The Crying Game

Whenever I hear the name of Turner Prize-winning artist, Chris Ofili, I unfortunately think of the old Monty Python joke: “What’s brown and sounds like a bell? Dung!” For Americans who still remember Rudy Giuliani’s dung-inspired demagoguery in the mid-1990s, Ofili remains defined by that single word and single, controversial moment. A new exhibition at the Tate Britain and a revelatory new book, however, look to redefine this anger- and thought-provoking artist.

In 1996, as part of a group exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum titled Sensation, Ofili’s painting The Holy Virgin Mary raised the ire of then-New York City mayor Giuliani, who cried blasphemy at the elephant dung lacquered, painted, and included in the work. (Giuliani apparently didn’t look closely enough to notice the tiny photographs of female genitalia Ofili had pasted all over the painting. Or at least he never mentioned them.) Giuliani “seized control of the event, set the terms in the public arena, and constructed the painting’s meaning from his own ignorance,” Carol Becker writes of the incident in the monograph. The art world worked overtime “to get the media to recontextualize, redefine, redescribe, and reinscribe it with the meaning the artist had intended.” The battle, even 14 years later, wages on in Ofili’s work between artistic intent and public reception. The fact that the debate continues attests to the value of Ofili’s work in modern art and, however silently, modern, multinational, multiethnic culture.

“I don’t think religion is a springboard for spiritual enlightenment,” Ofili confesses in an interview that closes the monograph, perhaps thinking of The Holy Virgin Mary’s effect. “I don’t think it necessarily takes you to a greater place, but it can put you in the mood.” Likewise, Ofili’s works may not take you to a “greater” place, but at least they leave you in a pensive mood, wondering what they mean and what they should mean to us. Becker describes Ofili’s approach as “the mercurial imagination—a type of creativity that can’t resist sullying what has become oppressively sanctified, pure, and at times hidden and inaccessible.” Ofili pulls our idols off their pedestals, dirties their faces, and hands them to us—more human and more immediate than before. It’s a dirty game, but Ofili demonstrates how necessary it is to play. The Giulianis of the world may refuse to look, but most of us cannot afford that luxury if we aim to survive with one another.

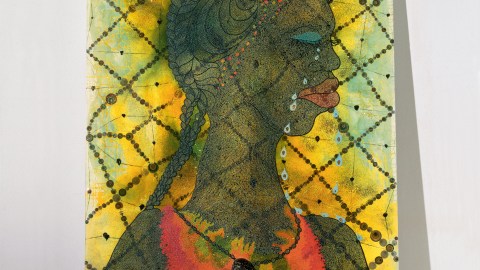

Ofili’s 1998 painting No Woman, No Cry (pictured) stands as just one example of the artist sullying on the surface what is already sullied within. Borrowing the title of Bob Marley’s reggae hit, Ofili dedicated the work to the mother of London teenager Stephen Lawrence, whose racially motivated murder revealed the racist underside of the London police force that tried to cover it up. Tiny photos of Lawrence make up the tears that fall from the woman’s face as the title appears in colored pins inserted into balls of dung at the foot of the painting. In an image both specific and universal, Ofili plays with multiple meanings to show us the face of racism as well as its consequences.

It is this “deep historical ambivalence” of Ofili over the alleged progress made in human rights, Okwui Enwezor writes in his essay, that led Ofili to challenge the nationalist tradition when representing Britain at the 50th Venice Biennale. With the work titled Within Reach, Ofili “began from the point of dismantling and remaking imperial British memory as well as enumerating its postcolonial history,” Enwezor writes, “so as to shift its horizon and bend it towards the line of a transnational African and disporic imagination.” Whether a single teenager killed just yesterday or the holocaust of the African slave diaspora centuries ago, Ofili shifts our imagination to a different level to reveal the evils without as well as those that, perhaps unconsciously, lurk within us.

“The process of making art is like crafting a key that can open a door to freedom,” Ofili argues in his interview. Together, this exhibition and this monograph offer a key to unlocking the potential for contemplation within Ofili’s art as well as for freeing ourselves from the bonds of racism we many of us cannot admit still hold us.

[Image: Chris Ofili, No Woman, No Cry (1998). Acrylic, oil, polyester resin, pencil, paper collage, glitter, map pins and elephant dung on linen. 243.8 x 182.8 cm. Photo: Tate. © Chris Ofili.]

[Many thanks to the Tate Britain for providing me with the image above from the exhibition Chris Ofili, which runs from January 27 through May 16, 2010, and to Rizzoli for providing me with a review copy of the first monograph on the artist, Chris Ofili.]