Messier Monday: The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster, M68

A surprising globular cluster found directly opposite to the galactic center!

“A friend who is far away is sometimes much nearer than one who is at hand. Is not the mountain far more awe-inspiring and more clearly visible to one passing through the valley than to those who inhabit the mountain?”

-Khalil Gibran

With a nearly full Moon not only out tonight, but located right in the Virgo Cluster, you’re going to have a terribly difficult time viewing one of those galaxies this fine Messier Monday. But the clusters of the night sky — both the open star clusters and the globular clusters — still make for spectacular viewing, and tonight’s object is one-of-a-kind!

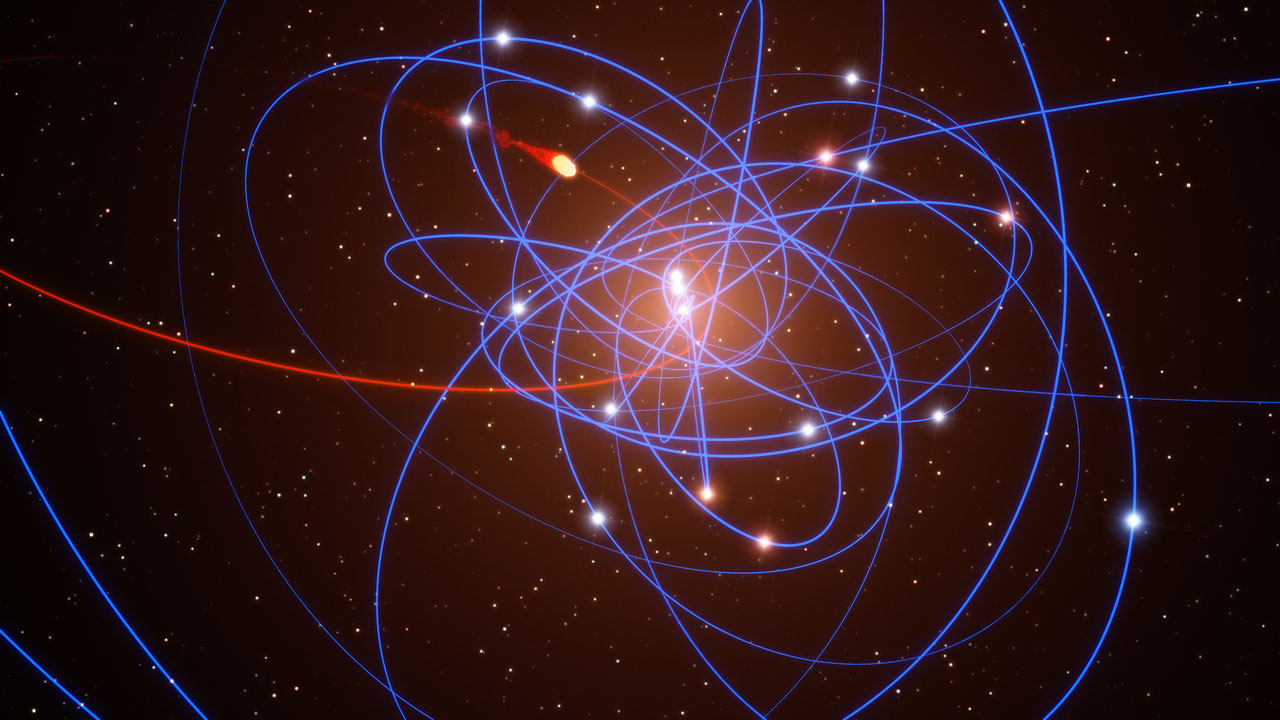

While the 100+ globular clusters in our galaxy are roughly distributed spherically in a halo around our galactic center, we are located in the plane of the disk, about 27,000 light-years out. How unusual, then, would it be to find one of these objects in the exact opposite direction to the galactic center?

Yet 180° away, there it is: Messier 68. Here’s how to find it.

