Ask Ethan: Is Antimatter Sticky?

It should be just as sticky (or non-sticky) as normal matter. Here’s how we know.

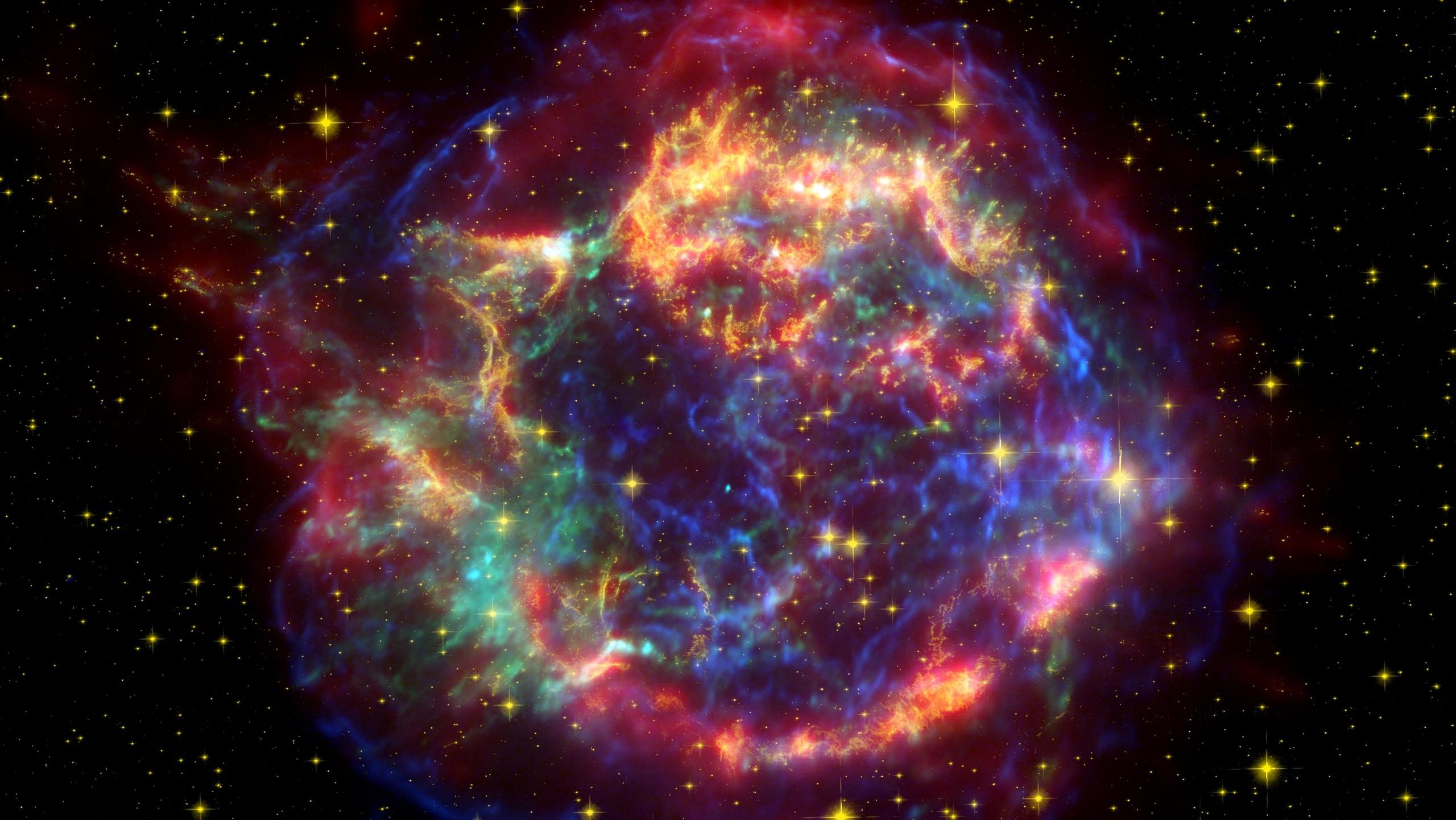

Not only here on Earth, but everywhere in the Universe that we look, we find structures on scales large and small that are all made out of matter. Matter, that is, as opposed to antimatter. Every galaxy, star, planet, and collection of gas and dust that we’ve found is made of matter, exhibiting the exact physical and chemical properties familiar to us here on the also-made-of-matter planet Earth. But what if conventional things were made of antimatter instead? This question came up in my household earlier this week, when the following exchange occurred:

Jamie: Uck! <disgusted noise> What is this <sticky hands gesture> on the back of this chair?

