Aliens are a mirror to humanity

Credit: rolffimages / 341809797 via Adobe Stock

- Scientists explored the possibility of extraterrestrial life long before aliens became a fascination in popular culture.

- Aliens serve as a mirror to our species. They represent the creativity and promise — as well as the destruction and terror — of being human.

- Our conception of aliens can teach us about our fragility and the need to grow up as a species if we are to avoid one of the dystopian scenarios of our human-made alien tales.

Few topics are as fascinating to the human imagination as aliens. They are good, they are evil; they are divine, they are devilish; they are invasive, inspiring, advisors, predators. The strangeness that European explorers attributed to the creatures beyond the confines of (their) known world — exotic life forms that filled their cabinets of curiosities — has been expanded to the vastness of outer space. “Here be dragons,” became “There be aliens.”

Scientists were the first to imagine aliens

Even before Galileo pointed his telescope to the heavens to conclude that Earth was a mere planet like Mars or Jupiter, some dared to conceive of other worlds with other creatures, possibly human, possibly not. Giordano Bruno, in the late 1500s, proposed that stars are other suns, with planets circling around them, pregnant with creatures capable of sin or virtue, and hence in need of a savior like us. In 1608, Johannes Kepler wrote “Somnium” (Dream), a short story of an imaginary trip to the moon, where the traveler finds the most remarkable creatures, anticipating some of Darwin’s ideas of natural selection and adaptation. In Cosmotheoros, from 1698, Christian Huygens, one of the greatest scientists of the 17th century, wrote with confidence that the Mercurians, “tho they live so much nearer the Sun, the Fountain of Life and Vigour, are much more airy and ingenious than we.” The first to imagine aliens were not novelists or artists but scientists.

The big lesson here is that we are telling alien stories that could save us from ourselves if only we care to pay attention.

