Turn any place on earth into a New York street corner

Credit: ExtendNY

- Manhattan’s street grid is famously regular and predictable. What if you extended it across the globe?

- This web tool does exactly that, and in the process, turning New York into the world’s first, last, and only “planetary city.”

- But grids are square, and the world is not. Somewhere in Uzbekistan, global Manhattan goes haywire.

Can’t afford to live in New York? Yes, you can, and it won’t even cost you a penny. In fact, you don’t even have to move there. The Manhattan gridiron will come to you instead!

New York, but from the comfort of your own home

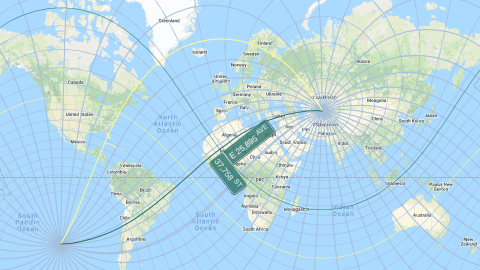

A nifty website called ExtendNY has rolled out the iconic street grid across the entire planet. You can now enjoy a real New York address at the corner of Such-and-such Street and This-and-that Avenue from the comfort of your own home.

New York may no longer be the biggest city in the world – Tokyo snatched that title somewhere in the second half of the 20th century – but the Big Apple still has a better claim than most other cities to be the Capital of the World.

It’s a city built by immigrants, home to people of every persuasion and complexion, speaking languages from all across the globe. Countless screens reflect the city’s skyline, cityscape, and frenetic energy back to the rest of the world.

Even first-time visitors feel oddly at home between the familiar bridges, yellow cabs, and skyscrapers of Manhattan. Plenty of locally-set movies and series – in turn glitzy or gritty – have seen to that.

So it feels weirdly appropriate that ExtendNY, devised in 2011 by Harold Cooper, should allow New York to cover the entire planet and become not just the capital of the world, but a synonym for the world itself. New York is the first, last, and only planetary city the planet needs.

Boris Johnson and Angela Merkel, New York socialites

As a result, a lot of famous addresses the world over get an equally iconic New York one as well. The British Prime Minister, currently Boris Johnson, famously works out of Number 10 Downing Street in London. Ah yes, but that’s also on the corner of 63,708th Street and E 10,894th Avenue in New York.

His opposite number in Germany, Chancellor Angela Merkel, resides in the Bundeskanzleramt, overlooking the river Spree in Berlin. Or, when she daydreams of a slightly different life: the corner of 75,490th Street and E 11,126 Avenue in New York.

A new meaning to the Upper East Side

Even natural features don’t escape global New York. The top of Mount Everest, on the border of China and Nepal? The corner of 96,104th Street and 67,128th Avenue. The actual North Pole? The map looks a bit funny, but the address is credible enough: the corner of 58,725th Street and 12,993 Avenue.

Similarly, the Eiffel Tower, the Ka’aba in Mecca, or your own place – all are now distant suburbs of NYC.

Uzbekistan: the nexus of the universe

Because the grid is rectangular and the earth is not, there are a few points where Global New York runs into bizarro territory. In remotest Uzbekistan, ExtendNY’s gridiron arrives at a strange point, where the succession of streets have condensed into one that consists only of a single point – 127,001st Street – which intersects with all of Global New York’s Avenues. That mind-bending street corner is mirrored by a similar opposite in the South Pacific. As Kramer suggested, this could be the nexus of the universe — in Global New York, anyway.

Although Manhattan’s grid may strike us as thoroughly modern, gridded cities are by no means a recent invention. In French, a grid plan is called a plan hippodamien, after the ancient Greek architect Hippodamus of Miletus (5th century BC), a.k.a. the ‘father of European urban planning’.

The loneliness of Stuyvesant Street

However, like most cities in the Old World, the oldest ones in the New World grew up unplanned. In New Amsterdam, which occupied the southern tip of Manhattan, the streets followed old native trails, cow paths, and property lines, and generally the lay of the land.

Stuyvesant Street is a poignant and lonely relic of one of several attempts to impose order on that chaos. Sitting awkwardly between 2nd and 3rd Avenues, it is one of the very few streets in Manhattan to be aligned almost perfectly east to west.

In the late 18th century, the City commissioned Casimir Goerck to subdivide its Common Lands, in the middle of Manhattan, into sellable lots. Goerck’s name is now largely forgotten, quite literally. The small street in the Lower East Side that once carried his name was rebranded Baruch Place in 1933. But his plan, in the words of historian Gerard Koeppel, is “modern Manhattan’s Rosetta Stone.”

