How Cameroon’s biggest lakes exploded — and killed 1,800 people

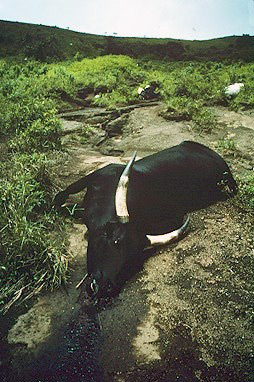

- In 1984, a lake in Cameroon exploded, killing nearby people and animals. In 1986, it happened again, killing some 1,800 people.

- Scientists from all around the world came to investigate. The culprit was carbon dioxide at the bottom of the lakes.

- A pipe was installed to remove the carbon dioxide, hopefully preventing another tragedy.

On August 15, 1984, the 72-year-old Abdo Nkanjouone was biking alongside the shores of Lake Monoun, a bone-shaped crater lake in the country of Cameroon, when he came across a pickup truck parked on the side of the road. Inside the truck was the limp and lifeless body of Louis Kureayap, a local priest.

Nkanjouone got back on his bike to look for help. Further down the road, he found another dead body, this one propped up on a motorcycle. A thoroughly freaked out Nkanjouone dismounted and continued on foot. Around the bend he encountered a flock of sheep, lying sideways in the grass. Beyond that, more parked cars, all containing dead passengers.

At first, the locals suspected that the mysterious murders at Lake Monoun had been politically motivated, part of a ploy to overthrow the government. Suspecting another, non-human culprit, the U.S. embassy in Yaoundé, Cameroon’s capital, sent volcanologist Haraldur Sigurdsson to investigate the lake and its surroundings.

Sigurdsson found no evidence of foul play, though he could not find any evidence of a volcanic eruption either. There were no sulfur compounds in the lake, nor did he detect an increase in water temperature or a disturbance in the lakebed. He did, however, discover that the water at the bottom of Lake Monoun contained an extremely large amount of carbon dioxide.

Suddenly, the pieces of the puzzle started falling into place. The local priest, the motorcyclist, the other drivers, and the sheep had not been planning a coup d’état. Rather, they appear to have died by inhaling carbon dioxide released from the lake. Authorities were convinced that Mother Nature would not repeat this freak accident anytime soon; Sigurdsson was not so sure.

The eruption of Lake Nyos

A second, bigger and deadlier eruption took place two years later at Lake Nyos, located 60 miles north of Monoun. Ephriam Che and Halima Suley, two of the survivors, shared their experience with Smithsonian Magazine. At around 9:00 pm, Che heard what sounded like a rockslide, after which a strange white mist began to spread from the lake.

Che’s farm stood overlooking the lake. Suley, a cowherd, was near its shore when the sound of the rockslide thundered through the valley. A strong wind carried the white mist from the water, causing her to lose consciousness. When she came to, the blue lake was dull red, one of the nearby waterfalls had run dry, and all the songbirds and insects were quiet.

“Some 1,800 people perished at Lake Nyos,” the Smithsonian Magazine surmises. “Many of the victims were found right where they’d normally be around 9 o’clock at night, suggesting they died on the spot. Bodies lay near cooking fires, clustered in doorways and in bed.” It was Monoun all over again, but on a much larger scale.

