What Ruling Against Stalin’s Grandson Says About Russia

In a vindication of sorts for Stalin’s victims – as many as 20 million – a Moscow district court last week ruled against the dictator’s grandson, who sued a Russian newspaper for calling him a “bloodthirsty criminal.” But the verdict, while a welcome sign, does not undo the disturbing fact that many Russians’ still give the Soviet leader high approval ratings. Nor does it reverse efforts by the Kremlin to rehabilitate one of the twentieth century’s most ruthless leaders.

In a July 2006 speech, then-President Vladimir Putin told Russians they “shouldn’t feel guilty” about Stalin’s purges. He also accused Western academics of downplaying Moscow’s role in ending World War II and exaggerating the atrocities committed by Stalin. Putin had previously made waves by calling the collapse of the Soviet Union the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the twentieth century” and reinstating the Soviet national anthem.

The Kremlin, some experts say, has sought to polish up its Soviet past in an effort to reassert itself on the world stage and restore national pride among Russians. Unlike post-apartheid South Africa or post-Nazi Germany, Russia has never fully come to terms with the darker chapters of its past or ever established a truth commission to investigate Soviet-era atrocities. Some say neo-Stalinist attitudes are partly responsible for Russia’s tougher posture toward countries like Ukraine and Georgia, as well as for its prickly dealings with the United States.

During the Bush years, the Kremlin’s attempts to gloss over Soviet history dovetailed with rising anti-Western attitudes among Russians. “There is a steady drip, drip, drip coming from the Kremlin and on Russian television that is intensely anti-American,” says Sarah E. Mendelson of the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “[Russians] increasingly view the United States as more of a threat than China or Iran. Plus, there is this rejection of seeing Russia as part of the Euro-Atlantic community.” The Bush-era plan to place a missile defense system in Central Europe and open NATO’s door to Ukraine and Georgia corresponded with a spike in Russian nationalism and anti-Western rhetoric. Yet with the new administration in Washington promising to “reset relations” and put the kibosh on the missile shield, the inflammatory rhetoric has softened some, while Stalin seems to receive fewer shout-outs from the Kremlin these days.

But there has still been no full-scale investigation of Stalin-era atrocities. A few inquiries of past purges were launched by Mikhail Gorbachev during the late 1980s, and monuments to gulag victims were erected. “The high point of official truth telling was under Gorbachev,” says Stephen Cohen of New York University. “He believed the [gulag] system needed dismantling and he had to discredit the era in which the system was created. Gorbachev and [Politburo member and Kremlin adviser] Alexander Yakovlev had a very profound moral allergy to Stalinism.” Both of Gorbachev’s grandparents were deported by Stalin to Siberian labor camps. His denunciation of the system echoed Nikita Khrushchev’s famous 1956 secret speech in which he spoke out against Stalinism, which ushered in an era of de-Stalinization. But Gorbachev’s attempt to denounce Stalin did not go far enough. Marshall Goldman of Harvard University says he is surprised a more serious effort to prosecute crimes from that era was not made. “How can you come back from a camp and live next door to the person who sent you to the camp?” he asks. “That mystifies me.”

After Gorbachev exited the political stage, Boris Yeltsin picked up on his predecessor’s efforts to investigate past atrocities and rehabilitate victims. The KGB, Russia’s state security agency, was dismantled (or rather folded into the FSB). Archives were opened—albeit partially—and a series of trials were held. But as Richard Pipes, an historian at Harvard who attended the trials and provided expert testimony, told me a few years ago, “Nothing happened. No one was arrested or tried.” There were sporadic, mostly bottom-up efforts to create a truth commission to investigate Soviet atrocities, in addition to the work of Russian human rights groups like Memorial, but nothing of substance materialized. “It‘s a very difficult thing to repudiate seventy years of Russian history,” says Pipes. “They did this in Germany and Japan but we were the occupying power then.”

Some sites of former gulags have been preserved or made into museums and Russia has erected a few memorials to the victims of Stalin’s purges, including a statue erected in Moscow’s Lubyanka Square, but Pipes says “it’s a pitiful thing” that pales in size to a similar statue in Washington, DC. “The whole idea of having a monument to victims of communism is something that makes people [in Russia] mad,” says Stephen Sestanovich of the Council on Foreign Relations. “They don’t see it as a principle of national reconciliation.”