Goerck oriented streets 29 degrees east of due north, in order to align with the shape of the island itself, and devised a standard of five-acre blocks, two features which would come back in the famous Commissioners’ Plan of 1811. Goerck’s East, Middle and West Roads would become 4th, 5th, and 6th Avenues. In fact, the Commissioners’ Plan is essentially an expansion of Goerck’s grid laid out over the Common Lands.

The Plan proposed a city grid north of Lower Manhattan, from Houston Street (pronounced “house-ton” and not “hyoos-ton”, by the way; then appropriately called “North Street”) up to 155th Street – with two exceptions:

- Greenwich Village, then independent from New York City, was excluded – hence the visibly different orientation of the streets in “the Village.”

- 10th Avenue went well beyond 155th Street, all the way up to the northern tip of Manhattan.

The Commission adopted Goerck’s gridiron as the most practical layout for the city, as “straight-sided and right-angled houses are the most cheap to build and the most convenient to live in.” In its predictability and repetition, the gridiron was a reflection of “republican” values such as plainness and uniformity, order, and equity.

In all, the Plan created about 2,000 city blocks. It took about 60 years for that grid to be filled in – but alterations were made, the biggest of which was the establishment of Central Park. Created in 1857 and completed in 1876, it runs from 59th up to 110th street, and from Fifth to Eight Avenues. It takes up 843 acres or just over 6 percent of the entire island of Manhattan.

From the 1860s onward, the grid was essentially extended northward, despite the fact that the difficult terrain necessitated some alterations.

Manhattan, Sartre’s “Great American Desert”

Broadway, which originally only went up to 10th Street, was eventually joined up with other roads north, until it reached Spuyten Duyvil at the top of Manhattan in 1899. Its angled intersections with the grid helped create some of New York’s most emblematic open spaces, including Times Square, Madison Square, and Union Square.

From the start, the plan had come in for harsh criticism. In more recent times, it’s been praised as visionary. Here are some put-downs by famous voices:

- Alexis de Tocqueville, the French philosopher famous for his observations of the newly independent U.S., criticized the Plan’s “relentless monotony.”

- Poet and journalist Walt Whitman wrote that “our perpetual dead flat and streets cutting each other at right angles, are certainly the last thing in the world consistent with beauty of situation.”

- And architect Frederick Law Olmsted, who would go on to design Central Park, lamented that “no city is more unfortunately planned with reference to metropolitan attractiveness.”

- “Rectangular New York,” in the words of writer Edith Wharton, is “this cramped horizontal gridiron of a town without towers, porticoes, fountains or perspectives, hide-bound in its deadly uniformity of mean ugliness.”

- Lamenting its “deadly monotony”, architect Frank Lloyd Wright called the grid a “man trap of gigantic dimensions.”

- In his essay on New York called “Manhattan: The Great American Desert,” French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre wrote that “amid the numerical anonymity of streets and avenues, I am simply anyone, anywhere, since one place is so like another. I am never astray, but always lost.”

And here is some of the praise that has been lavished on the grid:

- In his 1987 book Delirious New York, Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas called it “the most courageous act of prediction on Western civilization.”

- Earlier, his fellow Dutchman, the artist Piet Mondrian, had transferred his admiration for the vibrancy of the grid to canvas, as Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942-43).

- The Uruguayan architect Rafael Viñoly called it “the best manifestation of American pragmatism in the creation of urban form.”

- Hilary Ballon, curator of “The Greatest Grid” on the occasion of its bicentennial in 2011, said that “New York’s street system creates such transparency and accessibility that the grid serves as metaphor for the openness of New York itself.”

- “It may not be every urban planner’s beau ideal, but as a machine for urban living, the grid is pretty perfect,” said economist Edward Glaeser.

- Not all French philosophers hated Manhattan. “This is the purpose of New York’s geometry,” wrote Roland Barthes: “that each individual should be poetically the owner of the capital of the world.”

Welcome to / Bienvenue à Haussmanhattan

It’s doubtful whether it was Barthes’ words that spurred Mr. Cooper to devise his web tool; but thanks to ExtendNY, every place on earth is now a poetic extension of the capital of the world.

For another example of Manhattan’s global appeal, check out Haussmanhattan, a visual project by architect/photographer Luis Fernandes that mashes up the early 20th-century architectures of New York and Paris, after the latter’s renovation by Georges-Eugène Haussmann.

Check out ExtendNY here. For a slightly less ambitious plan to extend New York, check out Strange Maps #486: The Failed Plan to Build a “Really Greater New York”.

Strange Maps #1087

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.