best they can.

The company is in the process of applying for a novel food permit with the European Union. EU regulation defines any food “that had not been consumed to a significant degree by humans in the EU” before May 1997 as novel — anything from a biomanufactured enzyme to chia seeds. The regulation requires novel foods to be evaluated for consumer safety. A laudable goal, but a time-consuming process.

“The novel food permit is a challenge because it takes about three to five years for certification in the European Union,” Bonturi said. “Laws that would help startups like us innovate faster and get to market quicker would be helpful. Because if you want to save the planet, we are already late.”

But the steepest challenge may simply be the status quo. People are creatures of habit, and perhaps nowhere else is this more pronounced than in something as personal, familiar, and culturally important as food. Convincing people to adopt an unconventional food will be no small ask. But looking toward our health and the sustainability of the planet, it’s an ask we should be willing to consider.

“We are consuming food every day, and quite often, we don’t realize the economic or environmental burden of it. I hope people will look more at what they eat and how sustainable it is while also being more curious whether innovative products can actually be healthier and tastier for them,” Lahtvee said.

* With that said, the comparison isn’t exactly one-to-one. As Hannah Ritchie points out at Our World in Data, the impact of devoting a hectare of farmland to sunflower seeds in Europe is not the same as burning a hectare of tropical rainforest in Indonesia for palm trees.

This article was originally published by our sister site, Freethink.