Why do ‘Kevins’ vote for far-right parties?

Credit: Guillaume Durocher

- Kevin (1), Cindy and other ‘Anglo’ first names are especially popular in some areas of France and Germany.

- These also happen to be the regions where far-right parties are very successful.

- The link: working-class whites, inspired by English-language pop culture and disaffected from mainstream politics.

Demonstration in Paris against French president Macron, by the so-called ‘Gilets Jaunes’ (‘Yellow Vests’). According to a prominent French pollster, the fact that many of these have ‘Anglo-Saxon’ first names is sociologically relevant. Credit: Stéphane de Sakutin/AFP via Getty Images

We need to talk about Kevin. No, this is not about that book. This is about why areas of Germany and France with a lot of Kevins (and Justins, and other so-called ‘Anglo-Saxon’ first names, for that matter), tend to vote for extremist right-wing parties.

Take the two maps below. The one on the left shows where in Germany ‘Kevin’ is a popular first name. Quite clearly, Kevin is more prevalent in the former east, and especially so in Saxony, the southern state of the former GDR.

The map on the right shows the results of the so-called Zweitstimme (‘second votes’, or party list votes) in the German parliamentary elections of September 24, 2017. The right-wing Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) obtains its best score in Saxony, a.k.a. Kevin Country: 27 percent, more than double its national average (12.6 percent).

One caveat: the map on the left shows the popularity of the name Kevin for new-borns since 2006 – those kids were at most 11 years old at the time of the election on the other map. So it’s not Kevins voting for AfD, but their parents.

In Germany, Kevin Country (left) is also far-right AfD territory (right).Credit: Doyen Mandelbrot

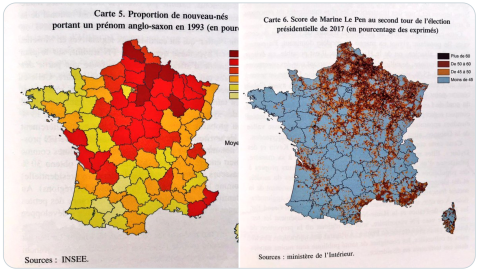

Or take the next map pair. The one on the left shows French newborns in 1993 with an ‘Anglo-Saxon’ name. The highest share of Ambers, Dwaynes, and other newborn ‘Anglos’ are found in areas colored various shades of red: light (13 percent), medium (14 percent), or dark (15 percent and up). Those areas are predominantly in the north and centre of the country – but excluding Paris and environs.

And now take a look at the map on the right, showing the results of Marine Le Pen at the second round of the 2017 presidential elections, held on May 7. The winner was Emmanuel Macron (66 percent), but Le Pen, candidate for the far-right National Front (2) obtained just shy of 34 percent of the overall vote.

Ms Le Pen obtained her highest scores, up to 60 percent of the total, mainly in the north of the country, in a zone largely contiguous with the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ one on the other map – both zones perforated by a non-compliant Paris.

According to Jerôme Fourquet, these twin phenomena are an indication of the ‘archipelisation’ of French culture.Credit: Guillaume Durocher

In L’ Archipel français, Jerôme Fourquet, an executive at IFOP, the famed polling institute, provides some background to the correlation. His sociological portrait of France paints a picture of three related evolutions: the obliteration of the traditional left-right divide in society, the ‘archipelisation’ of French culture into diverging subcultures, and the deepening alienation of working-class whites from the political mainstream.

Fourquet charts social changes by analysing the first names in French birth registries. Take for example the fate of Marie: its decline as the name of 20 percent of newborn girls in 1900 to no more than 2 percent since the 1970s marks the retreat of conservative Catholicism. In wartime, patriotic first names like France or Jeanne (i.e. Joan of Arc) see their fortunes rise.

One of the most remarkable trends in recent decades is the rise of ‘Anglo’ first names, from a mere 0.5 percent in the 1960s to 12 percent in 1993 – many of those names are taken from the music and movie stars of English-language pop culture. The phenomenon is mainly restricted to the lower classes. France’s metropolitan elites wouldn’t dream of naming their offspring Kevin or Justin, Cindy or Britney.

Fourquet notes the prevalence of ‘Anglo’ first names among the gilets jaunes, the yellow vest-clad protest movement that plagued Macron during his first years in office.

It is from the same source of disaffected lower-class whites that Le Pen draws most of her support, the pollster argues. Hence the overlap between France’s ‘Anglo’ zones and the Le Pen-voting parts of the country – evidence of the ‘archipelisation’ of French society.

It can be argued that a similar conjuncture between identification with English-language pop culture and disaffection with mainstream politics is at work in Germany.

Maps found here and here on the twitter accounts of Doyen Mandelbrot and Guillaume Durocher. Many thanks to Renke Brausse for pointing them out.

Strange Maps #1067

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

(1) ‘Kevin’ is in fact a name of Irish origin – it is the anglicised form of ‘caoimhín’, which means ‘of noble birth’. However, from the perspective of non-Anglophone cultures, it is an ‘English’ name.

(2) The Front National has since been renamed Rassemblement National, or ‘National Rally’.