Europe’s dry rivers reveal creepy “hunger stones”

- Water levels are at record lows in rivers across Central Europe.

- They’re revealing so-called “hunger stones” in German and Czech rivers.

- While they no longer prefigure famine, they do signal long-term climate change.

If you’ve recently dumped a dead body in a reservoir, these must be nervous times. Global drought is shrinking rivers and lakes, revealing much that had been hidden below the surface.

Hunger stones

As rivers run dry in central Europe, they reveal a type of low-water mark particular to that part of the world, the so-called Hungersteine, or “hunger stones.” These rocks are only visible when water levels are extremely low. Over centuries, they have been interpreted as warning signs of imminent crop failures and even famine, and they were inscribed with dates or sayings marking the event.

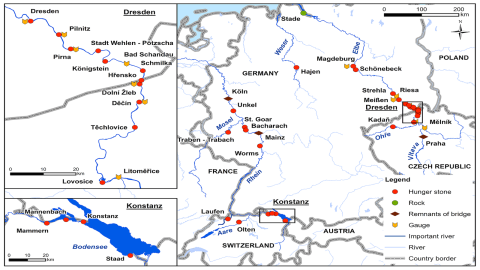

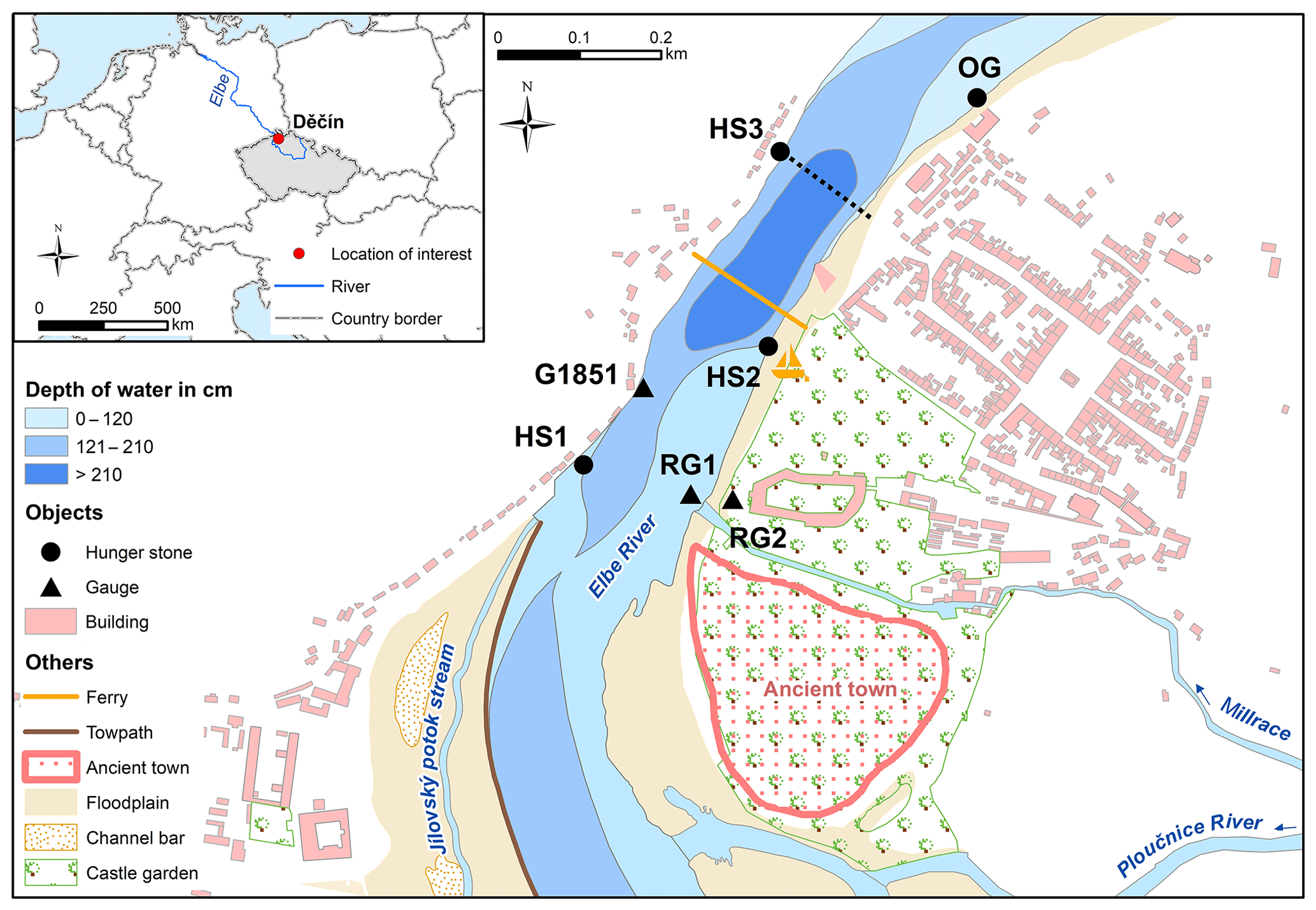

The most infamous hunger stone is the one in the Czech city of Děčín (in German, Tetschen) on the Elbe, near the German border, and not just because of its enormous size. As confirmed by drawings and photographs from the early 20th century, it is inscribed, rather ominously, with the slogan: Wenn du mich siehst, dann weine — “When you see me, weep.”

That inscription possibly dates back all the way to 1616. It follows a pattern. In 1904, a stone emerged in the Spree River near the village of Trebatsch, on which was inscribed: “When you see this stone again, you’ll cry, so shallow was the water in the year 1417.”

These hunger stones are a remarkable meteorological chronicle, from the age before standardized weather observations. Most of the inscriptions date from the 15th to the 19th century. The city archives of Pirna, Germany record a stone with the year 1115 engraved on it, but its exact location is no longer known.

Over the years, many hunger stones were removed as obstacles to shipping. The earliest remaining inscription is the one in Trebatsch.

Morbid tourism

The concept of hunger stones was brought to wider attention in the 19th century by newspapers and travelogues, the mass media of the time. In 1904, the Děčín stone became the target of daily tourist excursions, and had to be protected from destruction by a wall built around it. Thousands of postcards showing the stone were sent from the town all over the world. In the 1930s, an inscription in Czech was added, reading: “Girl, don’t cry and moan when it’s dry, water the fields instead.”