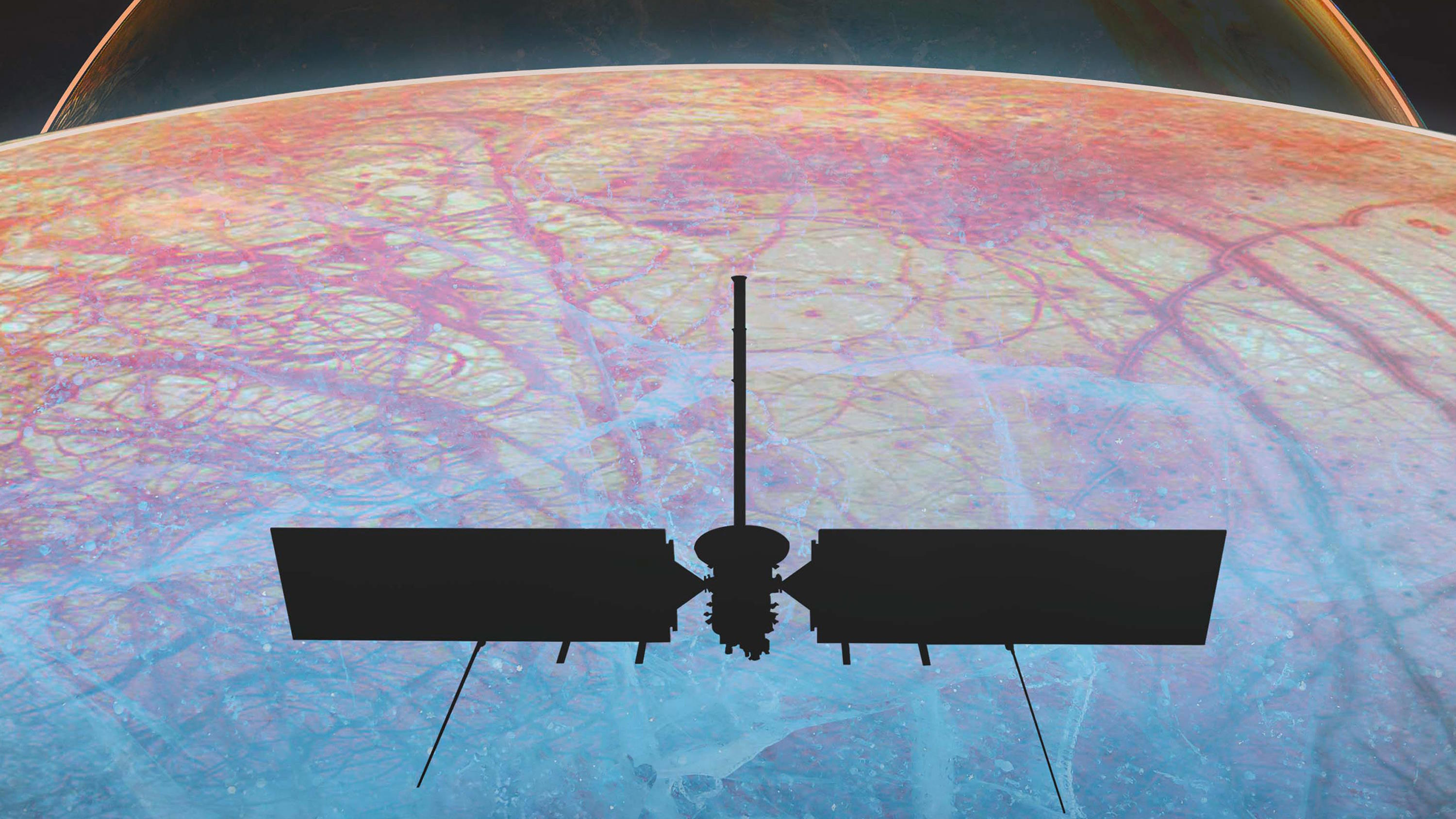

The expectation of finding alien life has only expanded since then, accelerated by spectacular advances in astronomy and space exploration, as we inch closer to finding answers to the question we all have — namely, whether we are the exception or the rule, whether we are alone or not. The excitement is palpable and often explosive in the media. In 1996, President Bill Clinton made a speech on the possible discovery of primitive life on Mars, albeit stressing that the potential discovery of a biosignature on the meteorite found in Antarctica still needed more serious scrutiny.

As I wrote two weeks ago, the interstellar traveler ‘Oumuamua has been deemed by serious scientists as a potential alien spying device, keen on figuring out details of the inner solar system, including us. As I explained, most of the scientific community denies that this is a valid conjecture. Not long ago, more excitement bubbled up about the possible discovery of phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus as a potential signal for biochemical activity. (Recent reanalysis decreased the strength of the signal but didn’t eliminate it.) However, attributing phosphine unequivocally to life is a very large step.

Aliens are a mirror on the human condition

Adding the countless books, movies, plays, short stories, and videocasts about extraterrestrial life, we see a coming together of scientific and popular culture that is quite rare in other disciplines. Only genetic engineering and artificial intelligence come close, although still a distant second and third place. Why? What is it about the possibility of life elsewhere that is so seductive to humans?

The portraits of aliens in fiction can help us, as can the earlier speculation of alien life from the scientific pioneers of the Renaissance. We have met the aliens, and they are us. They represent a mirror we use to see ourselves, the good and the evil of humanity, the utopian and dystopian views of our future. As we speculate about what they could be — and I’m here referring mostly to intelligent life forms, not the much more likely microbial life forms — we see a projection of the promise and perils of having self-awareness and a capacity to build technologies that can enhance and destroy life as we know it. Aliens are a sort of moral compass of the scientific age, their existence and fate serving as something like rehearsals of what could become of us.

Aliens also relate directly to the state of our scientific knowledge, often pushing the boundaries of what is possible. In what became known as Arthur C. Clarke’s Third Law — that is, “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” — aliens represent what could become the norm in our future. I think of my father’s puzzlement looking at a VCR in the 1970s and see my teenage son’s disdain as he watches me puzzling over the explosion of social media platforms. “Who needs yet another one?” “You really don’t get it dad, do you?” Aliens have the inventions of tomorrow, and for that, they serve to push our collective imagination to catch up with them. Or not, if they represent a dystopian future.

In War of the Worlds, H.G. Wells used the latest biological science, natural selection, and the discovery that microbial pathogens transmit diseases, to both save us from very evil invaders that were dying of thirst on their home planet and to show how our inventions were pitiful in comparison with theirs. It is colonialism reversed: if colonialist Europeans killed countless natives by infecting them with diseases, in Wells’ novel, Mother Earth saved humanity using the same microbes on alien invaders. As the threat in the novel is from alien invaders to the whole of humankind, colonialism goes global. It’s them vs. us since we are all victims and vulnerable to their attack. Wells’ twist is brilliant: despite their technological superiority, the invaders were also vulnerable, without the immune defenses to protect themselves from our terrestrial bugs. You can’t fool nature.

The big lesson here is that we are telling alien stories that could save us from ourselves if only we care to pay attention, less by looking up to the skies and more by looking at each other.