Me: <raises eyebrows> I don’t know. <pause> Is it antimatter?

Jamie: <thoughtful consideration> I don’t know. Is antimatter sticky?

Me: <reflexively> Gross! And also, yes.

The answer really is yes. Antimatter is sticky: just as sticky as normal matter is. Here’s how we know.

When we talk about the conventional properties of material things — like how sticky, elastic, bouncy, or bendy they are — these are bulk, large-scale, macroscopic traits. In science, we call these physical properties: you can measure them without changing the properties of the substance. When you touch sticky bread dough, an elastic rubber band, or a bendy tree branch, they stay sticky, elastic, or bendy even though you touched it.

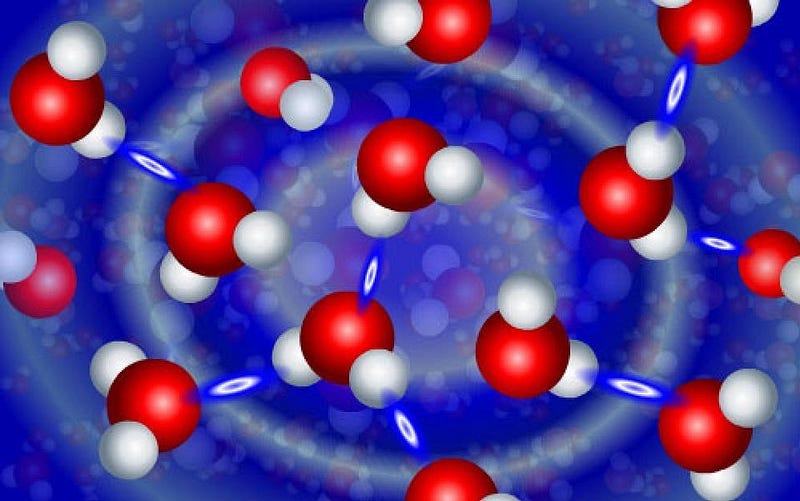

But if we ask the question of “what causes those physical properties,” we have to go all the way down to the microscopic world to understand what’s truly happening. Down far below the limit of what the human eye can see, at microscopic scales, everything is made of atoms. These atoms bind together into molecules, which in turn bind together through inter-atomic forces to make up the large-scale objects we interact with in our conventional experience.

When something feels sticky to the touch, it’s because the electrons in the material you’re touching interact with the electrons in your fingertips in a particular way that give rise to the property we associate with stickiness. Everything that we associate with that “sticky” sensation is based on how the electrons in those atoms bind together: covalently, ionically, in mixtures and suspensions and solutions, and through the hydrogen bonds between them and in other materials.

You can freely substitute any other physical property you like and any other interaction you like for “stickiness” and your fingertips: properties like color and how the emitted/reflected photons interact with your eyes. In every instance, the molecules and their interactions are what we experience, but the individual atoms and the atomic transitions made by the electrons in those atoms determine the properties and interactions of molecules.

That brings us to an interesting crossroads. We don’t have large quantities of stable antimatter to work with and manipulate. If we did, we could build anti-molecules and macroscopic objects out of it, and test out how it interacts with other forms of antimatter. But that’s still a dream for physicists and materials scientists interested in investigating antimatter. In fact, for a long time, all we had were theoretical calculations to guide us.

