James Webb Space Telescope finds possible signs of life chemistry on a strange world

- A new discovery by the James Webb Space Telescope found possible hints of a molecule which, at least on Earth, is associated with life.

- As usual, with such important discoveries, more observations are needed for validation.

- But even if the discovery is not validated, the data serves to confirm the remarkable power of the James Webb Space Telescope and promises to push forward our search for life in other worlds.

That Earth is unique we all know. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be here asking questions about other worlds. But nature never ceases to amaze, and recently the James Webb Space Telescope just confirmed once again that reality is stranger than fiction.

An exoplanet extravaganza

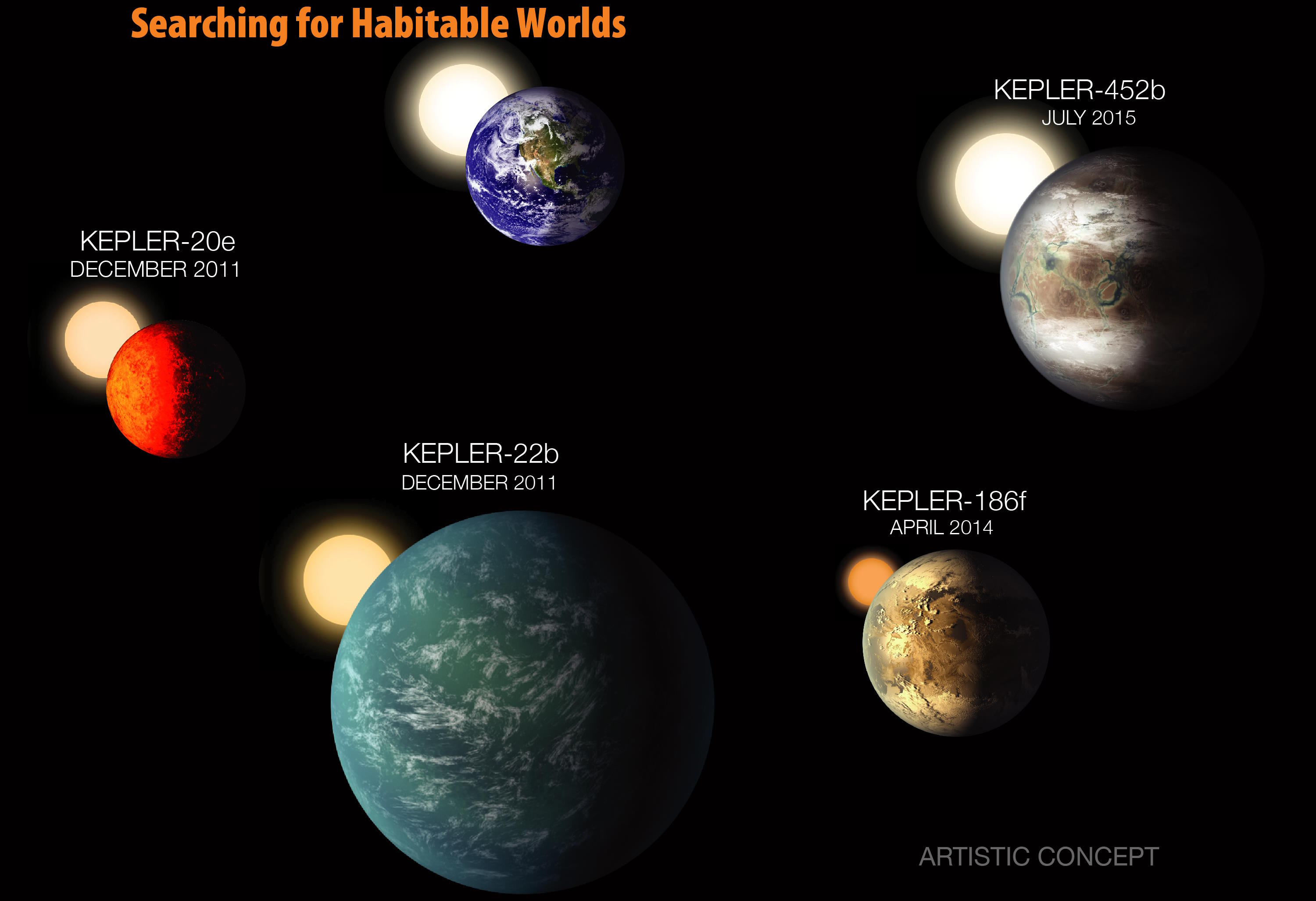

We now know that most stars have planets orbiting around them. As of today, we have confirmed the existence of 5,514 exoplanets in 4,107 planetary systems, with 928 systems having more than one planet. So roughly, 25% of stars host planetary systems containing 2+ planets and, quite possibly, with moons going around them.

