The “perfect map” paradox: Why scientific models can never be complete

- Science can be thought of as a series of maps of nature, striving to be ever more complete, as models and theories evolve.

- However, just as no map can contain all of the territory’s information, our maps of reality will always be incomplete.

- The expectation that we can build theories of everything — complete maps of the Universe — is thus a misleading fantasy.

We humans map our lives with models of what we perceive and feel. As travelers exploring known and unknown territories, we rely on them for guidance. What is routine becomes so ingrained that we don’t even pay attention: “I know this land like the palm of my hand.” Novelty becomes like an edit to our maps, with new information updating how we see the world and ourselves in it. Science can be seen as a collection of maps being constantly updated as we learn more about what’s around us. But a map is always an approximation, an incomplete description of the world. Which begs the question: How do we know how good a map is? The Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges, in his brilliant allegorical style, summarized the situation in a one-paragraph short story, “On Exactitude in Science”:

…In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast Map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography. — Suarez Miranda,Viajes de varones prudentes, Libro IV,Cap. XLV, Lerida, 1658

The perfect map paradox

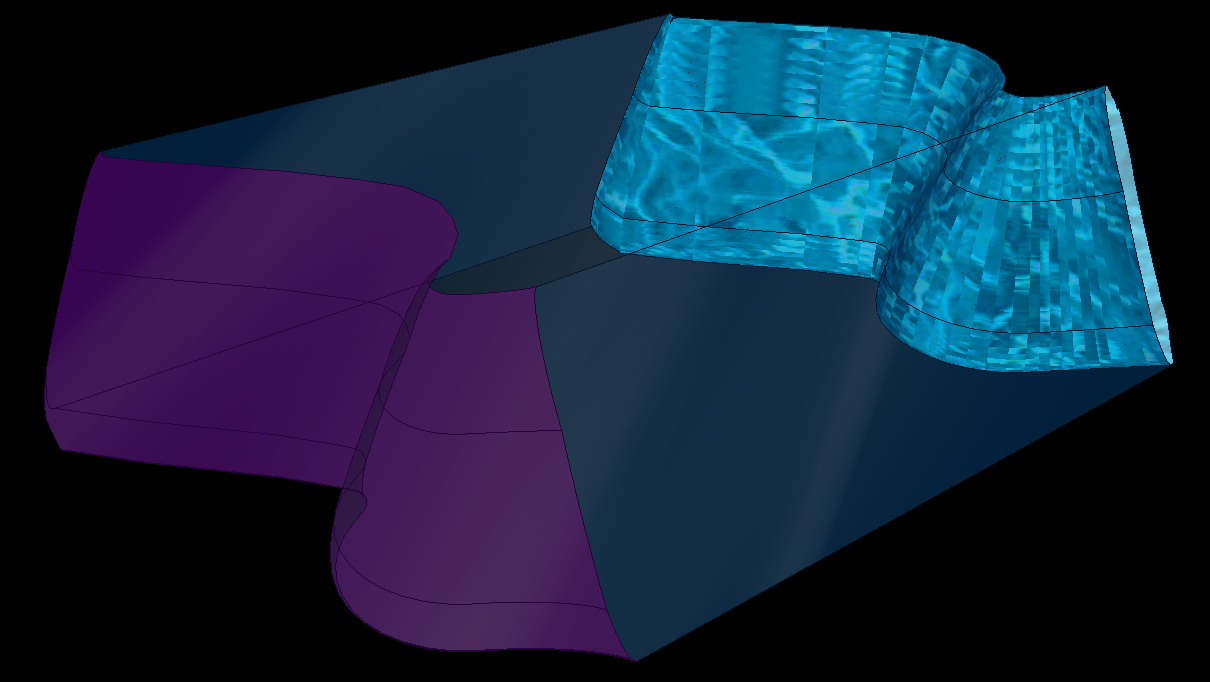

The only perfect map is one that reproduces precisely all the details of whatever it is mapping, or the “territory.” Hence the paradox: If the map is as large as the territory, it has no value whatsoever. A perfect map is as useless as it is impossible to create.

The title of Borges’s story, “On Exactitude in Science,” is purposely ironic. Borges is poking fun at scientists who believe, quite naively, that their scientific models and theories are actually producing a perfect map of reality. If science can be understood as a map, a representation of what we see of the world, then nature is the territory.

The analogy is extremely apt, capturing both the goals and the frustrations of science: We want to know as much as possible about the world and turn it into a description that we can share (the map). The more we know, the better the map is. However, as the French philosopher Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle noted in 1686, there is only so much that we can see of the world. Any map we produce is necessarily incomplete. “All philosophy is the product of two things only: curiosity and shortsightedness,” he wrote in his Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds.

There is tension between our curiosity to always know more and our myopic gaze, the impossibility of seeing all. This tension is a good thing, one that inspires our creativity and inventiveness. Our scientific instruments are tools of exploration, devices we develop to augment our view of the world, our reality amplifiers. Just as maps evolved as we learned more about Earth’s geography, our scientific understanding of nature evolved as we probed deeper into physical reality with our tools.