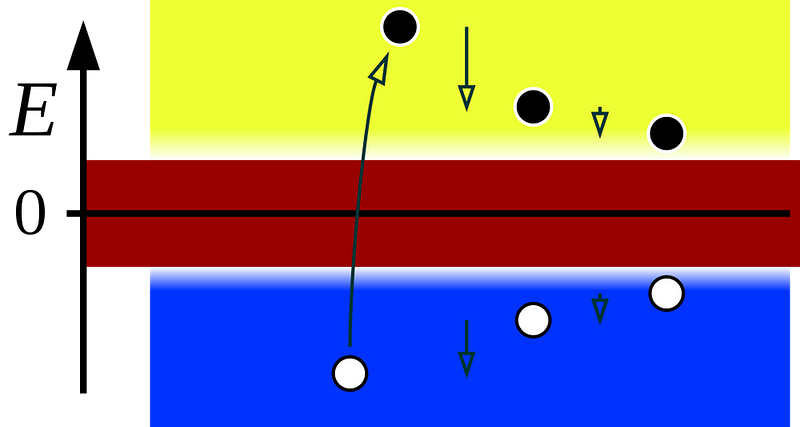

The idea of antimatter is 90 years old, and arose at first from purely theoretical considerations. The earliest equation describing individual particles in quantum mechanics — the Schrödinger equation — was incompatible with Einstein’s Special Relativity: it didn’t work for particles moving close to the speed of light. Early attempt to make the Schrödinger equation relativistic gave negative probabilities for some outcomes, which is nonsense: all probabilities need to be between 0 and 1; negative probabilities don’t make physical sense.

But when the first relativistic equation came out that accurately described the observable properties of the electron, it had this weird property: the electron was only one possible solution to the equation. There was another solution that corresponded to an “opposite” state, where everything about the electron was flipped. The spin was flipped, the charge was flipped, other quantum numbers were flipped, too.

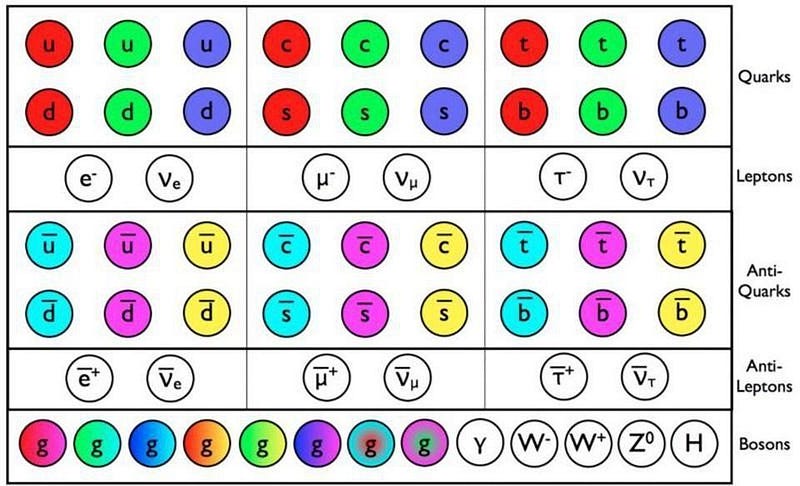

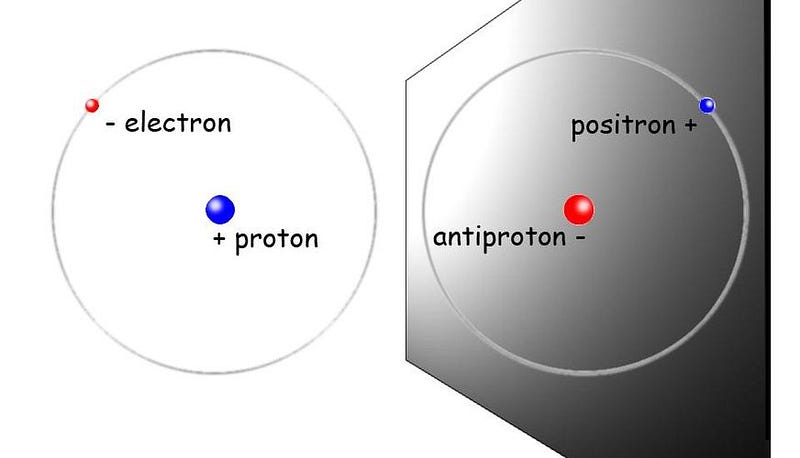

The correct interpretation of this was resisted at first, but turned out to be true: there should be an “anti-electron” out there in the Universe, which would annihilate with any electron it encountered into pure energy (photons). This antiparticle, now known as a positron, turned out to be the first example of antimatter we’d ever discover. More than 90 years later, we now know that every matter particle has an antimatter counterpart: an antiparticle.

