From astrology to astronomy, humans always look to the skies

- Since the earliest agrarian civilizations, humans have looked to the skies for answers. They believed the gods wrote our destiny in the stars and planets. That’s where astrology comes from.

- The urge to understand the skies only grew stronger as science evolved, even if the questions changed.

- Modern astronomy links the sacred skies of our ancestors with the human need to know our origins and our place in the Universe. The roots of science stretch all the way down to magical thinking.

Hundreds of millions of people read their horoscopes every day. Seekers scan the skies for answers to life’s challenges, believing that the planets, and their alignments relative to constellations, have something direct to say to each of us. Many still confuse astrology with astronomy. Even with all my scientific training, I cannot say that I blame them. Would it not be wonderful if the cosmos indeed spoke to us, acting as an oracle? If somehow it could help us find answers for life’s troubles and tribulations—answers coded in the arrangements of planets and stars?

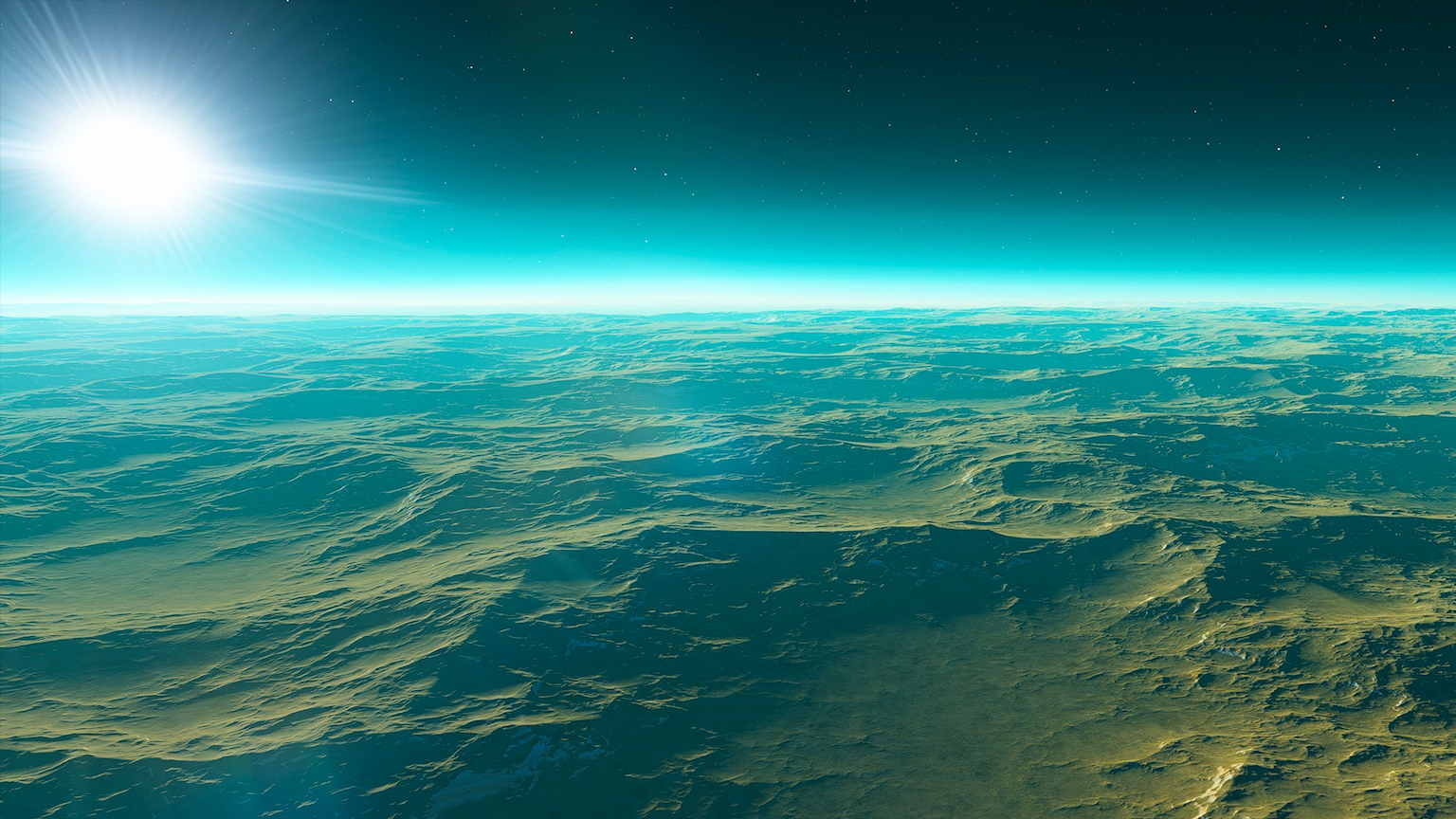

The better we know the heavens, the better we know ourselves. Even though modern science has stopped seeing the stars as an oracle, we still search for answers in the skies, albeit answers to different questions. As we study the skies scientifically, we are trying to explain our cosmic origins, the beginnings of life on Earth—and to know whether we are alone in the vastness of space.

An ancient, undying pursuit

