How four British migrations defined America

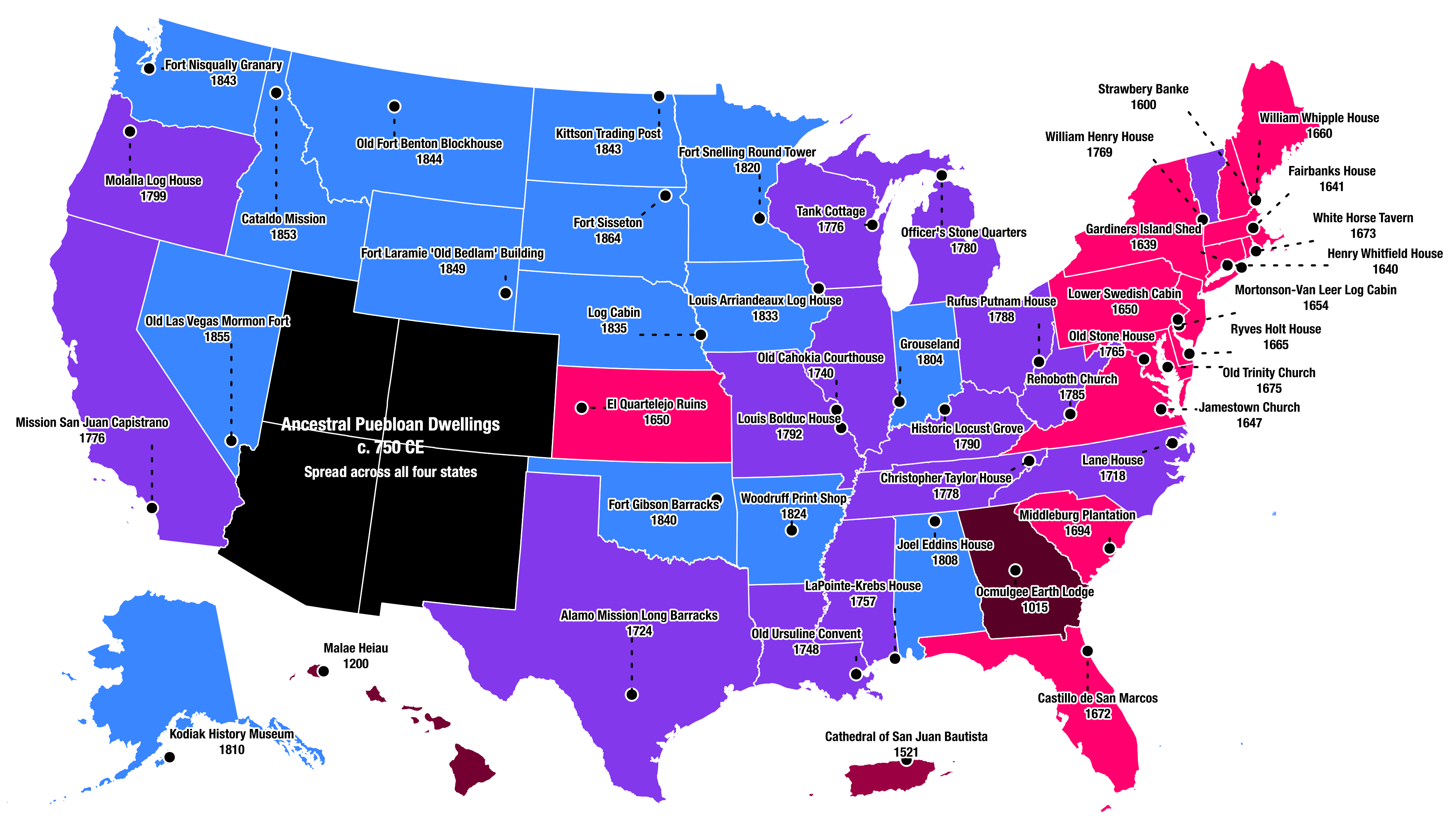

Credit: JayMan

- Early British settlement of the American colonies came in four distinct waves, from different places.

- Puritans, Cavaliers, Quakers, and Borderers had their own ideas of what America should be.

- Some of the cultural fault lines in today’s America can be traced back to those differences.

Quaker pioneer William Penn (center) treating with the Delaware Indians for the purchase of what was to become Pennsylvania.Image: Frieze by Constantino Brumidi (1865) in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol; via Architect of the Capitol – Public Domain.