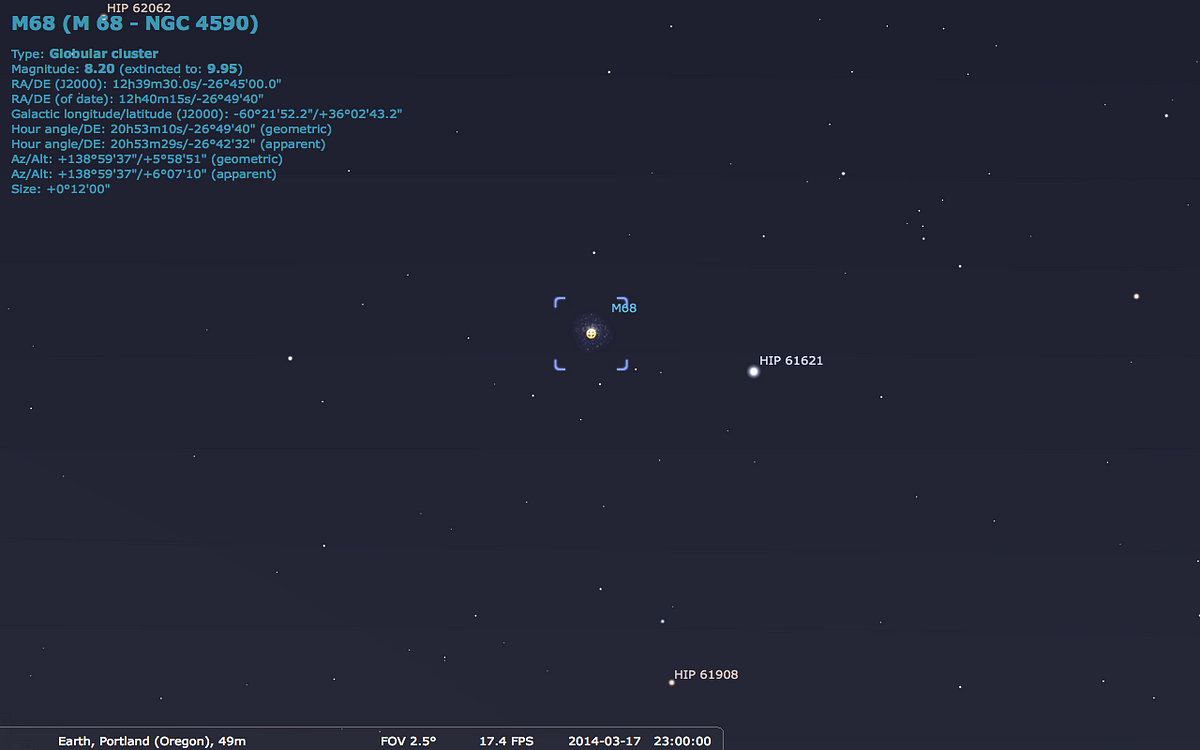

You can always navigate from the Big Dipper by following the “arc” of the handle to the bright orange giant, Arcturus, and then “speed on” to Spica, the bright blue star beneath. Tonight, you’ll also find Mars and the Moon nearby, but if you continue speeding on, at about 11:00 PM, you’ll encounter a few other prominent stars that will be your guide to Messier 68.

If you keep speeding on, you’ll run into the star β Corvi, which isn’t quite as bright as Spica but still is prominent, and can be found as the “lower-left” star of the almost-square in the constellation of Corvus. There will be two equally bright (but bluer) stars prominently above it: Algorab and Gienah, and if you trace from those stars “down” through β Corvi, you’ll come to a faint, but still naked-eye star: HIP 61621.

Train your telescope (or binoculars) on HIP 61621, and less than half a degree away, you’ll find the faint, extended but brilliant globular cluster: Messier 68. At least, it’s brilliant in larger telescopes; smaller ones are unable to resolve it into stars. Messier — the cluster’s discoverer — had the same problem:

Nebula without stars below Corvus & Hydra; it is very faint, very difficult to see with the refractors; near it is star of sixth magnitude.

It is faint, and the brightest individual stars in it are as much fainter than HIP 61621 as that barely-visible star is from the brightest ones in the sky! It’s pretty cool that a globular cluster like this is actually found among the Messier objects; if it were in, say, the same direction as the galactic plane, it would have been invisible to Messier against the dense backdrop of stars!

