Life on Mars: Why it matters. What it means.

Last week we took one important step closer to knowing if Mars was, or still is, a living world.

In a remarkable paper in the journal Science, a team of NASA researchers reported that the Curiosity rover had found evidence for organic chemistry on the Red Planet.

In an equally significant development, scientists also reported finding background levels of methane, one of the most basic organic compounds, varying with the Martian seasons. The news made headlines across the world.

But what do these findings really mean?

First off, it’s important to note that “organic chemistry” doesn’t necessarily mean chemistry from organisms. An “Intro to Organic Chemistry” class would tell you that it is, fundamentally, chemistry involving carbon. Carbon is pretty common in the universe, and it has an amazing chemical affinity for combining with other stuff, especially hydrogen and oxygen—the essential ingredients of water.

So all this means you can have organic compounds without having life. Full stop.

On the other hand, life as we know it makes very good use of organic chemistry, and that’s why last week’s news was so exciting. The discovery of organic compounds locked up in rocks indicates that Mars once had a chemical environment that was, at least, conducive to life.

Which means that the news represents another (positive) step toward seeing Mars as a world that may have had life. And if you consider the history of our imaginings about Martian life, you can see why these steps matter so much.

In my new book Light of the Stars: Alien Worlds and the Fate of the Earth—which releases today—I examine the history of how Mars and life go together in our cultural and scientific imaginations. It’s a story that might best be called the “Red Planet Shuffle.”

Speculation from the 1800s

As early as the 1800s, astronomers studying Mars knew it had surface features that changed over time. This led many 19th century scientists to a dramatic conclusion: Mars had a climate like our own. They saw seasons in the form of white polar caps that grew and then retreated as the planet tracked through its 687-day orbit. So it was with good reason that by the 1870s, astronomers like Camille Flammarion—the Neil deGrasse Tyson of his day—envisioned Mars as a world rife with organisms.

Then, at the turn of the 20th century, the wealthy amateur astronomer Percival Lowell claimed that Mars was crisscrossed by long straight structures called canals that were, for him, a clear indication of an intelligent civilization at work. While most astronomers dismissed Lowell’s observations as wishful thinking, in the popular imagination the die had been cast. Through books like H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, Mars became the place most people imagined to host an alien civilization.