How many Americans are of British descent? It’s a surprisingly difficult question to answer. Is that because, in an age of hyphenated identities, the founding one is still the default? Or has that identity become so amalgamated that it is now irrelevant? Perhaps the correct answer is: a bit of both.

In the 1980 Census, 61.3 million Americans (32 percent) self-reported British ancestry; most claimed English descent (26 percent), followed by Scottish (4 percent), and tiny amounts of Welsh (<1 percent) and Northern Irish. In the 2010 Census, that figure had dropped to 37.6 million (14 percent), with just 8 percent reporting English heritage, 3 percent Scottish and 2 percent Scotch-Irish.

The precipitous drop in self-reported British antecedents corresponds in part with the rise of those who identify as (unhyphenated) ‘American’, up from 12.4 million (5 percent) in the 1990 Census to 20.2 million in 2000 (7 percent) – the largest growth of any ethnic group in the 1990s.

However, back around the year 1700, about 80 percent of the population of what was to become the United States were of English (or Welsh) descent, with about 11 percent of African origin, and the rest being Dutch (4 percent), Scottish (3 percent) and other European. The imprint of the British on early American society was overwhelming, diverse and long-lasting: the regional and cultural differences between the settler groups created distinct regional and cultural identities in America.

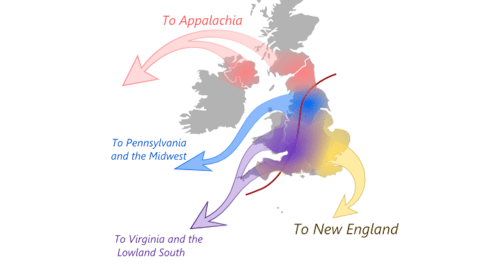

That’s the argument made by David Fischer, a history professor who in 1989 published a 900-page treatise on early migration to North America called “Albion’s Seed.” He identified four British ‘folkways’ that came over to the other side of the Atlantic in the 17th and 18th centuries (see map), each with their own ideas about the liberty they wanted to find there.

Map showing the origin and destination of four British ‘folkways’ that influenced American society.Credit: JayMan

1. The Exodus (1629-41)

- About 21,000 Puritans, migrating from East Anglia to New England.

- These religious fundamentalists believed in ‘ordered liberty’: everybody had the right to live by their own rules, and the duty to live according to God’s law.

- The Puritans were a major influence on the culture of the Northeastern U.S., especially in terms of business and education.

These religious fundamentalists are the ones who came over on the Mayflower and gave America Thanksgiving and the self-image of being a ‘City on a Hill’. Puritan society was gloomy and repressive: ‘exceeding the bounds of moderation’ was a punishable offense, and even just ‘wasting time’ got you into trouble.

The other side of the coin: life was very well-ordered. There was little income inequality and crime rates were low. Not only was charity towards poor the rule, being uncharitable was, yes, a punishable offense. Domestic abuse was punished severely. Women had a relatively high degree of equality. And government operated via town assemblies in which all could have a say.

2. Cavaliers and their Servants (1642-75)

- Some 45,000 Cavaliers drawn from English nobility and their indentured servants, migrating from the South of England to Virginia and the Lowland South.

- These aristocrats believed in ‘hegemonic liberty’: dominion over self, and others. In other words: keeping slaves was okay, but domination by others was not.

- The Cavaliers were the foundation of plantation culture in the South.

The Cavaliers came from the losing side of the Civil War in England, which was now led by the Puritan-inspired Oliver Cromwell. Royalist, Anglican, and aristocratic, they brought along with them their indentured servants – more than 75 percent of the total migration – hoping to recreate in Virginia and environs the socially stratified agrarian society they had left behind.

When their servants began dying en masse, they started importing African slaves, laying the groundwork for the race-based slavery system that underpinned the economy of the South until the end of the Civil War.

3. The Friends’ Migration (1675-1725)

- Around 23,000 Quakers, migrating from Northern England to the Delaware Valley in Pennsylvania, and later to the Midwest.

- These religious liberals believed in ‘reciprocal liberty’: granting others the freedoms they wanted for themselves, including the right to vote, to own, to be free, to worship, and to a fair trial.

- Quakers had an important impact on the industrial culture of the Mid-Atlantic and Midwestern regions of the U.S.