As it is, however, its details can be brought out exquisitely with the right equipment.

The stars found in this cluster are — like the majority of globular clusters — very old, very metal-poor, and much dimmer (on average) than the typical stars found in our galaxy. These things all go hand-in-hand:

- The stars are old because globular clusters tend to form when the Universe was much younger, and the ones that are still around tend to have been the most massive ones.

- They’re very metal-poor because they formed out of gas that had only been enriched very slightly by prior generations of stars.

- The stars inside are dim because the brightest stars — the O, B, A, and even most of the F-class stars — have all burned out by now!

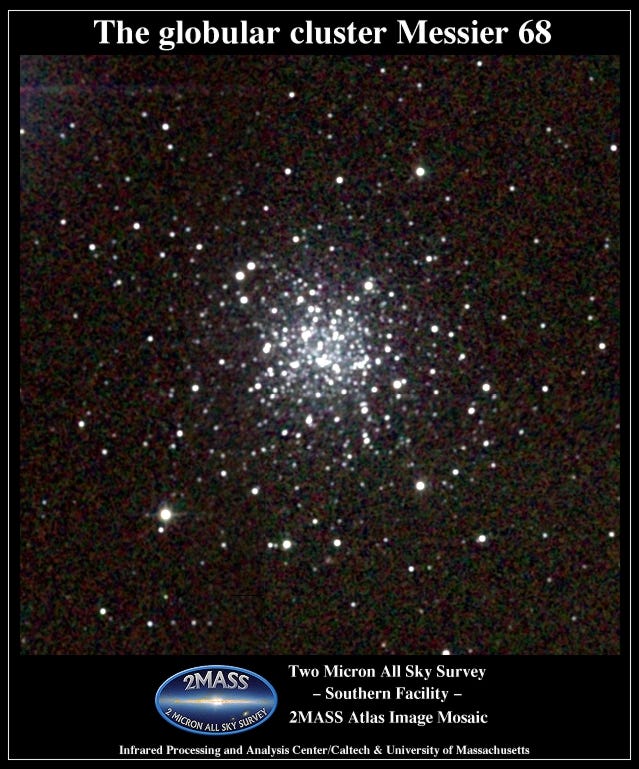

And what we’re left with is a glittering jewel-box of ancient stellar relics from the young Universe.

Up until the mid-20th century, there were claims that this cluster consisted of maybe 200-to-250 stars. Of course, that would be crazy for a globular cluster, which normally has at least tens-of-thousands!

At 33,000 light-years distant (so, about 60,000 light-years from the galactic center), it’s certainly one of the less impressive, less concentrated globulars, rating a concentration class of the rather loose X on a scale of I to XII. It’s also one of the most metal-poor clusters of all, containing just 0.6%-to-0.7% the amount of heavy elements that the Sun does! This is incredibly low, even for a globular cluster, and is suggestive that perhaps — as some have suggested — that it didn’t originate in the Milky Way, and was captured from a galaxy we absorbed long ago.

But a look at this cluster in the infrared teaches us something else interesting.

There are maybe 250 giant stars inside, but thousands more. Based on the motion of the stars we see, the total mass of the cluster is probably around 200,000 times the mass of our Sun, telling us that there are probably hundreds of thousands of stars inside.

It’s also headed towards us at about 112 km/s, which really just tells us it’s moving towards the galactic center; this is totally expected behavior for a globular cluster in orbit on the outskirts of our galaxy.

