3 unsung heroes who helped society overcome division

(Photos: Wikimedia/Frederick M. Brown/Getty Images/U.S. Embassy Jerusalem/Flickr)

- History’s great men and women may enjoy name recognition, but everyday heroes can be anyone willing to talk.

- We profile three everyday heroes who helped society overcome adversity through civil discourse.

- Their stories validate John Stuart Mill’s belief that good things happen when you converse with people with whom you disagree.

If your history class was like ours, it focused on the great-man view of history. We learned of generals who stormed the battlefield for a decisive victory. We memorized the speeches of powerful leaders preaching lofty ideals. And we remembered great inventors who updated our world to v2.0.

But the great man theory of history misses the point: History’s course is charted by everyday people. A powerful leader may offer an era its rallying point, but true progress advances when ordinary people engage in civil discourse to change minds one person at a time.

Here are three people who helped others overcome entrenched, bigoted divisions. They didn’t win a war or make a speech before an audience of millions. They engaged in conversations that helped remind others of our common humanity.

Gordon Hirabayashi (left), Minoru Yasui (center), and Fred Korematsu (right). These three civil rights activists took their arguments against the internment of Japanese-Americans to the Supreme Court.

Minoru Yasui

A lawyer from Oregon, Minoru Yasui was an integral figure in the fight against the United States’ internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Yasui attempted to join the army but was rejected because of his race — despite having obtained the rank of second lieutenant through a Reserve Officer Training Corps program.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which allowed the military to set curfews, designate exclusion zones, and intern American citizens based on ancestry. The order focused mainly on Japanese Americans living on the West Coast, but German and Italian Americans also faced these discriminating policies.

Yasui immediately hatched a plan to test the order’s legality in the courts: He deliberately stayed out after curfew to be arrested. His case went all the way to the Supreme Court. In Yasui vs. United States, the justices determined the curfew and executive order were valid. Yasui was released from prison in 1943 with time already served and ushered to a Japanese internment camp, where he was held until 1944.

With his court case lost, you would think Yasui would have been defeated, but he wasn’t close to being finished. As he once said, “If we believe in America, if we believe in equality and democracy, if we believe in law and justice, then each of us, when we see or believe errors are being made, has an obligation to make every effort to correct them.”

After being released from the camp, he worked diligently for the remainder of his life toward redress of the inhumane treatment of Japanese Americans. As a senior leader of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), he called for reparations and a legislative guarantee that the constitutional violations put upon Japanese Americans during WWII would never happen again, to any American. His and others’ convictions were eventually overturned in the lower courts in 1986, the year of Yasui’s death, and the JACL’s redress campaign culminated in Congress passing the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which called for reparations and an official apology from the president.

President Obama posthumously presented Yasui with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015.

