The history of America, by and for doctors

Credit: Boston Rare Maps

- We all know Columbus, but who remembers Diego Alvarez Chanca, his doctor?

- This map does – and it lists centuries of medical figures, events, and achievements.

- It provides an unusual perspective on North American history… with one exception.

The map illuminates the topography of America with simplified, symbolic representations of the persons, institutions and events that have shaped medical history.Credit: Boston Rare Maps

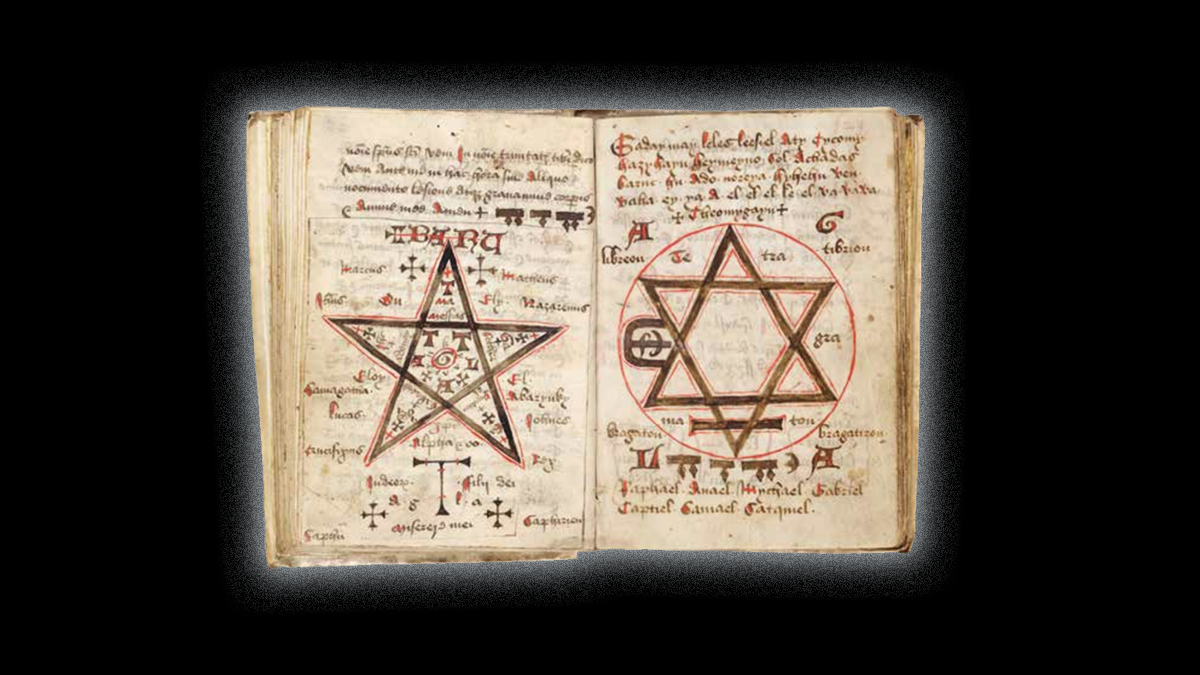

The map of America is a familiar canvas for a multitude of stories – soil types and weather fronts, road trips and election results. But sometimes geographical acquaintance intersects with narrative quaintness, especially when the topic is very specific. As in this beautifully detailed map of “Medical Events in North America,” as bizarre as it is instructive.

In the manner of a medieval miniature, it illuminates the topography of America with simplified, symbolic representations of the persons, institutions and events that have shaped medical history. That makes for some interesting discoveries.

For example, whatever our feelings about Columbus, we are familiar with him via his signature achievement. However, few will have heard of Dr. Diego Alvarez Chanca of Seville, physician to the king and queen of Spain, and here seen accompanying the intrepid and/or invidious Genovese on his second voyage to America (on the ship painted in the bottom right corner).

Dr. Philip Syng, holding up a jar with gallstones he removed from the bladder of Chief-Justice John Marshall, who contentedly observes from the operating table. Credit: Boston Rare Maps

While on Hispaniola in 1493, Chanca cured Columbus from an attack of malaria – quite probably the first application of western medicine in the western hemisphere.

For a good while, Spain remains the motor of medical progress in North America, with the publication in Mexico of “Opera Medicinalia,” the first medical book printed in the Americas (1570), and just 10 years later, the establishment of the first university chair of medicine in the New World, also in Mexico.

Circa 1760, Junipero Serra prevented and controlled an outbreak of scurvy in California with the use of citrus juice – doing so 34 years before the British Navy struck upon the same idea. The Spanish padre is shown holding up oversized slices of oranges, dripping with healing sap.

Soon thereafter, the initiative–medical and otherwise–is seized by the Anglos on the East Coast.

