We are spectacularly bad at predicting the future. Ignore the AI hype and fear

Prometheus brings fire to humanity (Credit: Heinrich Füger / Public domain / Wikimedia Commons)

- Throughout history, many expert predictions about technology have been spectacularly misguided.

- Today, forecasters say AI will either enslave or liberate us, but the history of prediction suggests we have little way of knowing who will be correct.

- Predictions are often disguised attempts to exert influence on others.

In 1934 Albert Einstein said, “There is not the slightest indication that nuclear energy will ever be obtainable.” Little more than a decade later, the U.S. dropped two nuclear bombs on Japan. Einstein, though mostly exceptional, was unexceptional in getting the future wrong.

A long history of bad predictions

History has preserved a catalog of bad predictions, especially when it comes to technology, and forecasts about AI soon will join these ranks in one of two categories: underestimation and overestimation.

American inventor and radio pioneer, Lee de Forest, offered an object lesson in underestimation when, in 1957, he said: “To place a man in a multi-stage rocket and project him into the controlling gravitational field of the Moon where the passengers can make scientific observations, perhaps land alive, and then return to earth… such a man-made voyage will never occur.” Just 12 years later, man walked on the Moon.

Hindsight also reveals that overestimation can be similarly misguided. Take this passage from a 1966 article in Time magazine, referring to a study by Rand, for example: “82 scientists agreed that a permanent lunar base will have been established long before AD 2000 and that men will have flown past Venus and landed on Mars.” Not quite.

Predicting AI

The internet is full of predictions about AI, but there’s no reason to believe we will have any more success with foreseeing its future than the litany of experts whose expectations for technology have already been exposed by hindsight.

Many of today’s claims about AI seem reasonable. But the problem is that every new technology inevitably exhausts itself at some point and ceases to develop in any fundamental way — and what is especially difficult is that we can never know what that limit will be or when it will arise. In 1909, Scientific American noted, “That the automobile has practically reached the limit of its development is suggested by the fact that during the past year no improvements of a radical nature have been introduced.”

The automobile soon replaced the horse and reshaped the world, but the hovercraft that some predicted would replace the automobile has not yet materialized, and although we foresaw flying cars — perhaps to appear at scale soon — there is no essential difference between driving in 2023 and in 1963. Perhaps AI will follow a similar trajectory, and much sooner than we think, despite how much it promises.

Then again, sometimes technology really does deliver, and sometimes it suddenly pushes beyond what seemed like a developmental limit. Maybe even the wildest predictions about AI are woeful underestimations. The point is that we have always been terrible at predicting the future and that our inability to do so is a strange but inescapable truth.

This is worth remembering as we get rather hot under the collar about AI. Some think it will liberate humanity. Others believe it will create religious cults and enslave us. Some think it will shake things up before settling into its place and that politics, love, war, and football shall proceed as they always have, if only in a slightly altered form. Others say it is a fad, and that what we see now is the zenith. Nobody actually knows. But we can console ourselves with the knowledge that nobody has ever really known anything about the future.

It is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future

Why are we so bad at guessing things to come? I suspect the world is an order of magnitude too complicated ever to accurately model. Unpredictable events guide great changes and you simply cannot predict the unpredictable. Think of Thomas Malthus, who could not have foreseen the Industrial Revolution when he predicted population collapse.

AI is leading somewhere, but whether it’s a dead end or a societal transformation we do not — and cannot — know. Ancient Greek historian Diodorus of Sicily may have put it best when he said, “What is strange is not that unexpected things happen, but that not everything which happens is unexpected.”

But why does any of this matter? So what if people make bad predictions about AI? Studying history’s endless catalog of bad predictions prepares us to be disappointed, surprised, or shocked by the future. “The most vivid teacher of the ability to bear the changes of fortune nobly is the recollection of the reversals of others.” Diodorus, once again.

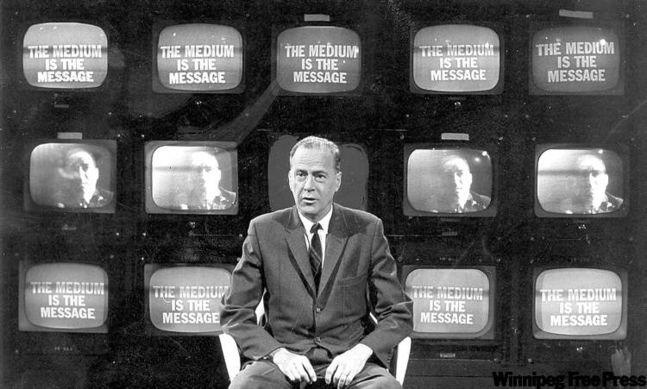

Predictions carry hidden motivations

More important about predictions than whether they are accurate or not is what they reveal about the people who made them. We should not be surprised that many who portended the failure of the automobile had a vested interest in horses. They wanted it to fail and feared its success. Karl Marx may have earnestly believed his own prediction of Communist revolution in Britain — he also wanted it to happen.

So when news outlets blare, “X is going to happen,” we should instead read, “We want X to happen.” Some people want AI to change the world and therefore say it shall; others are scared and say the opposite. Thus, we ought to ask of any prediction we come across: Who benefits if it comes true?

There’s yet another level to this. Predictions are mostly intended to direct our choices. Economists predict recession: Time to save. Or a boom: Time to spend. We are told climate catastrophe is imminent: We must change our ways. Or that this is untrue: Carry on as we were. So, coming from people we are supposed to trust, predictions have consequences regardless of how accurate or informed they are (and, as we have seen, rarely are they the former, even if supposedly the latter).

Call them prophets, clairvoyants, futurists, or experts, but one and the same, they have the power to terrify, excite, and manipulate. They hope to influence our decisions to suit their own ends. This is much why Tiberius banished soothsayers from Rome and why Dante placed them in the eighth circle of the Inferno, forever to be punished with their heads twisted monstrously backward.

Promethean desire

There is one more category of prediction that’s worth considering in the context of AI, in which somebody predicts not merely what will happen but what they intend to do. Ali proclaimed, “Archie Moore must fall in four,” and duly knocked him out in the fourth round. Petrarch predicted the end of the Dark Ages (a concept he invented, mind you), and without his work the Renaissance wouldn’t have happened. Filippo Brunelleschi predicted the return of Classical architecture and made sure of it by building the dome of Florence Cathedral. Norman Bel Geddes envisioned a world of highways, and his collaboration with General Motors at the 1939 New York World’s Fair helped make that vision a reality.

These are not people who prognosticated; they built the future they foresaw. Anybody can say we will have flying cars or establish a lunar base, but it is much harder to invent flying cars or take us to the Moon. Anybody can hold forth about what AI will or will not do. Rarer are those with the intention and means to bring such possibilities to life. These people we ought to take more seriously. We can compare them to the title character in Aeschylus’ play about the origins of human progress, Prometheus Bound, who explains: “What I foresee will come to pass — and it is also my desire.”