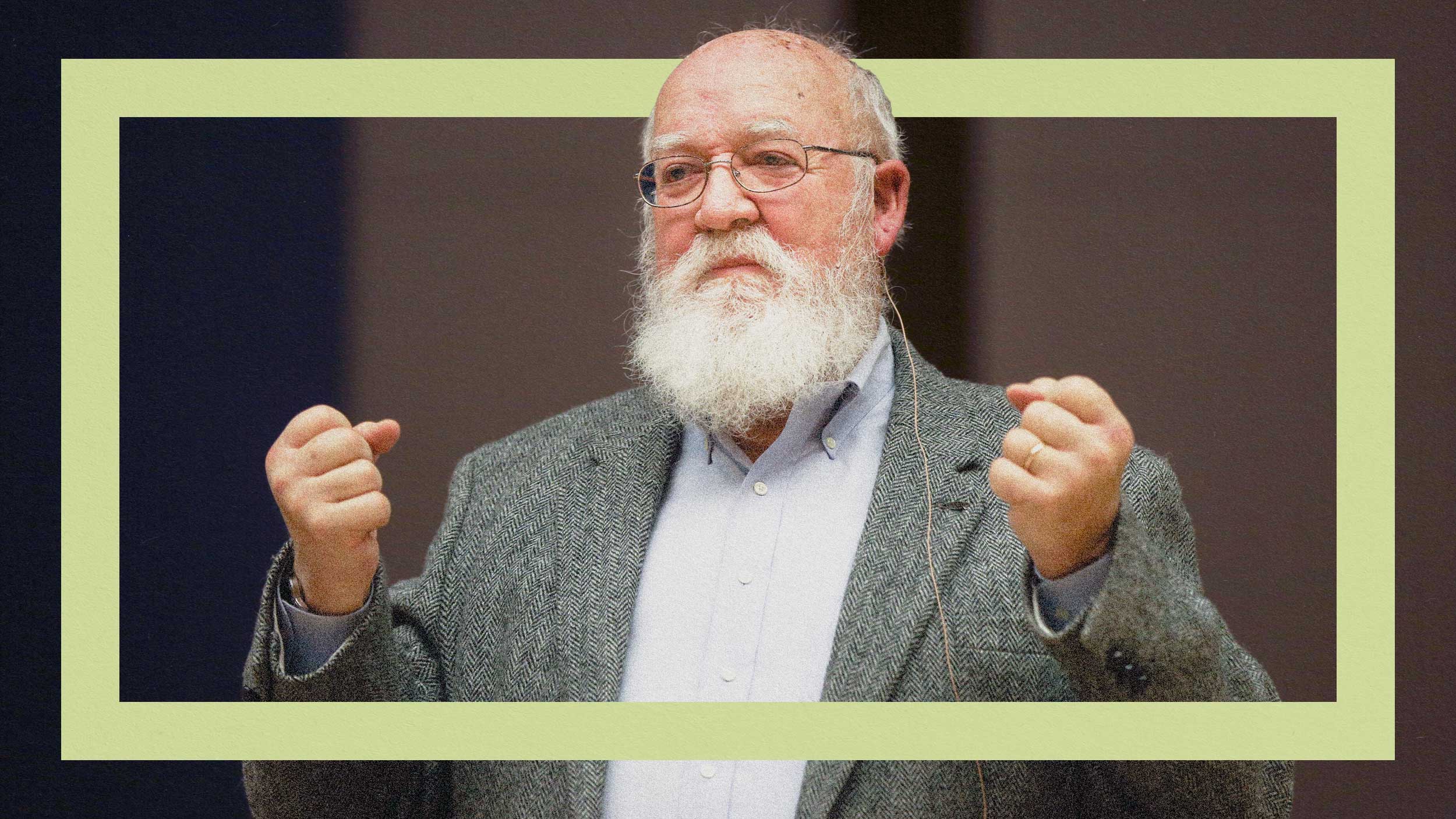

Daryl Davis shows a robe given to him by a Klansman who left the KKK. Davis keeps this and other robes he’s been given to remind himself that conversation can reduce hate in the world.

Daryl Davis

Daryl Davis is an R&B and blues musician. Nothing brings people together like great music, so Davis could have made this list on his virtuosity alone. But we’ve added him for another reason. As a black man, he made it his mission to befriend members of the Ku Klux Klan.

Davis met his first Klansman while playing piano at the Silver Dollar Lounge in Frederick, Maryland, more than three decades ago. The two struck up a conversation. The Klansman was surprised that a black man played in the same style as Jerry Lee Lewis. Davis informed him that Lewis’s musical idols were black musicians, a surprising revelation for the Klansman.

“The fact that a Klansman and black person could sit down at the same table and enjoy the same music, that was a seed planted,” Davis told NPR. “So, what do you do when you plant a seed? You nourish it. That was the impetus for me to write a book. I decided to go around the country and sit down with Klan leaders and Klan members to find out: How can you hate me when you don’t even know me?”

Over 30 years of conversations, Davis has convinced about 200 people to quit the Klan. When they leave, they give him their robes, which he keeps as a reminder that his efforts have measurably lessened racism in the world.

“Establish a dialogue,” Davis told the Daily Mail. “It’s when the talking stops that the ground becomes fertile for fighting. When two enemies are talking, they’re not fighting.”

How one black man convinced 200 KKK members to quit the Klan

Former Westboro Baptist Church member Megan Phelps-Roper has left the church and now advocates for the power of conversation.

Megan Phelps-Roper

Megan Phelps-Roper grew up in the Westboro Baptist Church. At the age of five, she began to picket with her family, hoisting up signs that read “God hates fags,” “Jews stole our land,” or “God sent the IEDs.” Later, she became the voice for the hate-filled organization on social media.

For most people this would be a nonstarter for any conversation, and for many, it was. Twitter responses directed at Phelps-Roper were typically filled with scorn and loathing. But through the noise, some conversations took shape. Phelps-Roper and a few of her detractors began to have open, civil conversations about their opposing beliefs.

“There was no confusion about our positions, but the line between friend and foe was becoming blurred,” she said during her TED talk. “We’d started to see each other as human beings, and it changed the way we spoke to one another.”

Thanks to her conversations with her cultural “enemies,” she left Westboro in 2012. Today, she speaks publicly on the power of conversations to overcome divisions.

“My friends on Twitter didn’t abandon their beliefs or their principles — only their scorn,” Phelps-Roper said. “They channeled their infinitely justifiable offense and came to me with pointed questions tempered with kindness and humor. They approached me as a human being, and that was more transformative than two full decades of outrage, disdain, and violence.”

The power of conversations

Of course, there are many unsung heroes whose quiet efforts have made this world a better, less divisive place, and we should celebrate them where we find them. As Sarah Ruger, Director of Free Speech Initiatives at the Charles Koch Institute, argues:

“How can we promote a culture of openness in society that makes us, as individuals, receptive to engaging with even the most deplorable views with the goal of changing them? At the end of the day I’m a John Stuart Mill nerd; I think nothing but good things happen when you engage with ideas with which you disagree. You either learn how to better defend your position, maybe you move closer to truth, maybe you persuade the other of a given view, but either way you’ve all learned something and been made better by that encounter.”

These three people show us the truth of John Stuart Mill’s belief. Engaging and debating with ideas we find wrongheaded or deplorable can not only help our society overcome division, but make us a stronger, more cohesive whole.