The danger, as Borges so cleverly admonishes us in his short story, is that our ambition can lead us astray. Unchecked, the urge to produce better and better maps of reality — intending to reach that final, perfect description of the territory — is a form of blindness. Borges, who suffered from cataracts that eventually made him blind, understood this better than most. Even in full sight, much of the world remains unseen.

A “final theory”

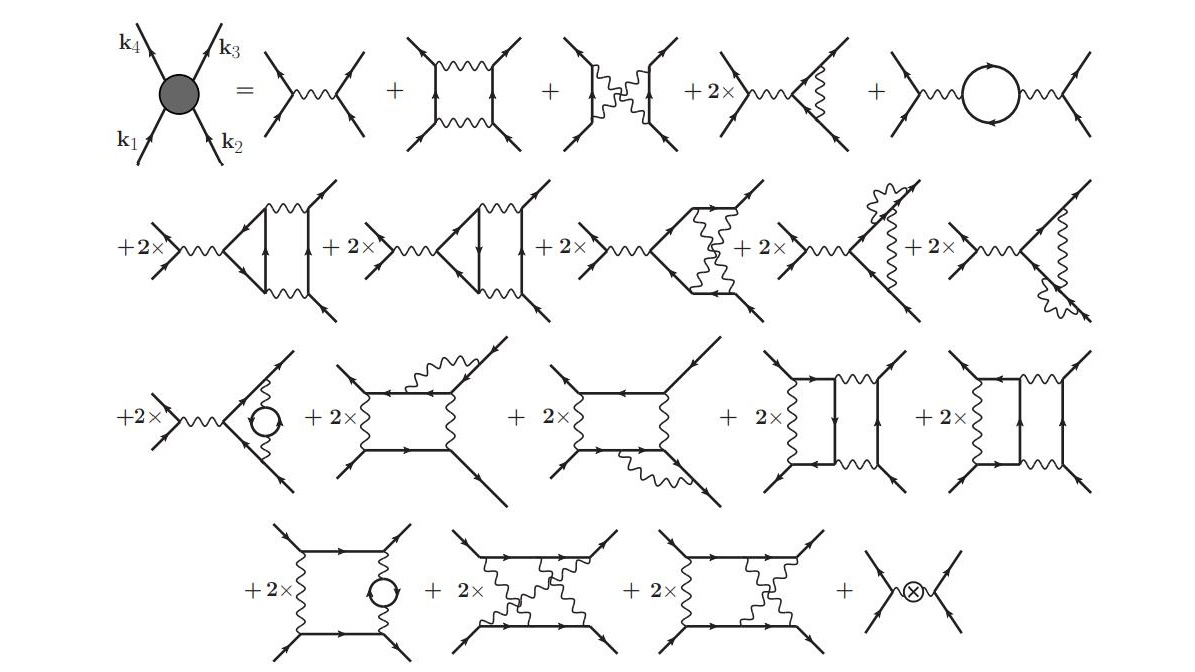

In physics, we often hear talk of a “final theory,” or a theory of everything. This would be a description of all the fundamental particles of nature and how they interact with one another, amounting to the complete picture of our subatomic reality. Is this a reasonable expectation or goal for fundamental science?

Such a theory, at least when it comes to subatomic physics, would correspond to the final map. There is a delicate balance here — one that is often hard to express when thinking about this issue. Of course, science should always be pushing its boundaries and expanding our knowledge base. We should and must always strive to create better maps of the world. But to believe that there is a final map is simply wrong, more intellectual vanity than science.

By its very nature, science can never reach a final state of knowledge in any discipline. Just as it is pretty much impossible to catalog all species of insects or fungi in the world, we can’t ever be sure that what we think is the final understanding of subatomic particles and their interactions is truly final.

In the case of bugs and fungi: It’s not just practically impossible to locate them all in the vastness of Earth’s surface, but also some species would go extinct during the survey, while others may undergo mutations and changes. There is an elusiveness to the whole enterprise, one that should both motivate and inspire a healthy dose of humility.

In the case of elementary particles, it’s always possible that some will escape our detectors and search algorithms. We can’t ever be sure that we have a net fine enough to capture all there is to capture in the subatomic world, for the simple reason that we can’t ever know all there is to capture!

A map is a device that serves a very precise purpose: to guide you from point A to point B. An efficient map is one that does its job of stripping out all the unnecessary details while still fulfilling its function. That’s what models do in science: They represent the essential aspects of reality we want to study, leaving out what’s not needed. There’s an economy in simplicity.

Thinking of science as the map and nature as the territory, Borges teaches us an important lesson. We should be proud of the maps we can make of the world and strive to perfect them. But we should also be aware that maps provide only limited information about the territory. We see the world through very human eyes, and our imperfect maps reflect this.