Dr. Samuel Gross, carting in cadavers for anatomical study. Credit: Boston Rare Maps

Many of the achievements detailed on this map were truly revolutionary, helping to elevate the state of medical science to the heights it has reached today. But, as the legend of the map says, “(t)he names of the prime-movers of science disappear gradually in a general fusion, and the more a science advances, the more impersonal and detached it becomes.”

So it’s nice to see remembered here, among other pioneers:

- Dr. Howard Taylor Ricketts (1871-1910), from near Missoula, who demonstrated the tick-transmission of Rocky Mountain spotted fever and died of Mexican typhus during the investigation and demonstration of the disease.

- Dr. J.C. Otto (1774-1844), from Philadelphia, who established haemophilia as a clinical entity.

- Sir Frederick Banting, working at Toronto University Medical School, who assisted by Charles Best managed to isolate insulin and succeeded in manufacturing it in 1922. Together with J.R.R. MacLeod, he received the Nobel Prize in 1923.

First called “Letheon”‘, ether was discovered by dentist W.T.G. Morton, and first surgically used at Massachusetts General Hospital. Credit: Boston Rare Maps

Several institutions are singled out as beacons of medical progress, notably

- hospitals like Massachusetts General Hospital, Johns Hopkins Hospital, the Mayo Clinic;

- educational centers of excellence such as Harvard Medical School, the Transylvania University Medical School and Jefferson Medical College; and

- associations such as the State Boards of Health (first one established in 1869 in Massachusetts) and the American Medical Association (founded in Chicago).

Among the achievements mentioned on the map with resonance for our own pandemic times are the Quarantine Enforcement Act, passed by Congress as early as 1799, and the stamping out, in 1905 in New Orleans of an “epidemic of yellow fever (…) by U.S. Public Health Service.”Produced in 1950 and reflecting on earlier times, the map is dominated by white males.

The exceptions proving the rule are

- Dr. Hideyo Noguchi (1876-1928), who was associated with the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research and who in 1911 discovered the agent of syphilis as the cause of progressive paralytic disease;

- Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910), the first woman in America to receive the degree of doctor in medicine, who together with Marie Zakrzewska established the first training school for nurses in America; and

- a procession of slaves owned by Washington and Jefferson, standing in line to get inoculated for smallpox.

Slaves of Washington and Jefferson, getting inoculated for smallpox. Credit: Boston Rare Maps

Few of the events and achievement mentioned on this map have made it into general public knowledge, with two possible exceptions.

One is “the American Crowbar Case”, an ‘extraordinary medical incident’ mentioned in a note stuck to the East Coast: “In 1848, an explosion propelled a 3 ½ ft. crowbar through the head of Phineas T. Gage and up into the air. The patient recovered completely except for loss of sight in one eye…”

The other, the curious case contained within Dr. William Beaumont’s book, “Experiments & Observations of Gastric Juices.” On June 6, 1822, a man named Alexis St. Martin was accidentally wounded by gunshot at Fort Mackinac. The wound healed, leaving a gastric fistula, through which Dr. Beaumont was able to make observations. But Mr. St. Martin “is a difficult subject (and) runs away repeatedly.”

Dr. Beaumont’s book on gastric juices, with pages illustrating the story of his unwilling subject, Alexis St. Martin. Credit: Boston Rare Maps

Really? Who doesn’t want a doctor poking into their stomach through a hole in their belly? But eventually the situation is resolved to the satisfaction of both parties: “Beaumont gets (Mr. St. Martin) commissioned as sergeant to keep him during experiments.”

One of the more familiar names on the map is that of Dr. Walter Reed, but mainly because he is now synonymous for the Army Medical Center named after him. The map reveals why he became famous enough for that honor:

In Cuba, Dr. Walter Reed (1851-1902) proved, together with Dr. Jesse W. Lazear, Dr. James Carroll and Dr. Aristide Agramonte, that mosquitoes were the carrier of yellow fever. Dr. Lazear & Dr. Carroll allowed themselves to be bitten by infected mosquitoes. Lazear died of the fever, Carroll’s health was permanently impaired.

Dr. Walter Reed (in white), in between Dr. Carlos Finlay (who first theorised that mosquitoes carried yellow fever) and Drs. Lazar and Carroll, who put that theory to the test. Credit: Boston Rare Maps

Although they are scant remembered today, their selfless sacrifice has doubtlessly saved the lives of many in the 120 years since.

Map produced in 1950 by Abbott Laboratories, a pharmaceutical company. A copy was recently sold by Boston Rare Maps. Image kindly provided by Mike Buehler at Boston Rare Maps.

Strange Maps #1059

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

Dr. Theobald Smith established that tick bits caused Texas Fever in cattle, thus proving that insects can carry diseases. Credit: Boston Rare Maps