The problem is that the only way to create antimatter, at least in any meaningful quantities, is by smashing things together with so much energy that they spontaneously produce new particle-antiparticle pairs via Einstein’s famous mass-energy equivalence relation: E = mc². For a long time, this brought along the problem that all antimatter particles, because they were created with so much energy, always moved close to the speed of light.

They’d either decay away or annihilate with the first matter particle they encountered, which produces great results for particle physicists but very bad results for anyone wanting to know whether antimatter had the same properties as matter. In theory, it should. While the charges and spins (and some other quantum properties) should be reversed, in terms of assembling anti-atoms, anti-molecules, and even anti-humans, the physics should lead to identical results.

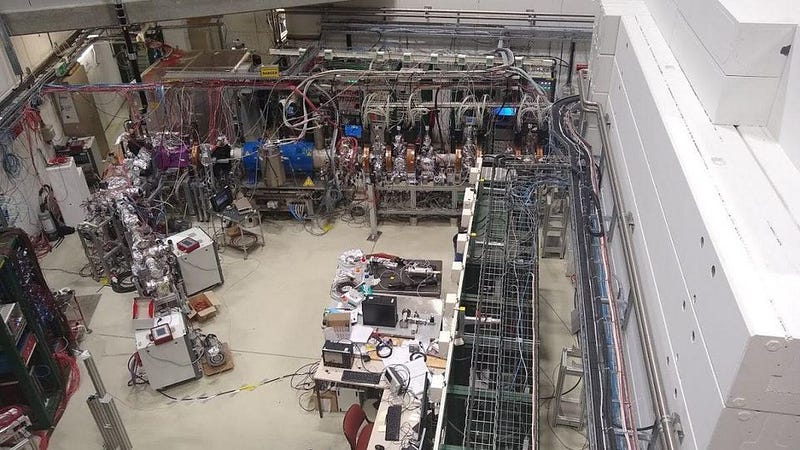

But recently, we’ve gained the ability to test out, experimentally, how antiparticles bind together. Over at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research and the home of the Large Hadron Collider, an entire large complex is devoted to the creation and study of antimatter. It’s known as the antimatter factory, and its specialty involves not only producing low-energy antiprotons and low-energy positrons, but in binding them together to form anti-atoms.

This is where things get really interesting for anyone interested in determining whether antimatter is just as sticky as regular matter. If antimatter plays by the same analogous rules as normal matter, then anti-atoms should exhibit certain properties that are identical to the ones that normal atoms do. They should have the same energy levels, the same (anti-)atomic transitions, the same absorption and emission lines, and should bind together to form anti-molecules the same way atoms form normal molecules.

