The world is hell, but life is a miracle

- How are we to carry on when the world seems to sink into darkness?

- Science and sacredness both remind us that we are part of a greater whole. Taking small moments to reflect on the vastness of life and being allows us to retain our wonder, even in difficult times.

- A sense of the sacred can also be the source of an endless resolve and a boundless hope.

Things seem to be sliding into darkness. The climate crisis deepens. The threat of a nuclear exchange has reappeared. And throughout the world, intense polarization is splitting peoples and nations apart. Every day the news reminds us that we are surrounded by anger, fear, and a rising dread that the future is going to be worse than the past.

How are we to live in the midst of such a world? How do we go about our lives, do our shopping, and care for our families, when it seems like so much is spinning apart? How do we find any hope and any simple joy in the middle of such strife and fear?

Like everyone else, I am staring down the barrel of these questions. Today, I want to offer an attempt at an answer, in the form of two terms: science and the sacred. I know these terms are not usually placed in the same sentence, and certainly not in this context. But their union can bring some sense to these troubled times.

The beauty of science in the hardest times

Every human being is born into their historical moment. We are given no choice in the matter. We might live in Tang Dynasty China in 700, the Iroquois Confederacy in 1500, or Czarist Russia in 1915. We all find ourselves in these particular situations with their sometimes impossible difficulties that must be faced. But how we deal with them day to day, moment to moment — that is where some freedom arises.

The beauty of science, or at least a scientific perspective, is that it takes the everyday and asks you to look just a little bit deeper, to reflect just a moment longer. Most of the time the flurry of, say, ants on the ground beneath your feet is invisible to you. But if you can take what the Buddhists call “the backward step” for a moment, you can pause your own busy comings-and-goings to take a real look at those creatures. You can see, maybe only briefly, that there are secret communications hiding behind their ceaseless motion. Something is going on there. It is something very old and very powerful, and it has nothing to do with your worries or the disasters of your times.

The whole world is like that.

