DNA analysis reveals when and where horses entered America from Europe

- Historical literature says the horses of Spanish colonizers came from southern Europe.

- A recent DNA analysis of an early colonial horse specimen in Haiti appears to confirm these claims.

- The analysis may also explain the origin of a mysterious feral New England horse breed.

North America is home to more horses than any other continent — over 19 million, according to some estimates. For most of human history, however, the Americas had no horses at all.

Archaeological evidence indicates that the genus Equus, which includes horses, donkeys, and zebras, evolved in the western hemisphere between 4 and 4.5 million years ago before spreading to Eurasia, only to disappear during a megafauna extinction event at the end of the Pleistocene.

Eurasia’s horses survived this extinction event, going on to influence the rise — and fall — of numerous civilizations. The genus’ millennia-long trip around the globe concluded in the late 15th century, when European explorers unknowingly returned the domesticated horse to its ancestral home.

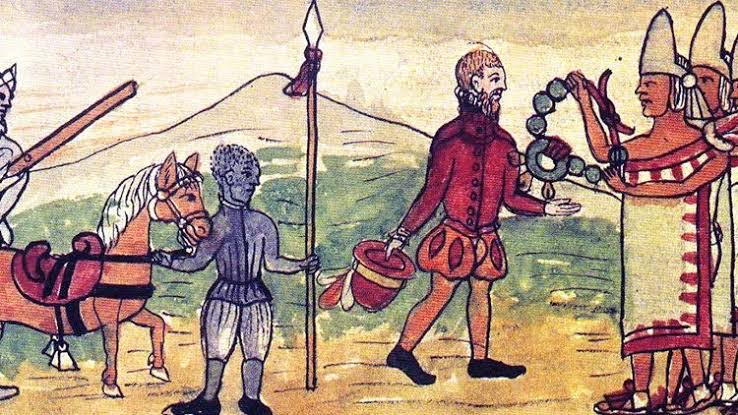

From here, horses went on to change life in the Americas just as they had in Eurasia. They enabled Hernán Cortés and other conquistadores to venture deep into the American heartland, where the animals provided a strategic advantage against the native populations. Horses also played an important role in local post-Columbian economies, which still revolve heavily around ranching.

Although the reintroduction of horses in the western hemisphere is well-documented in historical literature (Cortés’ subordinate Bernal Diaz wrote at length about the steeds that accompanied them on their initial journey), the same cannot be said for archeological excavations or DNA analysis.

Horse fossils in the New World are hard to come by. They represent only 2.3% of early colonial animal remains found at the Ek’ Balam site in Yucatan. At the El Japón and Justo Sierra sites, both located in Mexico City, horse fossils are even rarer, representing 1.75% and 0.23% of the total remains, respectively.

Why are these numbers so low? Archeologists think it might have something to do with social status. The colonial sites mentioned above were once used as garbage dumps. Since horses were used for work and transportation rather than consumption, their bodies rarely ended up in the trash.

With that out of the way, the historical literature indicates that the first domestic horses were taken from the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and brought to the Americas via the Caribbean during the late 15th century. It’s plausible, but who’s to say these sources can be trusted?

To test the hypothesis, a team of researchers from the Florida Museum of Natural History, the University of Florida, and the University of Georgia sequenced the mitochondrial DNA of a late 16th-century horse found near Puerto Real, a colonial port in northern Haiti. Their study not only sheds light on the ancestry of American horses, but also lends credibility to a famous New World myth.

The horse of Puerto Real

If the historical literature is to be believed, the first horses were brought to the Americas by Christopher Columbus on his second voyage in 1493. In his book Historia general y natural de las Indias, the Spanish historian Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés writes that these horses boarded Columbus’ ship on the Canary Islands and were subsequently taken to La Isabela, a town located in what is today the Dominican Republic.

Given that most equids are highly adaptable, it did not take long for Columbus’ horses to spread throughout greater Hispaniola. Within just a few years, the population had grown from a handful of individuals into self-sustaining herds that produced so many offspring that Nicolás de Ovando — governor of the West Indies — could afford to cease importing horses from Iberia.

As the Spanish colonists dispersed into the western hemisphere, so did their horses. By 1520, equids could be found across the Mesoamerican mainland, which comprises the countries of Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Belize. Less than two decades later, horses were roaming as far north as Florida. Those separated from their owners turned feral, only to be redomesticated by the Native Americans of the Great Plains.

Horses could also be found in Puerto Real, where — alongside cows — they sustained the town’s population and economy. Of the 127,000 or so animal remains that have been identified in Puerto Real, however, only eight of them can be attributed to horses. For their study, the researchers from Florida and Georgia analyzed not a complete horse skeleton, but a single tooth — actually, a fragment of a single tooth.

Originally, this tooth fragment was attributed to a cow; researchers did not learn it belonged to a horse until they took a closer look at the DNA embedded within. More so than historical literature, DNA gives us a straightforward and highly detailed impression of the ancestry — and, consequently, distribution — of horses in early colonial America.

The presence of a specific mutation in its mitochondrial DNA shows that the Puerto Real horse belongs to a branch of the equine family that is mostly found in Central Asia and Southern Europe, including the Iberian Peninsula. The branch encompasses a number of breeds, from Caspian ponies to the Maremmano horses of Italy and the Akhal Teke of Turkmenistan. One mystery solved.

The mystery of the Chincoteague ponies

The modern-day breed most closely related with the Puerto Real horse is the Chincoteague pony. Also known as Assateague horses, these wild equids can be found on islands off the coast of Virginia and Maryland. Their striking appearance — short, stout legs, thick manes, and large bellies — may have resulted from the need to adapt to the harsh environments of and limited resources available on their island homes.

While Chincoteague ponies have been extensively studied by conservationists, it is still unclear how they ended up off the New England coast. Oral traditions from the region, popularized by a 20th-century children’s novel called Misty of Chincoteague, claim their ancestors survived a colonial shipwreck.

This legend was previously contested by historians. Since the first British settlers of Virginia and Maryland made no mention of a feral pony population living on the islands, it seems likely that the Chincoteague ponies arrived sometime after the British did. However, because the DNA of the ponies and the Puerto Real horse differ by only six mutations, the legend may have some truth to it after all.

That’s the most exciting possibility, at least. But there is also another, more plausible scenario as well. “Beyond folk stories,” the study concludes, “affinities between early Caribbean horse breeds and the Chincoteague ponies may reflect Spanish efforts to colonize the Atlantic coast of North America.”