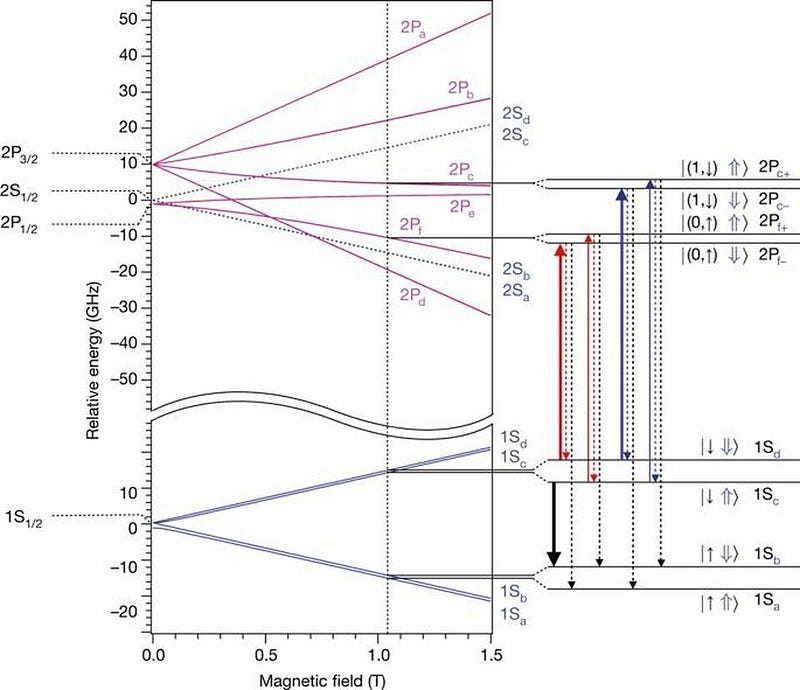

In 2016, scientists at the ALPHA experiment at CERN’s antimatter factory measured the atomic spectra of antihydrogen for the first time, fully expecting that it would absorb and emit photons at the exact same frequencies that normal hydrogen does. The next year, they were able to measure the hyperfine structure of the anti-atom’s energy levels, and again got results that matched normal matter’s energy levels incredibly well: to within 0.04%.

Additional measurements have now been performed to incredible precision, and each time, the result has been the same: positrons in anti-atoms have the same quantum properties, including the same transitions and the same energy levels, as electrons do within normal atoms. Heavier anti-nuclei have been created as well, and at every turn, we get the same result: anti-atoms have the same electromagnetic properties as their normal atom counterparts.

The first precision tests of antimatter have been in for a few years now, as the 2010s were a revolutionary decade for them. At every turn, wherever we’ve been able to look, the building blocks of what would be normal antimatter:

- antiprotons,

- antineutrons,

- the heavier nuclei formed by antiprotons and antineutrons bound together,

- and positrons,

bind together and exhibit quantum transitions that are identical in every measurable way to normal matter.

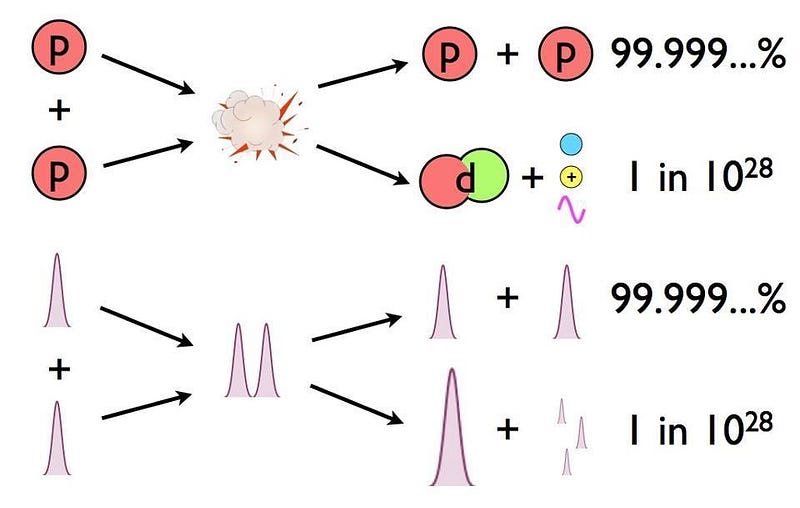

You might wonder if there’s anything significant that’s allowed to be different under the laws of physics as we know them, and there’s one little bit of wiggle room: radioactive decay. The weak nuclear interactions are the only interactions that are allowed to violate some of the symmetries between matter and antimatter, and it’s possible that some processes are slightly different for matter and antimatter. For example, two protons, when they fuse together in the Sun, have a 1-in-10²⁸ chance of producing a deuteron. That value may not be identical for antiprotons and an anti-deuteron.

If we were made of antimatter instead of normal matter, along with everything else on Earth, the physical and chemical properties of everything we know would remain unchanged. Whatever that mysterious, sticky substance on the back of your chair might be, the antimatter counterpart of it is going to be equally sticky. The same is true for its elasticity, bounciness, bendability, color, or any other conventional property you can measure.

Antimatter, as far as we can experimentally and observationally tell, interacts with other forms of antimatter exactly the same way that normal matter interacts with other forms of normal matter. If some configuration of normal matter is sticky, the antimatter counterpart of that is going to be equally sticky. Only, if you’re going to try and touch it to verify, make sure that you’re made of antimatter as well. Otherwise, the results are going to be much more explosive than sticky.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.