These exoplanets are truly amazing, each different, each with its own composition and history. There are no two worlds exactly alike. Even when astronomers refer to “Earth-like” or “Neptune-like” planets, they mean worlds with masses and radii similar to Earth or Neptune, not duplicates of Earth or Neptune. Enormous variability ensues as planets form, which dictates their chemical composition, geological activity, and atmospheres. So, when discoveries point to worlds with chemicals related, even if superficially, to life, we pay attention.

K2-18 b

This week, NASA announced that the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) captured the atmospheric spectrum of planet K2-18 b with excellent precision. K2-18 b is a “sub-Neptune” planet — that is, a world with a mass about 8.9 times that of Earth but below that of Neptune, orbiting the cool dwarf star K2-18 (hence the planet’s name) located 120 light-years from Earth in the constellation Leo. Since our Solar System doesn’t have any sub-Neptune planets, this kind of world is poorly understood, even if it is the type most often found in exoplanet searches. Excitingly, K2-18 b orbits within its star’s habitable zone, implying that if there is water on its surface, it could be liquid. And the first guideline when looking for life in other worlds is “follow the water.”

The measured spectrum is good enough for scientists to identify chemical compounds that indicate active chemistry and, if the initial hints are confirmed, even the possibility of some biological activity. The main compounds that stand out in the spectrum are methane, carbon dioxide, and — the most interesting one — dimethyl sulfide, a compound that (at least on Earth) is only produced by life.

It is a familiar and stinky chemical, produced for example when cooking cabbage, beetroots, and seafood. It is also produced by marine phytoplankton. In fact, dimethyl sulfide is often called the “smell of the sea.” If you ever took a walk on a rocky shore during low tide, you know the smell. Also, and I am a fan, it is the main volatile chemical released by truffles, which pigs and dogs use to detect the delicious (and very expensive) fungi. Life is often smelly, including the good stuff.

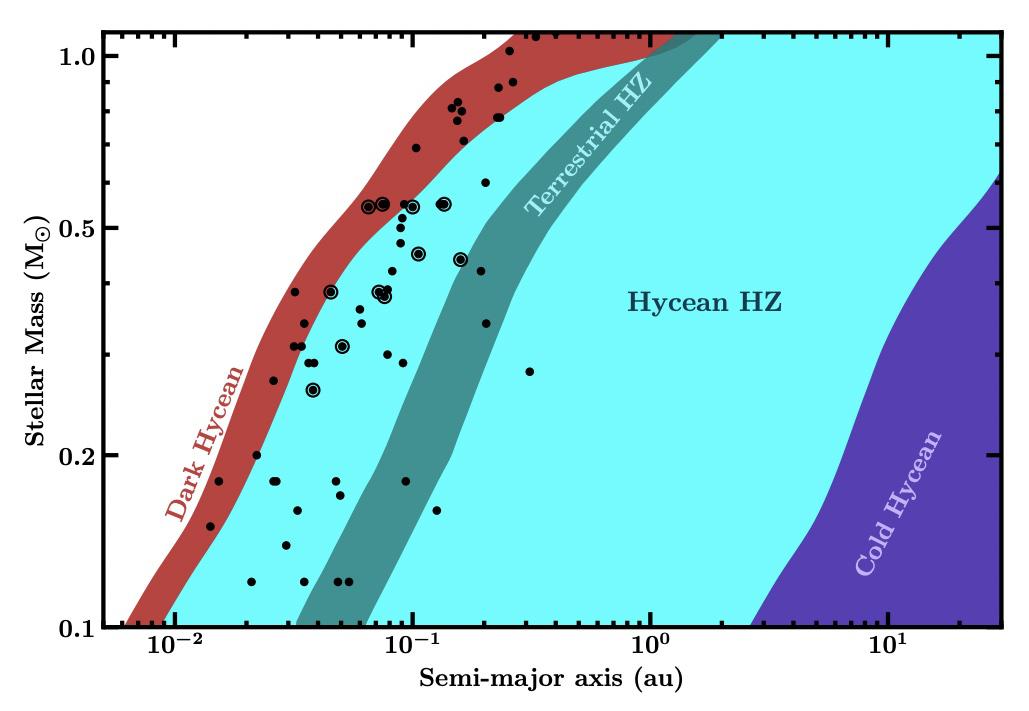

With the new spectrum and orbital information, scientists are exploring the possibility that K2-18 b could be a Hycean world, with an atmosphere that could be rich in hydrogen and a surface covered by an ocean of water. If all this is confirmed, the discovery would expand our search for life in other worlds to very exotic habitats, huge planets orbiting very close to small and cool stars.

Expect to be surprised

When dealing with potentially very exciting data such as this, scientists must be extra careful to draw conclusions. The signal from dimethyl sulfide is not very robust and will require further observations from Webb’s mid-infrared instrument for validation. Being very close to its parent star means the planet’s surface is likely subject to a high amount of radiation, which is often hostile to life. The ocean, if it exists, may be too hot to be habitable. But life as we know it here on Earth is resilient and creative. And even if no life out there will be as it is here, it’s a safe bet that if it exists elsewhere, it will also be resilient and creative. And it will, no doubt, surprise us in unexpected ways.