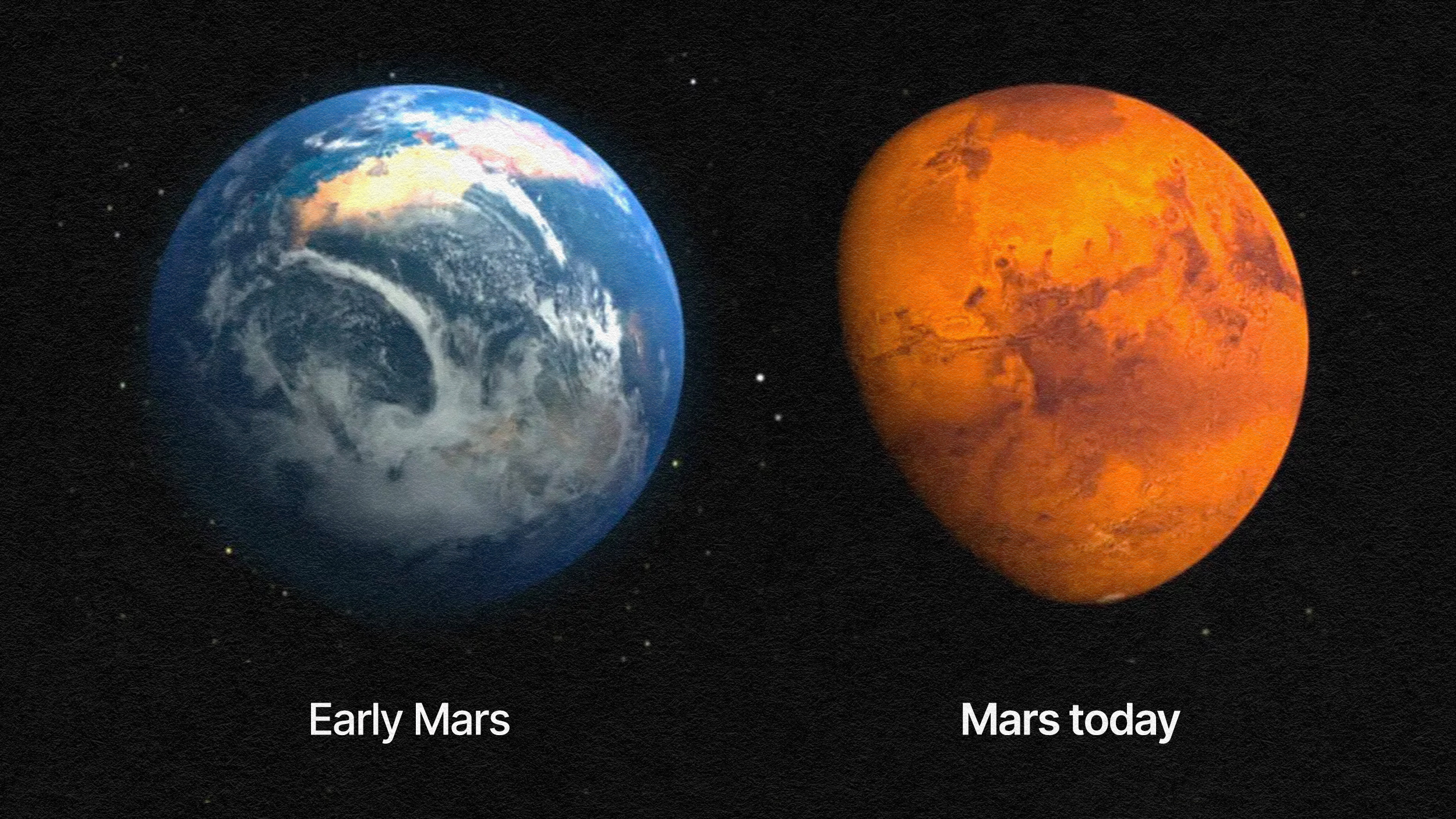

But by the mid-20th century, astronomers had already accumulated enough telescopic evidence to be confident that Mars was not home to an advanced civilization. Still the possibility that life in some form existed on that world was still very real. Periodically the planet experienced significant changes in color that some argued had a biological origin. Then, in 1965 the U.S. space probe Mariner 4 sailed past the Red Planet, and with just 22 images it killed the dream of life on Mars in both the public and scientific imaginations.

It was the craters that did it

Mariner 4 saw a lot of craters on Mars. On Earth, craters don’t last long because of weathering. Seeing large craters on Mars meant its surface hadn’t changed in billions of years. Mariner 4 showed us a Mars that looked a whole lot like the empty desiccated moon. As a New York Times editorial told its readers:

“The astronomers of past decades who thought they detected canals on the Martian surface and speculated that it might have bustling cities and beings engaged in lively commerce were victims of their own fantasies . . . The red planet is not only a planet without life now, but probably always has been.”

Luckily, Mars didn’t stay dead for long. In 1971, Mariner 9 went into orbit around Mars, and its thousands of pictures showed something remarkable—landscapes that looked a whole lot like they’d been carved by flowing water. There were dry riverbeds, broad deltas, floodplains and rainfall basins. Mars might look dead now, but its past suddenly seemed very different.

