CSI: Renaissance Italy

Who killed Caravaggio? Or what killed Caravaggio? Four hundred years later, who cares? To “celebrate” the 400th anniversary of the demise of the demented genius of the Renaissance, Italy’s National Committee for Cultural Heritage looks to answer these questions once and for all. According to a report from Reuters, a team from the departments of Anthropology and Cultural Heritage Conservation at the universities of Ravenna and Bologna will play a different kind of tomb raiders in search of Caravaggio’s remains. The process, however, which sounds more convoluted than an episode of CSI, would challenge even Gus Grissom’s team.

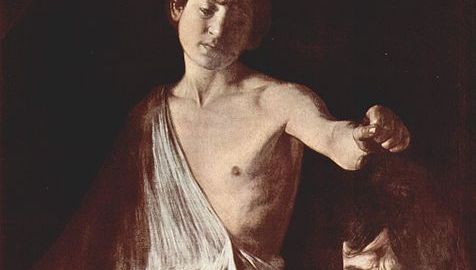

Thanks to the discovery of a slip of paper left in a book four centuries ago, scholars now believe that Caravaggio died in a hospital of some disease, either typhus or malaria, rather than violently at the hand of an assassin paid by one of the artist’s many enemies. Assuming that that paper is true, the experts expect that Caravaggio’s body was laid to rest in a nearby cemetery. The thirty bodies in that cemetery were moved in 1956 to another cite. All the team of anthropologists need to do is examine those thirty skulls, create computer models for each one to determine what the original owner may have looked like, and then compare those models against the self-portraits that Caravaggio painted in such works as David with the Head of Goliath (pictured), in which the artist gave himself the role of the fallen Philistine. Simple, right?

Even if this team succeeds in their mission, and I wish them well, part of me wonders what we’ll gain by knowing how Caravaggio met his maker. Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio so lived by the sword that dying by it seems poetic justice. Even if you buy the death by disease possibility, I much prefer Simon Schama’s recreation in his Power of Art series, in which a wild-eyed, sweat-covered Caravaggio slumps to the sand as he walks along the surf towards Rome, where a cardinal awaited to grant him the pardon that would restore Caravaggio to the good graces of the rich and powerful in the Roman church. David with the Head of Goliath traveled separately to Rome—a peace offering to the cardinal. On David’s sword reads Humilitas occidit superbiam, Latin for “Humility kills pride.” Whether the prideful genius could ever achieve humility is as much a mystery as the circumstances of his death. Schama milks the arrival of the humble peace offering minus the painter as the final stroke of a tragic existence.

Caravaggio died childless. The scientists will resort to analyzing the DNA of the artist’s closest blood descendents in search of a match. In terms of art, Caravaggio left many “children”—the Caravaggisti that spread the gospel of chiaroscuro-drenched psychological realism across Europe. Many artists copied Caravaggio’s style second and third hand, never knowing the original, eventually diluting the emotional power of deep contrast into an elaborate parlor trick. In fact, Caravaggio’s name nearly disappeared from the ranks of great artists until the early twentieth century, when art historians rediscovered him. Caravaggio’s “near death” experience in the great chain of artistic genius strikes me as more fascinating than his physical death. Perhaps a better celebration of Caravaggio’s shuffling off of this mortal coil would be a exhumation of the circumstances that made him the great artist he was while simultaneously the self-destructive cautionary tale of legend.