Halfway between the fun-hating Puritans and the pleb-hating Cavaliers, the Quakers seem modern and likeable. Believing everybody intrinsically good, they practiced tolerance, pacifism, gender equality, and racial harmony. They opposed slavery, the death penalty, and cruelty to animals and children.

Quakers replaced a wide range of social acknowledgements according to rank (bows, nods, grovels) by a single, neutral equivalent: the handshake. Quakerism was perhaps one of the first Christian denominations to become indistinguishable from liberal, secular modernity. On the other hand, they were even more prudish than the Puritans. Doctors had a hard time treating Quakers because they described everything from their necks to their waists as their ‘stomachs’, and everything below as their ‘ankles’.

4. The Flight from Northern Britain (1717-75)

- Some 250,000 ‘Borderers’, migrating from the Anglo-Scottish borderlands and Ulster to the Backcountry of Appalachia.

- These individualists believed in ‘natural liberty’: freedom to do as one pleases, without interference from society or government.

- Borderers contributed to the rural culture of America’s South and the ranch culture of its West.

Inhabiting the border regions between Scotland and England, and between protestant settlers and catholic natives in Ireland, the Borderers were used to violence and lawlessness, and to lives that were nasty, brutish and short.

It is no coincidence that they ended up in Appalachia, at that time itself a violent border region. It was the kind of world they knew. Borderers were wary of government, prone to violent family feuds, and not bothered by traditional morality. By one estimate, in the year 1767, 94 percent of all ‘backcountry’ brides were pregnant on their wedding day. These Borderers were not much beloved by other settler groups in America. One Pennsylvanian writer called them “the scum of two nations”. But the Borderers also contributed vigorously to the success of both the American Revolution and America’s westward expansion.

Representative Preston Brooks (SC) caning Senator Charles Sumner (MA) on the Senate floor. The attack, on 22 May 1856, symbolised the breakdown of civil discourse between North and South, prefiguring the Civil War. Credit: Lithograph by John L. Magee (1856); Public Domain.

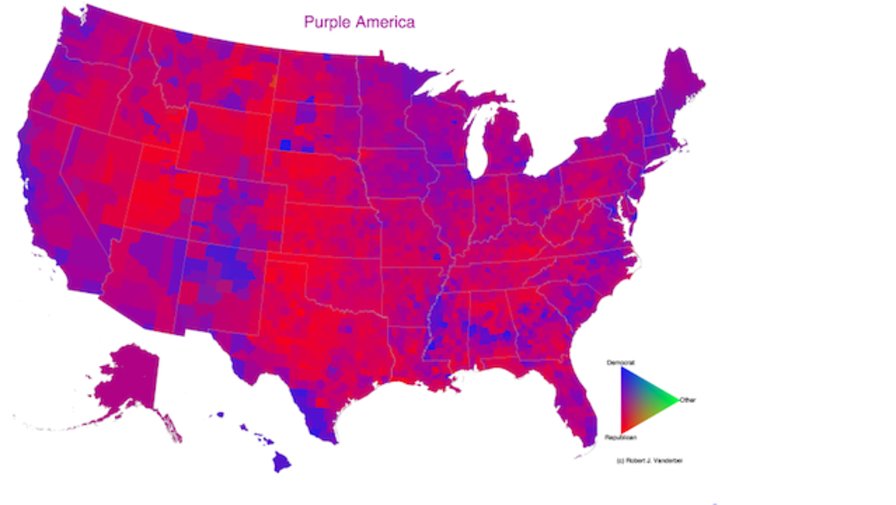

It’s tempting, and perhaps not entirely unjustified, to see in these four strains of British ‘folkways’ the antecedents of some of America’s current cultural divides. One might for example see Puritans and Quakers as constituting elements of the ‘blue’ tribe, while Borderers and Cavaliers could be considered the ancestors of the ‘red’ tribe.

But thinking of America as a “death match between Puritan-Quaker culture and Cavalier-Borderer culture”, as one commentator put it, is perhaps a bit too easy. There may be plenty of overlap within either pair, there is also much to distinguish each from the other. And then there are other and subsequent migrations contributing to and complicating the picture.

Nevertheless, a bit of cultural archaeology can be illuminating, if only to see where the bodies are buried.

Strange Maps #1049

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

Update 30 September: image reference for the map was changed to reflect the original source and producer of the map in question.