The other, more important Renaissance you never learned about

- Italy is considered the birthplace of the Renaissance, in part because of its Roman heritage.

- At the same time, significant artistic and scientific developments were taking place in Northern Europe.

- In many ways, these developments were more important than the ones happening further south.

In the mid-15th century, Pope Nicholas V was wading through the bowels of the Vatican archives when he stumbled across a dusty manuscript titled De Medicina, or On Medicine. It was written in the 1st century AD by Aulus Cornelius Celsus, the finest physician of the Roman Empire, and it contained chapters on the benefits of exercise and the treatment of pneumonia, among other topics. It was thought to have been lost centuries ago, and would have stayed lost were it not for the curiosity of the pope.

On Medicine is one of several ancient texts whose rediscovery facilitated the Renaissance. This movement, which lasted roughly from 1300 until 1600, is often discussed in relation to Italy — and for good reason, as many of those aforementioned texts ended up there through Roman conquest. Italy was also the home of many a Renaissance star, including Leonardo Da Vinci, Niccolo Machiavelli, and Michelangelo, whose contributions to humanity were funded by the fortunes that Italian merchants accrued along the Silk Road.

But while the Renaissance may have originated in Italy, it was by no means a uniquely Italian phenomenon. In his new book, The Other Renaissance: From Copernicus to Shakespeare: How the Renaissance in Northern Europe Transformed the World, Paul Strathern — philosophy lecturer at Kingston University and author also of The Medici and The Borgias: Power and Fortune — argues some of the most consequential events from this time period took place in northern Europe, often independently from what was happening down south.

Among these events, Strathern counts the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in Germany, the Protestant Reformation instigated by Martin Luther (also in Germany), and the heliocentric theory of Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, which holds that the Earth revolves around the Sun rather than the other way around. Additionally, several chapters from The Other Renaissance are devoted to acknowledging other, lesser known heroes from these regions, like Paracelsus.

Mysteries of putrefaction

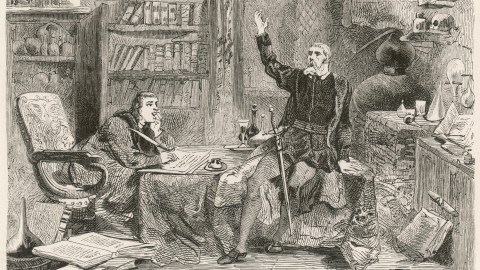

The Swiss physician Theophrastus von Hohenheim is not only remembered for his bold ideas but also his colorful personality. He wore alchemist robes, carried a large broadsword on his hip, and went by the name Paracelsus, meaning “greater than Celsus” (that is, the aforementioned physician from the Roman Empire). During his 1526 inaugural lecture as professor of medicine at the University of Basel, he surprised his class with a plate of human excrement, warning them that “if you will not hear the mysteries of putrefaction, you are unworthy of the name of physicians.”

Though often told for laughs, this anecdote highlights an important change in scientific thought. Paracelsus lived in a time when medicine was moving away from philosopher’s stones, zodiac alignments, and humors — the notion that disease is caused by an imbalance of blood, phlegm, and bile — toward something more empirical. By studying excrement, Strathern writes, Paracelsus hoped to understand “how the human body functioned, gaining its nourishment and expelling extraneous, often toxic, matter.”

Paracelsus was a rebel. Reading his namesake’s On Medicine (courtesy of the Vatican) led him to reject the academic orthodoxy of the Dark Ages. Instead of attending university, he traveled throughout Europe and Asia Minor collecting medical knowledge from societies that were politically and culturally isolated from one another. Back home, he used this knowledge to treat the Dutch philosopher Desiderius Erasmus, who up until then had been unable to find a cure for his mysterious ailments.

As a teacher, Paracelsus valued experience over instruction. “The patients are your textbook,” he said, “the sickbed is your study.” Like Luther, who translated the New Testament so Christians could read the text for themselves without interference from a preacher, Paracelsus delivered his lectures in German rather than the customary Latin so he, says Strathern, “would be understood by all the local barber-surgeons, alchemists, and itinerant quacks whom he publicly invited to hear him speak.”

Over the rainbow

More than two centuries before Paracelsus was born, a Dominican friar known as Dietrich (Theodoric) of Freiberg looked up at a rainbow and wondered what it was, where it came from, and why it only appeared in tandem with rain and sunlight. The explanation offered by his fellow friars — that rainbows were a literal gateway to heaven and a manifestation of God’s promise to Noah to never again conjure up another world-ending flood — did not satisfy him.

