How Asia is pivoting away from the U.S.

The Obama Administration famously proclaimed a ‘Pivot to Asia’, re-balancing America’s foreign policy away from Europe and the Middle East towards East Asia, the region predicted to lead the world in economic growth for the foreseeable future.

Some consider it Obama’s greatest foreign policy blunder: through neglect, the United States saw its position weakened in Europe and the Middle East, while its focus on East Asia alerted the suspicion of China, also weakening America’s hand.

“(The pivot) seem(ed) to Beijing like an effort to contain China militarily”, writes The Diplomat. “This led China to respond by becoming more aggressive, helping to undo the general tranquillity that existed before 2008.”

As demonstrated by President Trump on his recent trip to Europe, the current U.S. Administration seems happier to pursue fleeting photo ops with strongmen than to cultivate long-standing alliances. Where does that leave American influence in Asia?

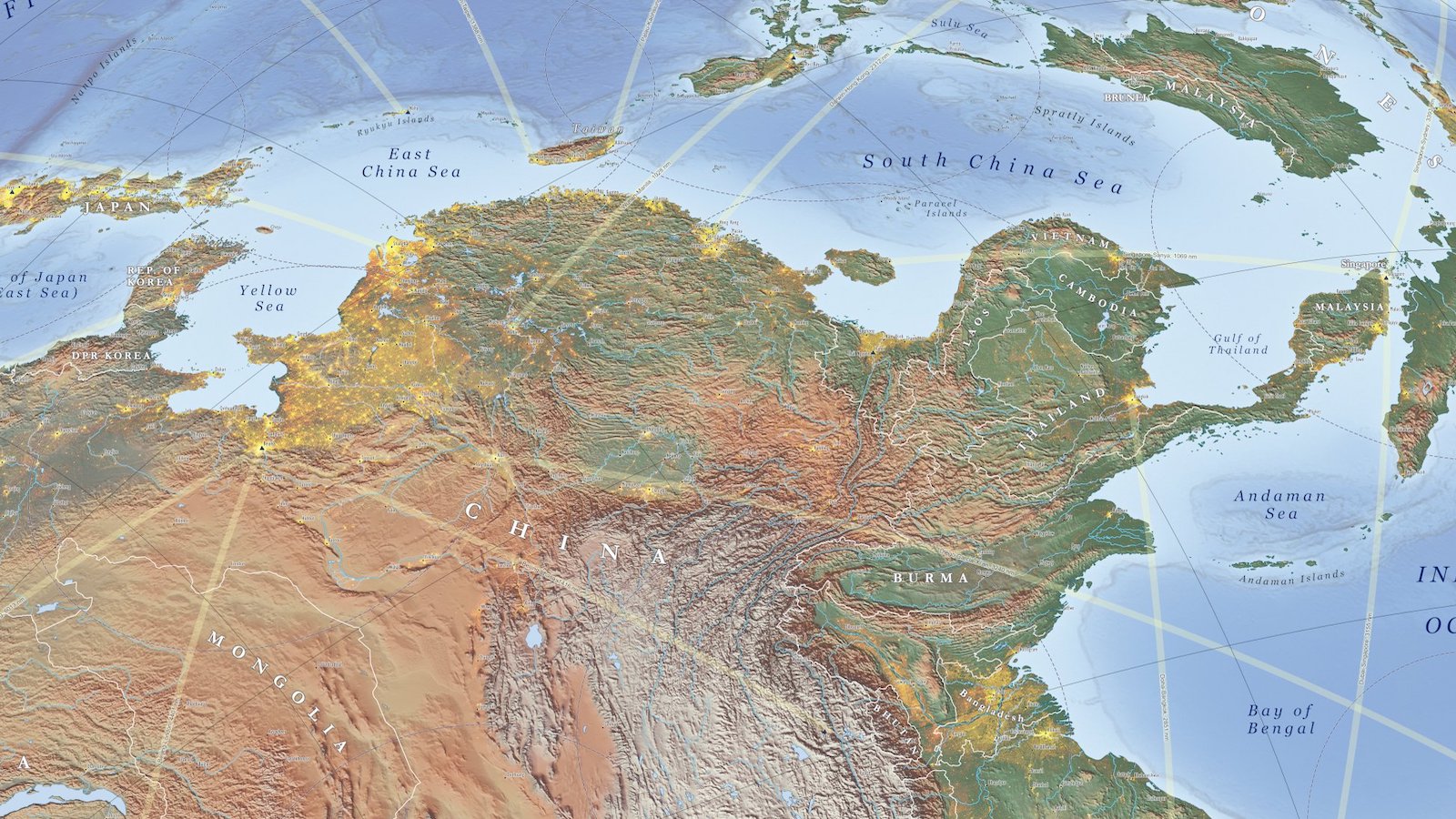

In short: on the wane. This map neatly captures the region’s resulting geopolitical fractures. Caught between a superpower (the U.S.) and a rising power (China), East Asia’s countries are doing some pivoting of their own: towards Beijing, towards Washington, or towards both.

In red, seven countries edging closer to China.

These include Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Nepal—not coincidentally four countries surrounding India. China’s long-term aim is to ring-fence its biggest rival in Asia with countries that are more beholden to Beijing than to New Delhi. Other China-leaning countries: Laos, Cambodia and Malaysia.

In blue, seven countries who would rather keep the Americans close in order to keep the Chinese at a distance.

These include a quartet of stalwart American allies: Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Australia; but also a trio of newer friends: India, Bhutan and Vietnam.

In green, five countries hedging their bets, playing Americans and Chinese against each other to obtain advantages from both—while attempting to maintain their autonomy from either.

This category both includes countries formerly firmly in the American column, such as Indonesia and the Philippines; and North Korea—Beijing’s only real ally, but eager to extract concessions from the U.S. all on its own. Also in the green column: Myanmar and Thailand, two countries dithering between democracy and military dictatorship.

The map accompanies a New York Times analysis piece which admits that, as China’s regional standing rises and America’s influence declines, the reality on the ground may not remain as neat as the one described by the red, blue and green on this map: “This is another possible future: countries subject to influence from both powers, with American and Chinese hands on their economies and politics. It’s a future that is both American and Chinese, with nations in the middle neither fully independent nor clearly aligned.”

Strange Maps #923

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].