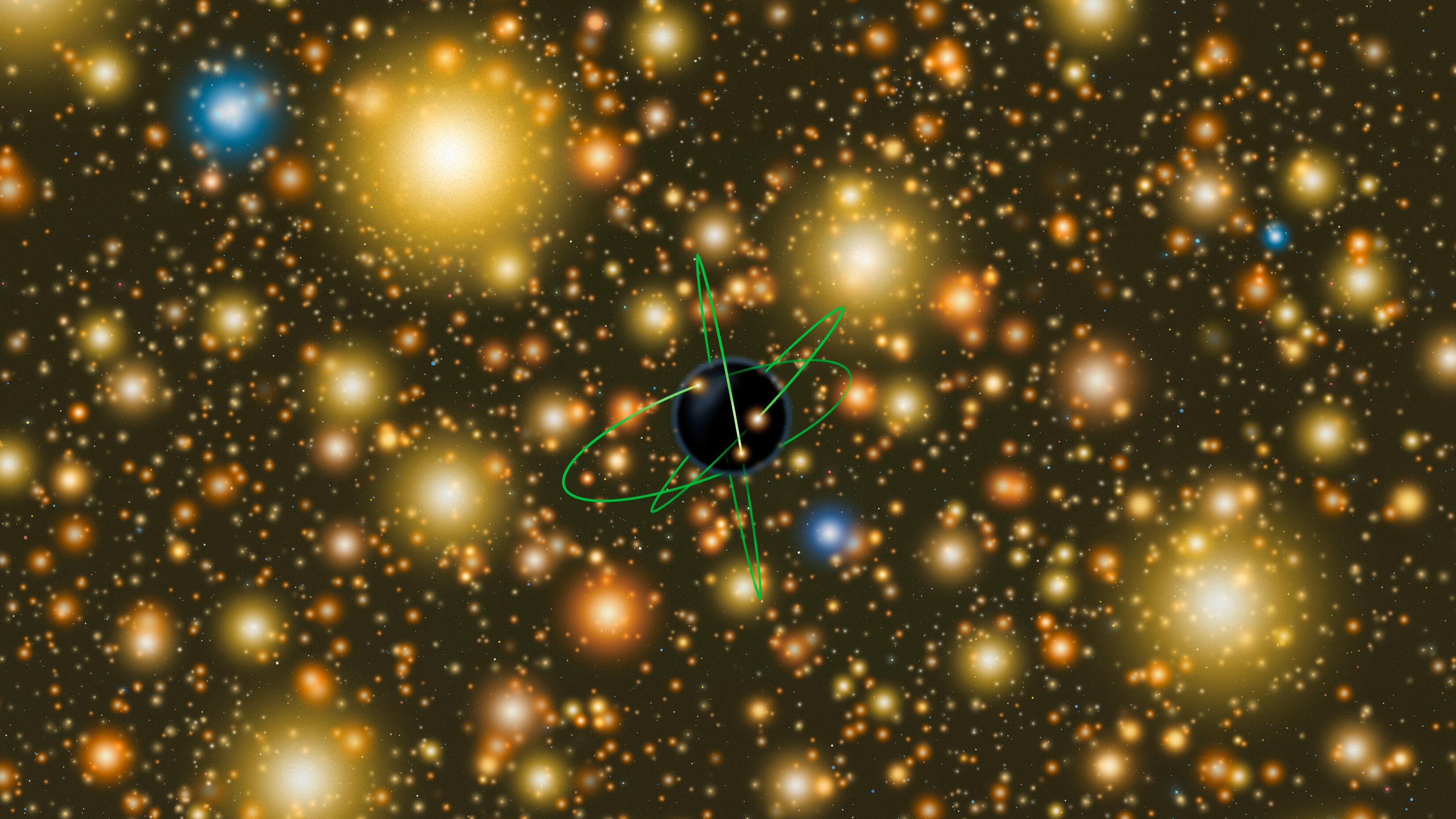

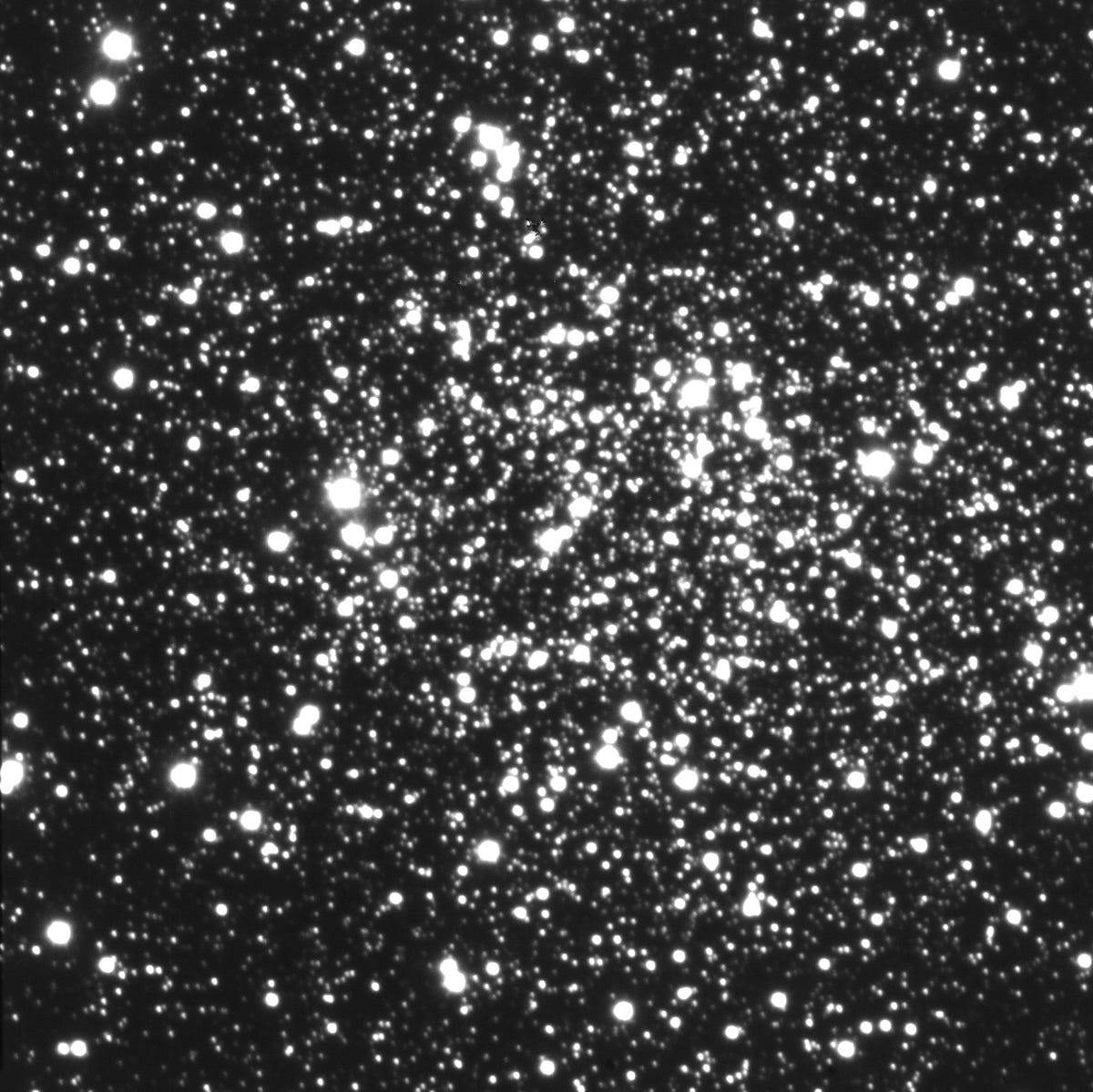

But the core of this globular cluster — even though it’s a relatively low-concentration cluster — is still so dense! This image from the Very Large Telescope identified many thousands of stars in the central three light-years of this galaxy, which is very impressive.

But the best images of the core of this cluster come from the Hubble Space Telescope, which has observed it multiple times.

In the innermost 30-or-so light-years, shown here (for a cluster that’s more than 100 light-years across), you can really see how many stars there are in this incredibly small region of space; it measures just a 20th-of-a-degree on a side!

Still, I prefer this Hubble image of the same region, which showcases the relative brightness of what’s inside.

And finally, for those of you who are fans of slices-and-flythroughs of the spectacular Hubble images in full resolution, here’s the penultimate one in full, glorious resolution!

If you enjoyed today’s Messier Monday, why not take a look back at all the previous deep-sky wonders:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M68, The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster: March 17, 2014

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M98, A Spiral Sliver Headed Our Way, March 10, 2014

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

Next Monday, the Moon will be out of Virgo, and we’ll take a look at one of the highlights of the greatest galaxy cluster in the vicinity of our Universe! Until then, enjoy the night sky!

Enjoyed this? Have a comment? Leave one on the Starts With A Bang forum at Scienceblogs!