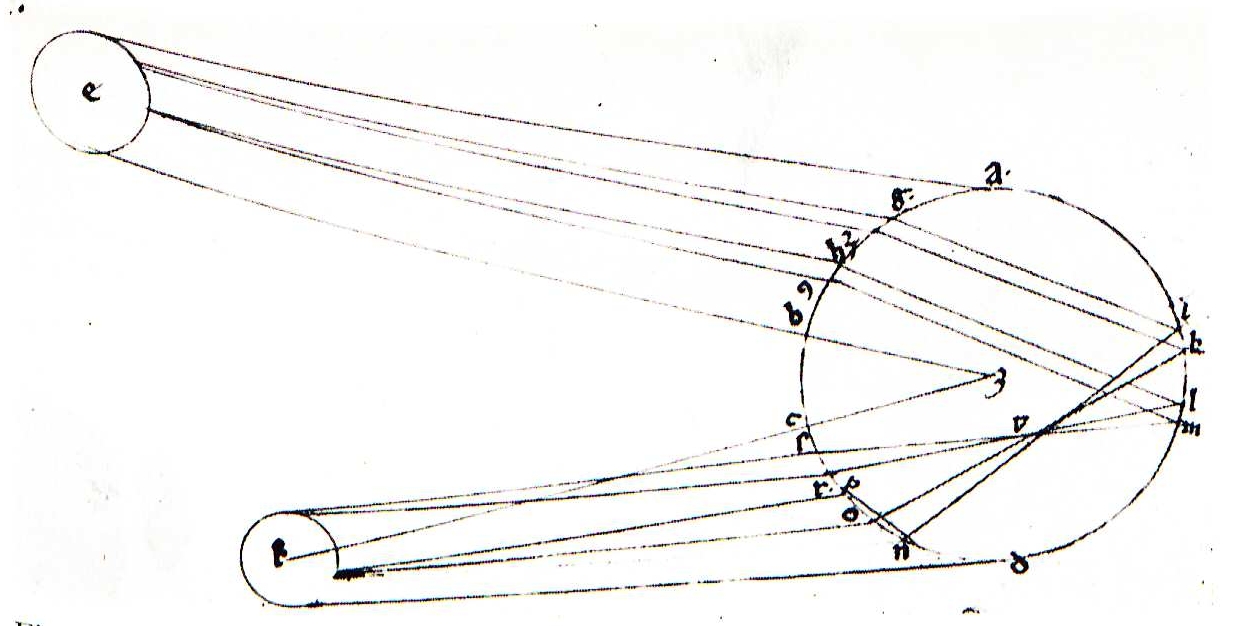

Dietrich sought answers not in the Bible, but a commentary on Euclid’s Optics written by the 10th century Arabic mathematician Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham. Al-Haytham agreed with the ancient Greek geometer’s proposition that sight was created by light, but where the latter thought our eyes emitted that light, the former believed they merely received it. Inspired by Al-Haytham, Dietrich wondered if rainbows could really just be nothing more than sunlight, refracted into different colors by raindrops.

Thinkers from previous generations might have written down their theory and called it a day, but Dietrich felt compelled to put it to the test. In lieu of an actual droplet, the friar filled a large round glass with water, held it up to the sun, and in so doing created his own miniature rainbow. Not only did Dietrich prove what rainbows were made of, but also why they lack a point of origin: Because they are made of refracted light, their approximate location changes depending on one’s point of view.

Strathern puts Dietrich’s discovery, which may seem small and insignificant compared to the feats of modern science, into perspective. “During this period,” he writes, “the whole idea of practical experimentation was for the most part confined to the dubious fume-filled realms of the alchemist’s den.” Knowledge was “confirmed by appeal to authority,” usually the Church, rather than verified through inquiry, giving rise to the very system Paracelsus would go on renounce.

Underappreciated art

Despite its relevance, much of the Northern European Renaissance’s artistic output languishes in the shadow of David and the Mona Lisa. The French writer François Rabelais combined the elegance of Greek literature with the obscenities he witnessed in countryside taverns. His Gargantua and Pantagruel series, about a duo of bawdy giants, includes all the “scandalous behavior of everyday life which had been missing from much of the respectable literature of the medieval era,” Strathern says.

Gargantua and Pantagruel reads like an early form of parody, namely, writing that criticizes and questions institutions and conventions rather than praising or accepting them. In the prologue, Rabelais dedicates himself to “illustrious drinkers” and “pockified blades.” In one story, the protagonists open an exclusive monastery where monks and nuns live side by side, eat their fill, and follow a philosophy that encourages them to do whatever they want, whenever they want.

Perhaps the most famous artist from the Northern Renaissance was Albrecht Dürer, who between trips to Venice returned to his hometown of Nuremberg (itself a prominent trade hub) to develop a style that was entirely his own. Where Italian painters chased an idealized concept of beauty, Dürer treated art primarily as a medium of self-expression. His greatest work is personal — a plot of vegetation or a portrait of his aging, world-weary mother. He was also a prolific printmaker.

Dürer helped steer northern artists in a different direction than their southern counterparts. Whereas the Southern Renaissance, Strathern writes, “remained devoid of Dürer’s influence, moving away from his all-but-transcendent realism into the distortions of mannerism and the ornamentation of the baroque,” Dürer foreshadowed the increasing popularity of printmaking, which in the North would be elevated to the same level as painting.