A new study finds infants can discern between leaders and bullies

Researchers have just discovered that infants can determine the difference between a bully who coerces people into obedience and a leader who utilizes respect to encourage people to follow them. They also found that the infants have certain expectations of what people facing bullies or leaders will do next.

Even infants know a good leader when they see one

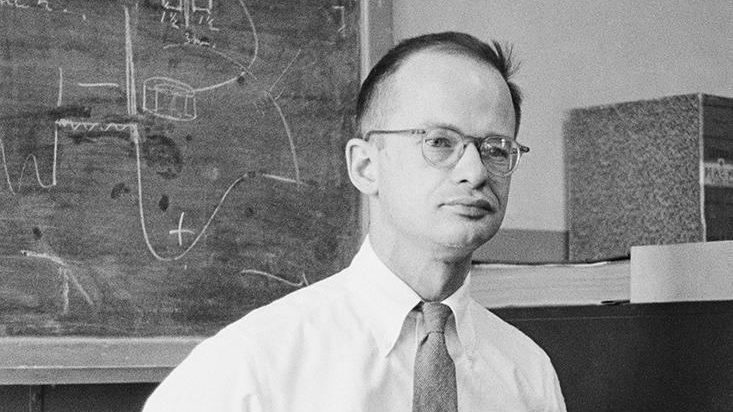

Francesco Margoni, a postdoc at the University of Trento, professor Luca Surian at Trento, and professor Renée Baillargeon of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign carried out the study with a group of 21-month-old children using a series of cartoons.

The first test’s cartoons showed a bully coercing other characters into action and then featured a respected leader instructing people to do the same thing.

The cartoons indicated that the bully was mean and that the leader was respected before any other action took place. The bully was identified by showing them striking the characters and stealing their ball, while the leader was bowed to and given the ball as a gift.

The cartoon introduced the leader or bully (yellow) by showing them either being respected by the red characters or attacking them with a stick. The first test featured a large headdress on the yellow figure which was removed or altered for later tests. (Margoni et al. provided by Dr. Baillargeon)

The second half of the cartoon showed the characters going to bed, as the bully or leader told them to do. The bully or leader then left. The cartoons then either showed the remaining characters staying in bed or getting up as soon as the authority figure was gone.

For the test, the yellow figure, now identified as a leader or bully, would command the red characters to go to bed. After the yellow figure left, the red characters would either continue to obey or immediately go back to playing. The responses of the children varied accordingly. (Margoni et al. provided by Dr. Baillargeon)

In studies such as this one, the very young children tend to look longer at an unexpected event before their attention span gives out—as opposed to an expected happening. By comparing how long they spend looking at each cartoon, the researchers can determine what the toddlers were expecting to happen.

As predicted, the infants expected the characters sent to bed by a leader to continue to obey after the leader was gone and paid more attention to the case where they left bed immediately. They were equally as interested in both cases with the bully, however. This suggests that they thought both outcomes were plausible as it was reasonable to take steps to avoid being hit again.

Size doesn’t matter

A second experiment was undertaken to confirm the first, and account for issues of interpretation. Since it is known that infants expect larger individuals to win confrontations, the headdresses of the leader and bully were removed to assure that the larger size of the characters didn’t influence the infants’ expectations.

The results were the same; the children expected a leader to be obeyed in their absence and were split on their expectations on if a bully would be obeyed or not after they left. It suggested that the children were able to distinguish the difference between the two based on behavioral cues and had different conceptions of how they acquired and used power.

It’s nothing personal

The final test sought to prove that power dynamics were the key factor in the infants’ expectations by removing the behavioral cues that one character was a leader and one was a bully and replacing them by showing all the characters positively or negatively interacting before the command to go to bed was given.

To determine if the children were thinking that the obedience to the bully was based on an expectation of further harm in the previous tests, the character who they negatively interacted with, essentially still a bully, remained on screen after ordering them to bed in this test.

It was found that the infants expected the characters to leave bed the moment the character who they positively interacted with went away. They also, however, fully expected the characters to stay in bed when the bully was still present on the screen. This supported the idea that the children who expected the characters to obey the absent bully in previous tests supposed that they might come back.

What does it all mean?

Infants expected cartoon characters to obey a leader they respected and were surprised when they did not. They only partly expected the characters to obey a bully, suggesting that while they understood that the characters didn’t respect the bully that they also grasped the idea of continuing to obey out of fear the bully might return.

It seems that if you want people to follow you even when you’re gone, respect works better than fear. Take that, Machiavelli.

What does this mean for how we view authority?

The study suggests that even very young children have an idea of legitimate authority and expect people to do what authority figures tell them. The idea that we have an innate moral psychology and that an understanding of authority is part of it remains a controversial topic.

Johnathan Haidt has written on the subject extensively and suggested it exists. Others disagree, suggesting that our minds are more like blank slates and that any understanding of authority we have must be learned.

The researchers summarized their findings on the matter:

“…our finding that infants expect leaders to be obeyed supports the prior claim by social scientists (e.g., Alan Fiske, Haidt and Graham) that the basic structure of human moral cognition includes a principle of authority: When an individual is acknowledged as a legitimate authority figure by a group, expectations come into play about how the authority figure should act toward the subordinates (e.g., maintain order), and about how the subordinates should act toward the authority figure (e.g., obey their directives). By demonstrating that infants can identify a respect-based leader and expect subordinates to obey this leader, we are one step closer to demonstrating that a principle of authority is indeed part of the basic structure of human moral cognition and emerges early in life.”

After suggesting that these expectations might be innate, the authors then note that “it becomes particularly interesting to look at world leaders today and see whether or not they meet these expectations…”

So, how can I use this?

Dr. Baillargeon suggests that parents can use the findings to reframe their approach when trying to deal with their children’s bad behavior. Comparing the finding that infants grasp the concept of authority figures to our understanding that they grasp the idea of fairness, she explains that:

“Infants do not need to be taught that authority figures should be obeyed, but they may need to be helped to keep their self-interest in check so they respond to authority figures as they should. In other words, infants understand something about how authority figures should be treated, and about the obedience that is owed to them, and this is something that parents and caregivers can build on when interacting with children, by reminding them of what they already know.”

It seems like an understanding of the differences between leadership and bullying develop at a young age and that infants have certain expectations of how people should react to them. The findings support the idea that our minds are structured in a way that innately includes an understanding of authority. While questions of how far the findings of this study go remain open, the study gives us great insights into how our moral psychology develops.