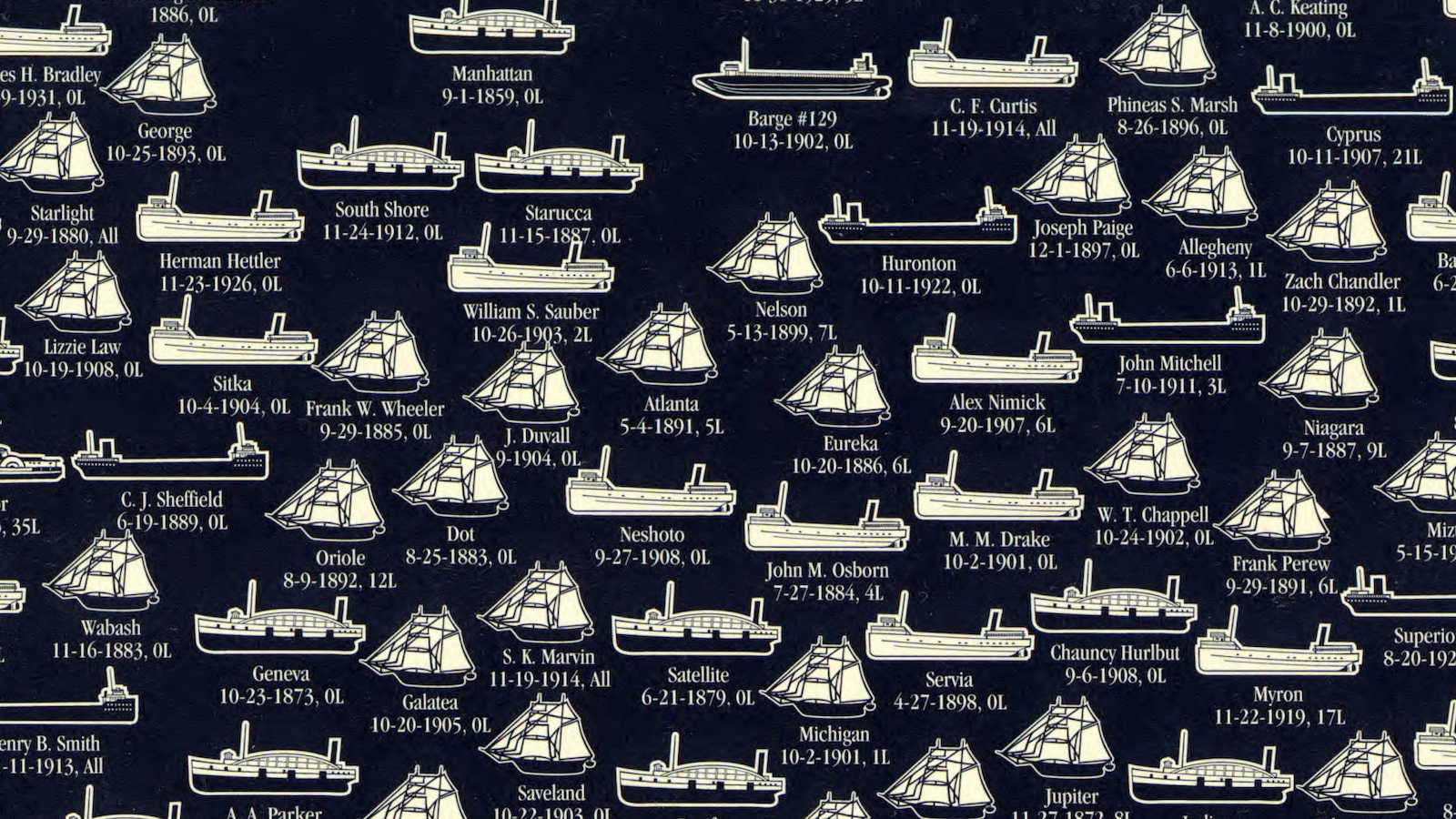

The bodies of these 1,800 people — including Suley’s four children and nearly 1,000 residents of Che’s village — were buried in mass graves by the Cameroon army. The cattle carcasses, which numbered in the thousands as well, were left where they collapsed, rotting, bloating, and decomposing in the scorching Cameroon sun.

A giant soda can

When Sigurdsson returned from Monoun, he turned his thesis — that the eruption was a consequence of carbon dioxide buildup from underground magma — into a research paper. The volcanologist later submitted this paper to Science, where it was rejected for publication due to its lack of concrete evidence.

The editors were also not particularly interested in the topic, but that changed after Lake Nyos. Alarmed by the towering death toll, researchers from Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Britain, and Japan flew into Yaoundé to build upon Sigurdsson’s hypothesis. Thanks to greater manpower and resources, they ended up making valuable new discoveries.

Nyos, like Monoun, rests on a crater of rubble formed by previous volcanic eruptions. The lake’s carbon dioxide either comes directly from this rubble or from magma further below. Due to a combination of current, pressure, and climate, the carbon dioxide cannot escape, causing it to accumulate at the bottom of the lake.

Smithsonian Magazine compares Lake Nyos to a giant soda bottle, one that is shaken for centuries without ever taking off the cap. When this cap was, at last, removed, possibly one billion cubic yards of carbon dioxide climbed into the air and into the surrounding area. The people and animals died from asphyxiation — lack of oxygen.

This leaves just one question: What took the cap off? Che and Suley’s testimony suggest that it was a rockslide. Researchers noticed a cliff next to the lake showing signs of recent sliding, and giant boulders sinking to the bottom certainly could have opened up a way for the carbon dioxide to escape. Perhaps nature had employed a similar detonator at Monoun.

Preventing the next eruption

Once the researchers understood what caused Monoun and Nyos to explode, they had to figure out how to prevent them from exploding in the future. The carbon dioxide at the bottom of the lakes had to be removed. But how? They considered dropping bombs, using lime to neutralize the gas, and installing a pipe underneath the lakes that could remove it.

The third option looked the most promising, though not everyone believed that it would work. The geologist Samuel Freeth worried that a leak in the pipe would allow the bottom water to mix with the surface water, causing yet another catastrophe that would not only endanger the local population but also destroy their costly infrastructure.

There was another problem, this one money related. Though Cameroon is among the wealthier countries of Africa, its government would not be able to afford to install the pipe, much less maintain it over a prolonged period of time. The researchers turned to international aid for financial assistance, but were unable to secure the necessary capital.

In 1999, 13 years after the eruption at Lake Nyos took place, the researchers managed to begin construction thanks to a grant from the U.S. Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance, who lent them half a million dollars. The pipe — 5.7 inches in diameter and 666 feet in length — is still in operation today, pumping an estimated 5,500 tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each year.

Its architects have said the pipe would take between 30 and 32 years to render the area around Lake Nyos safe and habitable again. Critics say this time frame is far too long, and that additional pipes could speed up the process. Speed is key, as survivors of the Nyos eruption and their families are now moving back toward the lake, eager to return to the home that was taken from them.