This impulse is as old as civilization. We have been seeking the stars’ guidance at least since the earliest agricultural gatherings along the Tigris and the Euphrates Rivers, and probably before that. The Babylonians had a serious observational program. They mapped in great detail the motions of planets along the Zodiac—the belt about 8 degrees to either side of the ecliptic, and divided into 12 constellations. For example, the Venus Tablet of Ammisaduqa, dating from about the mid-17th century BCE, recorded the risings and settings of Venus for a period of 21 years. The main goal was astrological. The Babylonians tried to interpret the planet’s positions as omens for the king.

We have to wonder what inspires this prevalent and constant fascination with the skies. Why, from astrology to astronomy, does it endure?

In ancient times and for many indigenous cultures, the skies were (and still are) sacred. Countless religious narratives and mythical tales from across the planet attest to this. To know the skies was to have some level of control over the course of events that affected people, communities, and kingdoms. The gods wrote their messages on the dark canvas of the night sky, using the celestial luminaries as their ink. The shaman, the priest, the holy man or woman were the interpreters, the decoders. They could translate the will of the gods into a message the people could understand.

Fast forward to the 17th century CE, as Galileo and Kepler were establishing the roots of modern science and astronomy. To them the skies were still sacred, even if in different ways from their predecessors. Theirs was a Christian god, creator of the universe and everything in it. Galileo’s feud with the Inquisition was not one of the atheist versus the faithful, as it is often depicted. Instead, it was a struggle for power and control over the interpretation of the Scriptures.

From the astrology of old to astronomy

The urge to understand the skies, the motions of the planets, and the nature of the stars only grew stronger as science evolved.