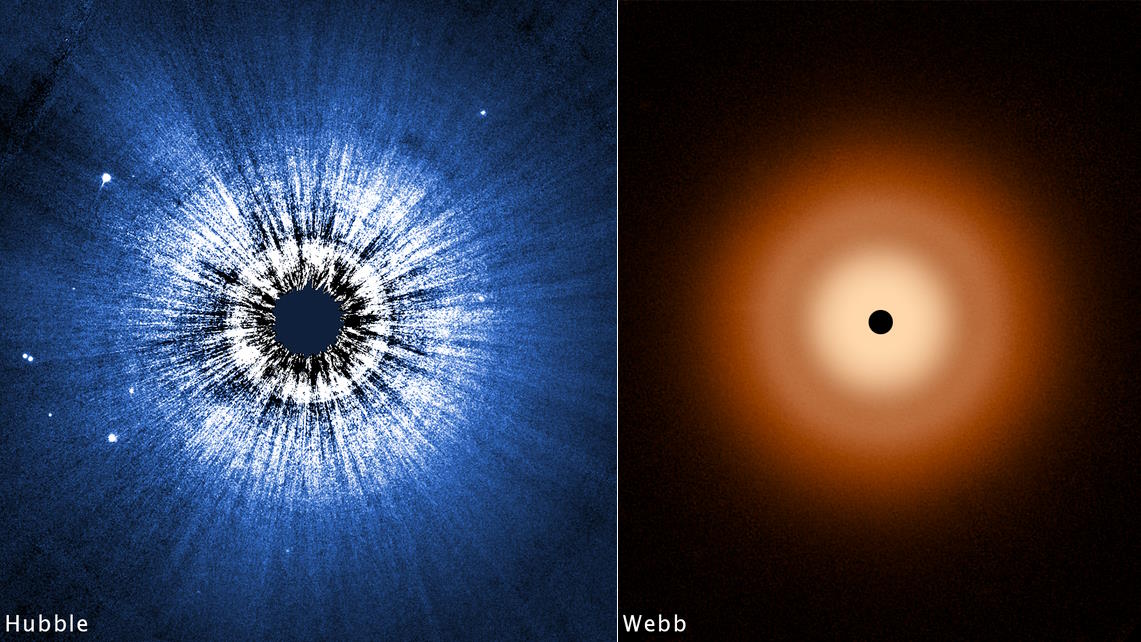

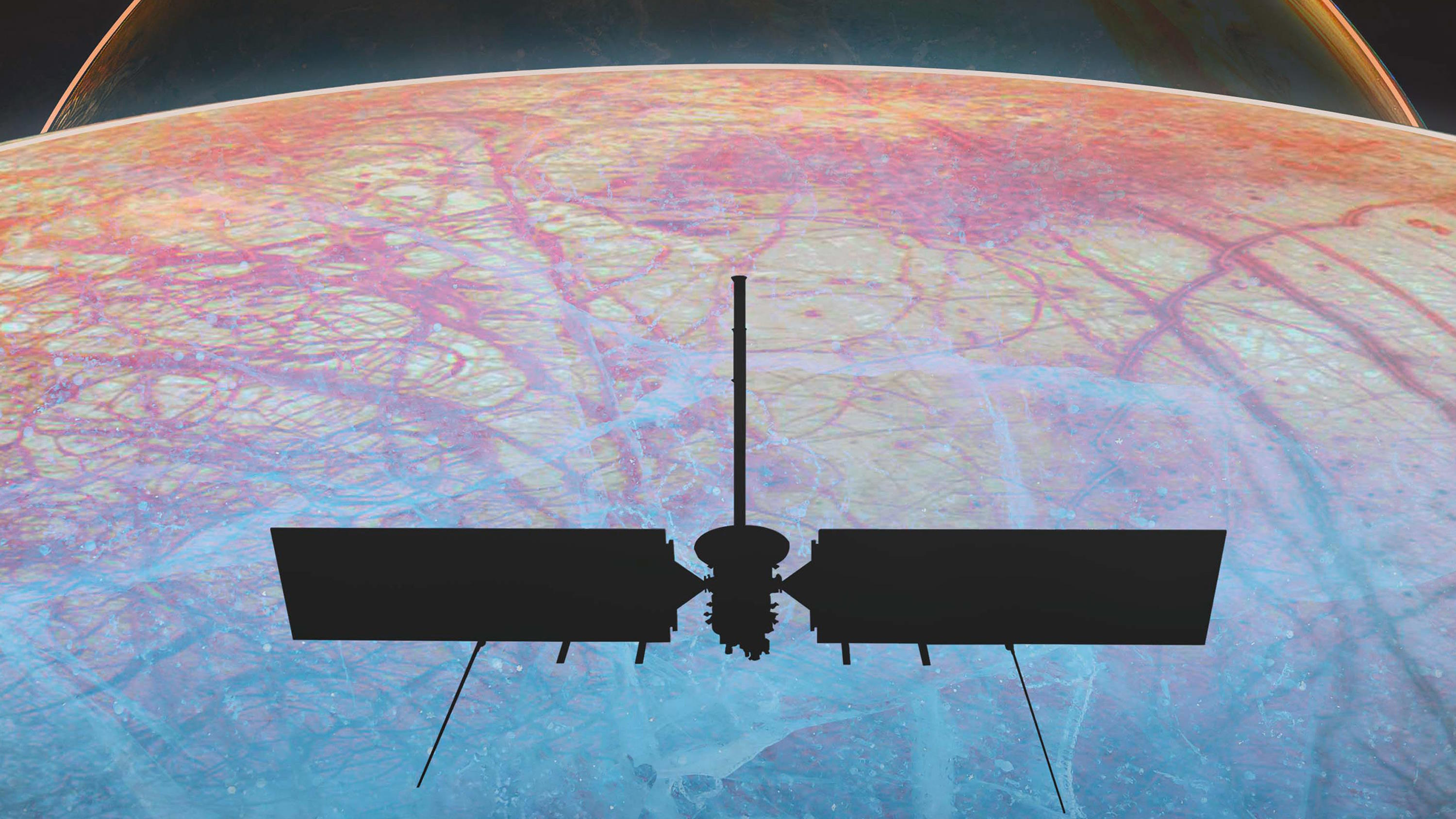

Over the last 20 years we’ve sent a small flotilla of space probes, landers, and rovers to the Red Planet, and they’ve confirmed what Mariner 9 hinted at: Mars used to be a wet planet. And since we believe water to be essential for life, that firm conclusion leads to the next essential step: Look explicitly for evidence of life now or in the past. That’s why last week’s discoveries were so important.

Biochemistry = meaning

So why would it matter if we find evidence for microbial life on Mars? The simplest reason is the most profound. It would tell us that, on an essential level, Earth is not unique. As of today, we don’t yet know if life is a one-off accident in the cosmos, or if it is an essential player in the drama of the universe’s evolution.

This matters because once biological evolution kicks in, the universe gains the possibility for innovation, creativity, and meaning on levels that are impossible in a purely abiological cosmos.

The word “meaning” is especially important to consider here. Even the simplest one-celled organisms bring meaning into the universe in the sense that they respond to their environments in purposeful ways. When microbes swim up a chemical gradient looking for food (chemotaxis), they certainly are not thinking about what they are doing. But they are responding in a meaningful way to their environments. They sense which direction is important for survival and they act on that sense. In this way their biochemistry, hardwired as it is, creates the rudimentary conditions for “meaning making.”

Of course, with the advent of more complex organisms and perhaps nervous systems, that “meaning making” becomes more complex. Eventually it may even become symbolic as it did with humans.

So evidence that even simple life emerged on Mars would shatter the idea that we are “alone” in an essential way . . . because meaning would have emerged in in the universe more than once.

The post Life on Mars: Why It Matters. What It Means. appeared first on ORBITER.