To be fair, countries are often cautious about rewriting their histories, and Russia is no different. “Millions of Russians simply aren’t going to spit on the biographies of their grandfathers or fathers any more than we are going to condemn the Founding Fathers because they owned slaves,” says Cohen. “They are not going to throw out the entire Soviet experience nor should they, because tens of millions of decent human beings lived their lives, married, and died with nothing but virtue on their minds. It’s not their fault what their government did or didn’t do.”

Others says this unwillingness to revisit past crimes may reflect Russians’ “inferiority complex,” something exacerbated by the economic stagnation and political anarchy of the 1990s. Many Russians blamed these growing pains on the policies of Western advisers bent on reducing Russia’s stature in the world. “Russians felt very bad they were no longer a superpower,” Goldman says. “They’ve always been a bit defensive and want to protect their image. Any attempt to undermine it is almost viewed as a form of treachery or self-hate.” Or as Cohen puts it: “The reaction to the 1990s was coming, and his name was Putin.”

Under Putin’s watch, nostalgia for Stalin has grown, even among young Russians. Majorities of young Russians now view Stalin as a “wise leader” and there appears to be no taboo surrounding the Soviet dictator, according to a 2007 report by CSIS’s Mendelson and University of Wisconsin professor Ted Gerber. They found a majority of young Russian respondents believed Stalin did “more good than bad.” Other polls show younger generations view Stalin, falsely, as the mastermind behind the Soviet Union’s victory over Nazi Germany in what Russians call the Great Patriotic War. In fact, historians say, Stalin had purged his officer corps, signed a secret deal with Hitler, and was caught unprepared by the advancing German armies. About 40 percent of young Russians believe that Stalin’s role in the repressions, too, was exaggerated, which Mendelson says affects their attitudes toward the current regime. “As long as Russians remain uneducated or mildly supportive, or even just ambivalent about a dictator who institutionalized terror, disappearances, slavery, and had millions killed, they are simply unlikely to protest disappearances in parts of Russia today,” she says. Large majorities of young Russians sympathize with Putin’s calling the collapse of the Soviet Union the twentieth century’s “greatest geopolitical catastrophe.”

Putin’s efforts to rehabilitate Stalin may be an attempt to shore up his own legacy. “In some ways, the legitimacy of Putinism does seem to rest on saying [the Soviet era] wasn’t as bad as people say,” says Sestanovich. “Why it’s not more legitimate to say ‘Let’s find out how bad it was,’ that’s something you’d have to ask [the Russians].”

Russians’ neo-Stalinism manifests itself in other ways as well. The opening in 2006 of a museum devoted to Stalin in Volgograd, once known as Stalingrad, provoked only a minor outcry from victims’ relatives. There has been a boost in enrollment among nationalist youth movements like Nashi (Ours), whose mission statements are eerily reminiscent of the Soviet-era Komsomol, the youth wing of the Communist party. Neo-Stalinism also affects Russia’s policies toward its neighbors. Its August 2008 war in Georgia or earlier feud with Estonia over the removal of a Red Army war memorial from its capital, for instance, were rooted in the Stalin-era policies of the past. “No doubt, when Russians react to the Baltic States and NATO their reaction is part traditional geopolitics, part national pride, and part neo-Stalinism,” says Sestanovich. Interestingly, according to the survey by Mendelson and Gerber, just 10 percent of young Russians think Russia should apologize for the Baltic occupation.