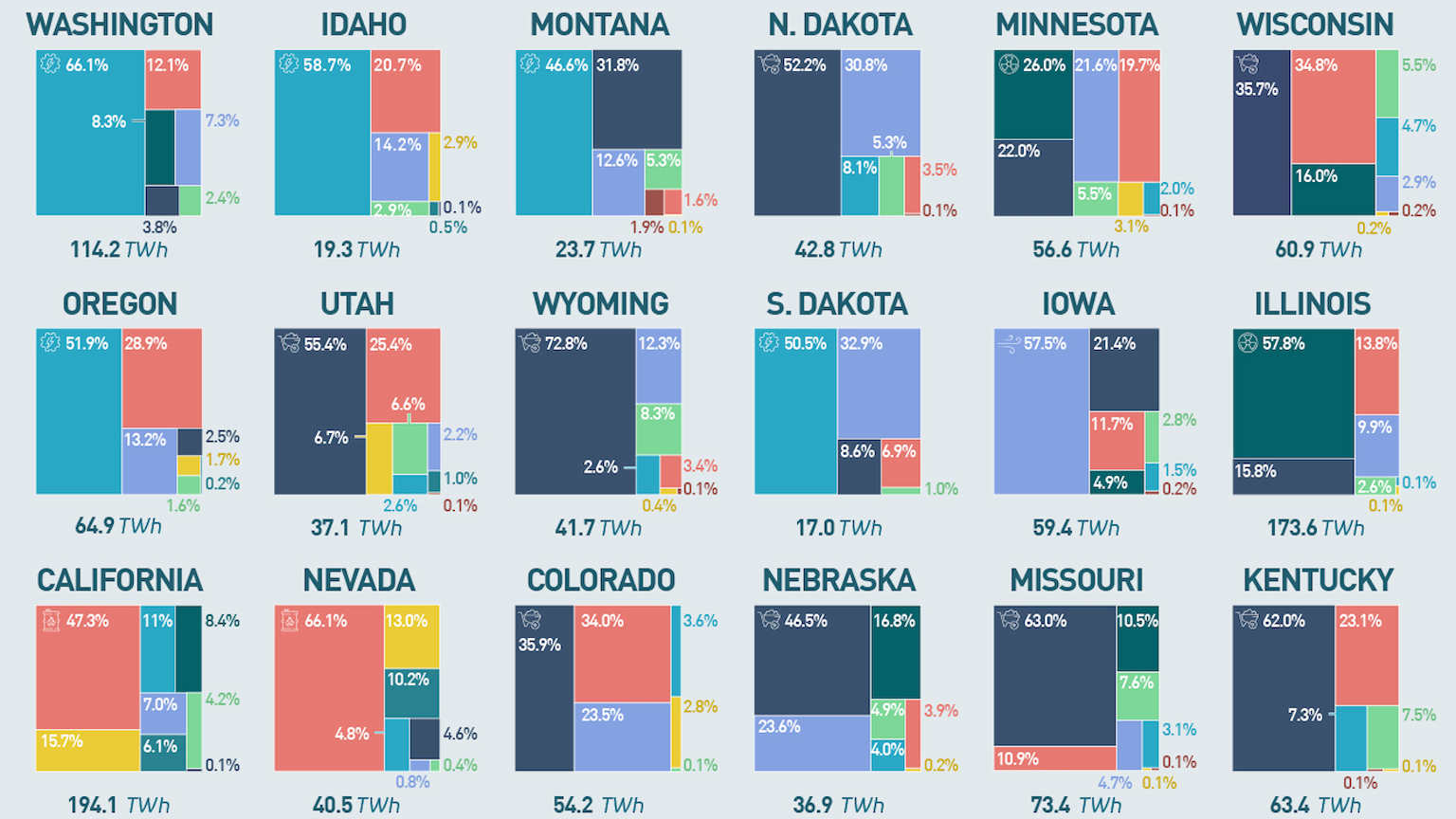

As the top map shows, the hunger stones are a phenomenon with a very limited geographic scope. More than two dozen hunger stones can be found in the Elbe, with a particular concentration on the stretch on either side of the German-Czech border.

There are a few stones in the Rhine, in particular on or near Lake Konstanz, near the German-Swiss border, as well as individual occurrences on the Mosel and Weser in Germany, and smaller rivers in northwestern Switzerland.

Messages from the past

Some of the more famous ones are gone now. The Altarstein or Elfenstein was a hunger stone in the Rhine near Bacharach, which in the 19th century was thought of as a Roman altar to Bacchus (hence the alternative Latin name “Ara Bacchi”). If it was visible due to low water levels, it was interpreted as predicting a good vintage. Victor Hugo saw and described it on his trip along the Rhine in 1840. Considered a danger to shipping, the stone was dynamited in 1850.

Other notable stones:

- Still surviving, a hunger stone in the Rhine near Worms-Rheindürkheim was first inscribed in 1857, and most recently in “Hunger Year 1947.”

- A rather more cheerful tradition accompanied the occasional emergence of a large stone in the Moselle, near Traben-Trarbach: Bottles of wine would be buried near its base, to be drunk when it became visible next time.

- A hunger stone in the Elbe near Bleckede reads: Geht dieser Stein unter, wird das Leben wieder bunter — “When this stone submerges, life becomes more cheerful again”.

- A stone in the Elbe near Magdeburg has a more contemporary message: Wenn du mich siehst, ist Klimakrise. August 2018 Greenpeace. — “When you see me, the climate is in crisis.”

This year is the most recent occurrence of droughts only a few years apart, bringing the hunger stones to the surface. Previous instances were 2018, 2015, and 2003. Thanks to globalized agriculture, none of these droughts has led to famines. But the increased frequency could be seen as an important, long-term manifestation of climate change in Central Europe.

Not everybody sees hunger stones as a bad omen. The townspeople of Meissen were so disappointed by the disappearance of their historical Hungerstein that they installed a new one in 2018.

Strange Maps #1165

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].