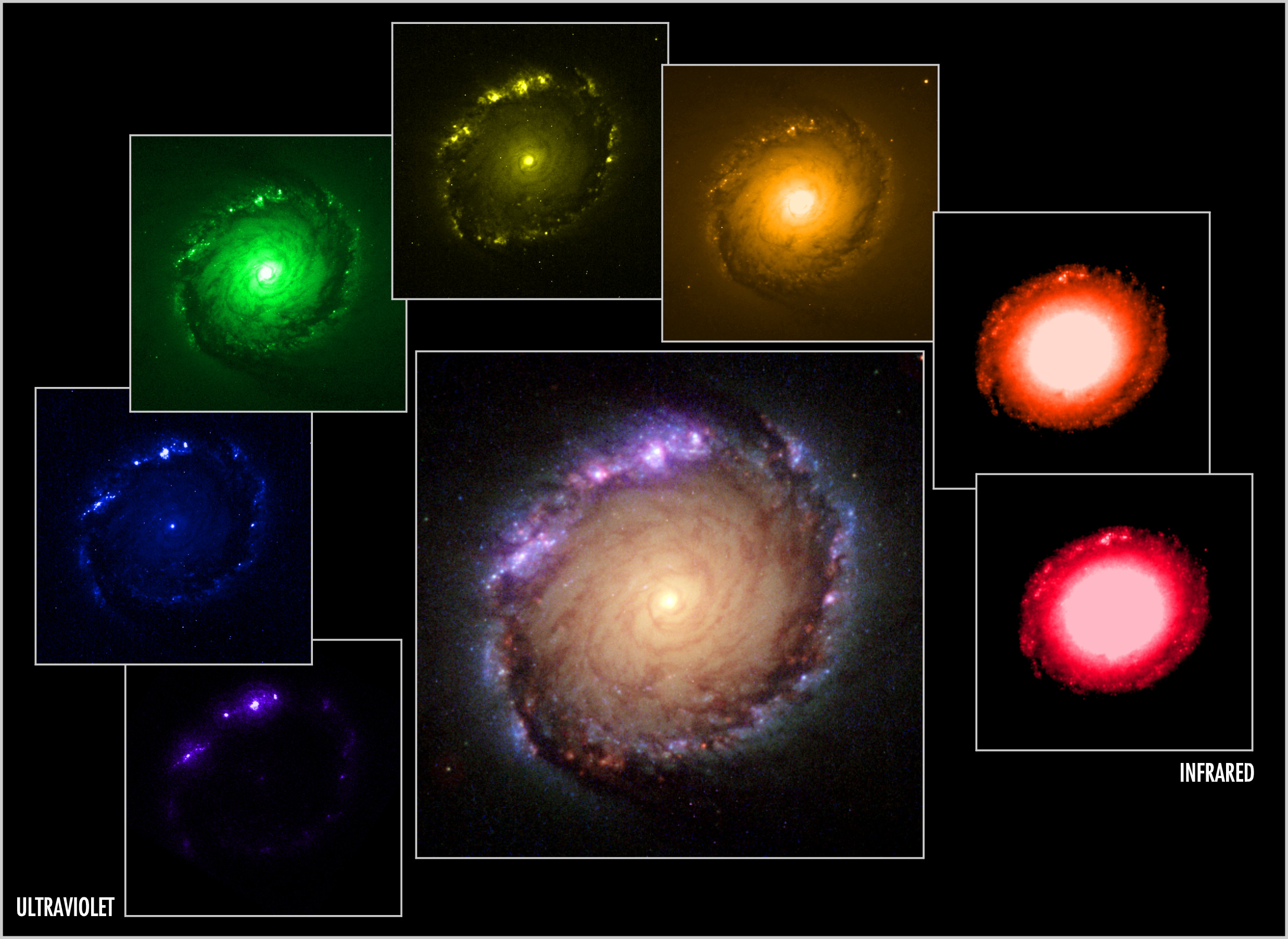

The stars may be way out there, distant and unreachable, yet we feel a deep connection to them. Walking through an open field on a clear, moonless night speaks to us on many different levels. In the modern scientific attempt to study the skies, we identify the same desire for meaning that drove our ancestors to look up and worship the gods. Our most advanced telescopes, such as the Very Large Telescope and the ALMA facility operated by the European Southern Observatory in Chile, or the cluster of amazing telescopes atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii, are testimonies of our modern urge to decipher the heavens. Now we add the spectacular James Webb Space Telescope and its promise to shed some light on many current mysteries of astronomy, including the origin of the first stars when the universe was still very young. We know the answers are there, waiting.