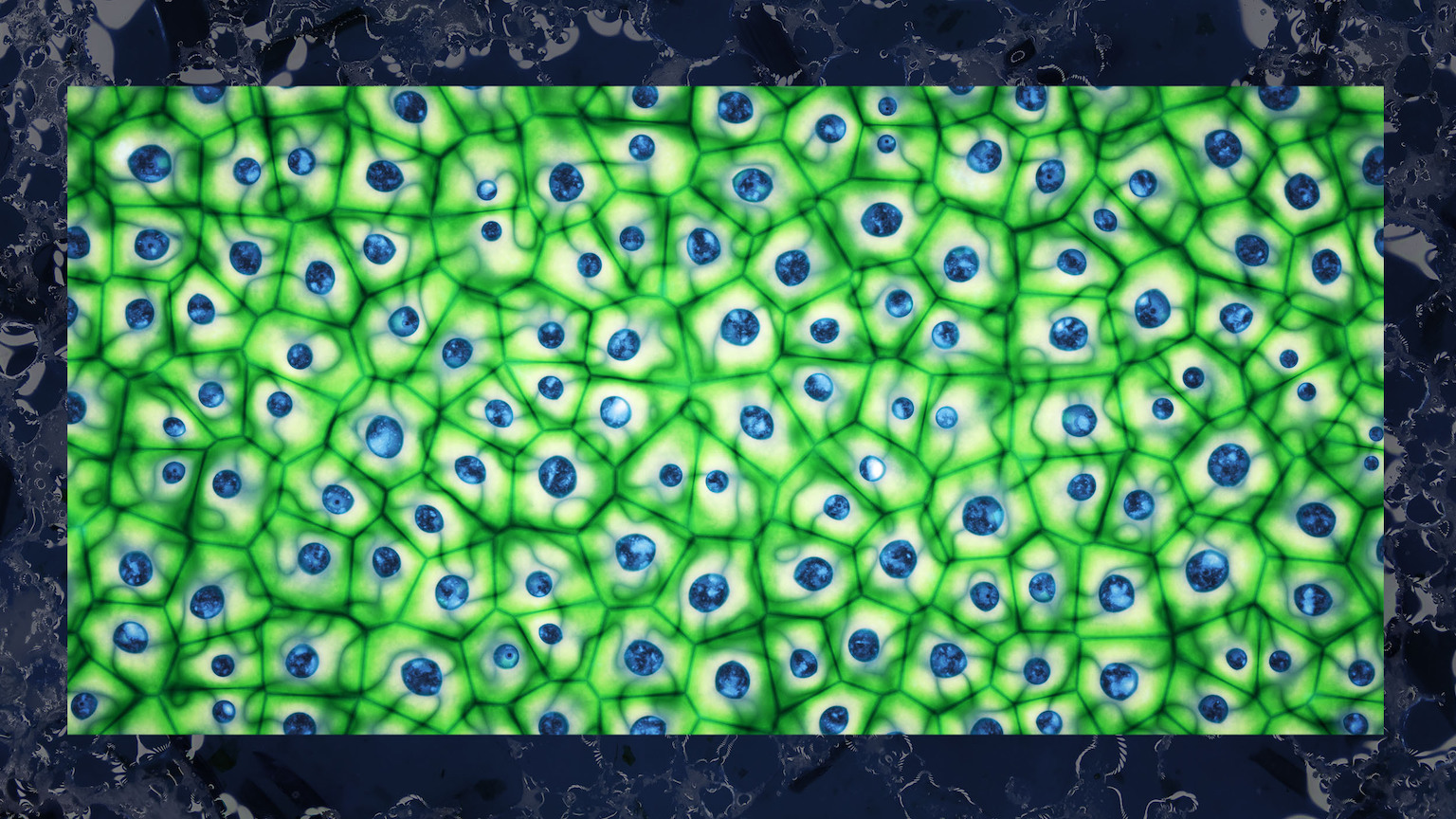

The stars whirling overhead at night, the chlorophyll in the green trees, the winds blowing from the west. Each one is a node in the vast, variegated, infinite network of life and being. What science offers is a way of looking at it all as a child would. Beginning with wonder and moving toward the understanding that all of it has its own purpose, we can get a wider view of the brief time we get to spend with the Universe.

I often think of the men and women who practiced the craft of scientific inquiry in other difficult times: the French Revolution, or the rise of Bolshevik terror. They too had to deal with uncertainty and fear. But by continuing to approach the world through curiosity and love, they gained some space and some peace. We can do the same when we hew close to our own wonder and curiosity.

A way of approaching experience

This brings us to the sacred. For me, the moments when I can see the world on its own, dropping the concerns of my life and unburdened by this fraught historical moment, are sacred. What is in that word, “sacred?” Is it about this particular scripture or that particular religion?

No.

As the scholar Marcia Eliade pointed out, “sacred” is a way of approaching experience. It goes back to the very roots of being human, to a time when our hunter-gatherer ancestors could feel the sense of more when they came on a bend in a river or stumbled across a mountain glade. The sacred is the opposite of the profane. It is the opposite of all those times when we are living in our heads, mulling over our worries, or focused on just trying to get by. Sacredness appears in those moments when life overflows its banks — when we see the vast, variegated, and infinite network of life and being we each are a part of.

To be clear, none of this changes the responsibility each of us has to be of service in difficult times. None of it diminishes the hardships we are all likely to face if the world continues to turn darker. What it can do is show us that those responsibilities and hardships play out on a much larger stage than our fears let us see. We are not the first, nor will we be the last, to face difficult times. The wonder and curiosity I am talking about, the sense of sacredness, is what has always carried people through. It is a reminder that this life — this chance to be here among stars and trees and mountains and rivers — is a kind of miracle. That sense of the sacred can also be the source of an endless resolve and a boundless hope, right in the midst of the disaster which is always also part of life.