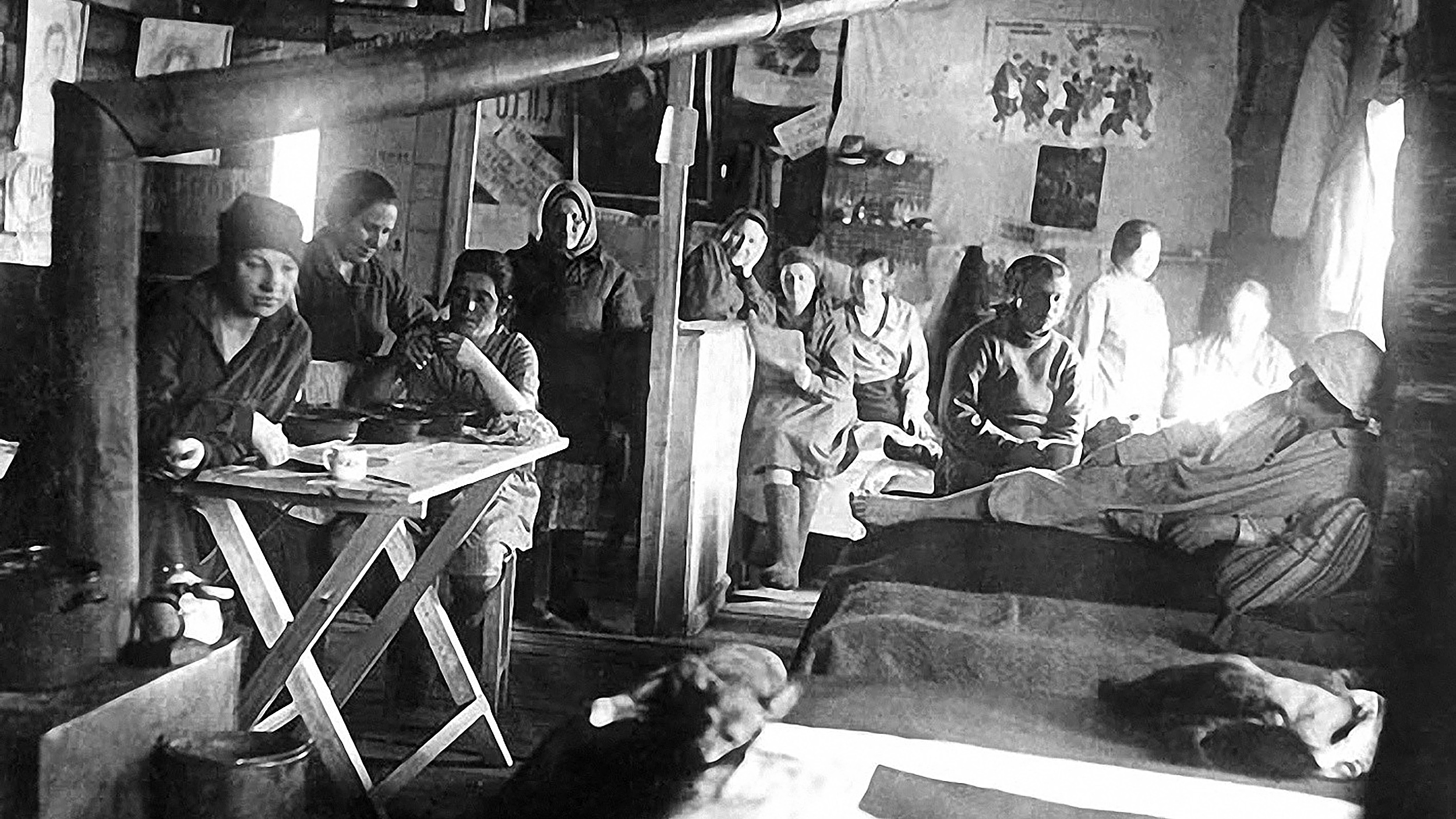

There is also the notion that Stalin’s “Great Terror,” which killed at least twenty million victims, never resonated broadly with the public outside of Russia quite like the Holocaust did. “To many people, the crimes of Stalin do not inspire the same visceral reaction as do the crimes of Hitler,” writes journalist Anne Applebaum in her book Gulag: A History. That is partly because of the comparative lack of archival research on Stalin’s purges—experts say access to archives has been tightened in recent years—and restricted access to labor camps, says Applebaum. Plus, unlike the Nazis, the Soviets did not videotape their gulags or victims. “No images, in turn, meant less understanding,” she writes. Hence, icons from the Soviet era like Lenin busts or hammer-and-sickle banners are now kitsch for Western tourists and sold at duty-free shops.

It’s unclear what effect a reopening—whether in the form of a South Africa-style truth commission—of Russia’s Stalinist past would have on its national psyche. In some ways, many Russians are already aware of Stalin’s purges from authors like Alexander Solzhenitsyn. “Of course, many of them know it,” says Pipes. “But others don’t want to know it.” He says it would be very upsetting for Russians to know the true extent of Stalin’s crimes. “The thing that makes Russians feel great is the Soviet Union in [outer] space, or its defeat of Nazi Germany.” Anything that debunks that era’s legacy, he says, would “have a terrible effect on them.” But others say an investigation of Soviet-era crimes would provide Russians with a catharsis of sorts and energize them to engage more in political life. “How a country, any country, reconciles with its past, especially with episodes of gross human rights violations, shapes political and social development,” says Mendelson.

While the recent court ruling against Stalin’s grandson signifies a small yet positive step against those seeking to rehabilitate the Soviet dictator and downplay his past crimes, Russia may still not be ready to have a full airing of that era’s atrocities. “Many people who worked for Stalin and [Leonid] Brezhnev are still alive,” says Pipes. “They don’t want to have this discussion. Maybe in ten or twenty years they will.”