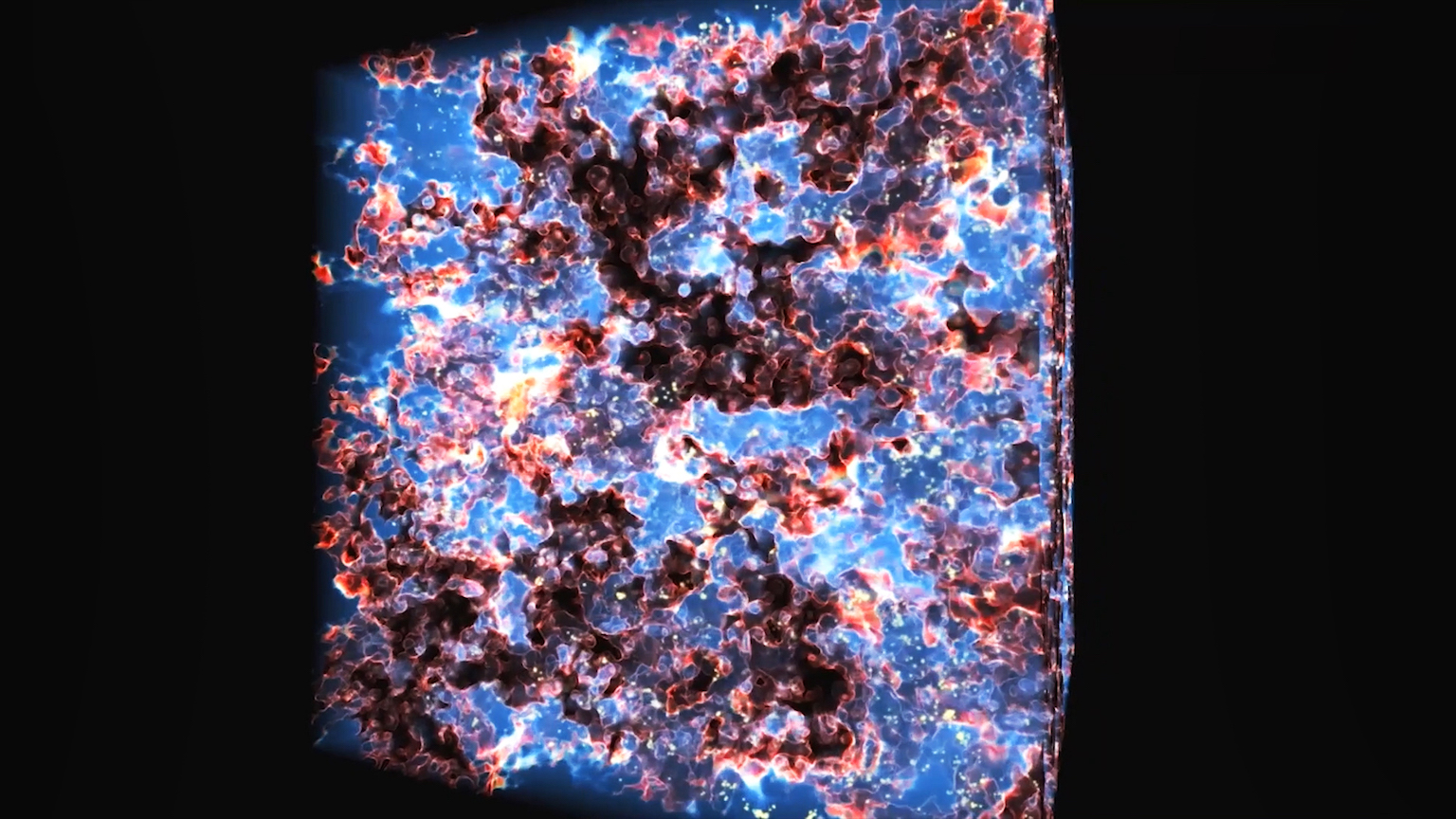

The circle closes when we realize that we ourselves are made of star stuff. The atoms that compose our bodies and everything around us came from stars that died more than five billion years ago. To know this—to know that we can trace our material origins to the cosmos—is to link our existence, our individual and collective history, to that of the universe. We have discovered that we are molecular machines made of star stuff that can ponder our origins and destiny. This is the worldview modern science has brought about, and it is nothing short of wonderful. It celebrates and gives meaning to our ancestors’ urge to decipher the skies. They were looking up to find their origin; we looked up and found it.